Every year, millions of people worldwide face a silent but potentially deadly threat: blood clots forming in their veins. Imagine sitting at your desk during a long work shift or recovering from surgery when suddenly, a clot breaks free and travels to your lungs. This scenario represents Venous Thromboembolism (VTE), a condition that claims lives yet remains preventable and treatable when caught early. Whether you’re an MBBS student preparing for exams, a practicing physician seeking the latest guidelines, or someone concerned about personal risk factors, understanding VTE can literally be lifesaving.

Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) encompasses two interconnected conditions: Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) and Pulmonary Embolism (PE). Recent updates to VTE guidelines in 2024 have transformed how clinicians approach diagnosis and management, particularly regarding age-adjusted D-dimer testing and new oral anticoagulants. This comprehensive guide breaks down everything you need to know about VTE risk factors, diagnostic approaches including the Wells score (DVT / PE), the D-dimer test, imaging modalities, and cutting-edge VTE management strategies including mechanical thrombectomy for PE and perioperative anticoagulation management.

What is Venous Thromboembolism?

Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) refers to blood clots that form within the venous circulation system. According to standard medical literature followed worldwide, VTE represents the third most common cardiovascular disorder after myocardial infarction and stroke. The term encompasses two primary manifestations that exist on a continuum of the same disease process.

Understanding Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT)

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) occurs when a blood clot (thrombus) forms in one or more deep veins of the body, most commonly in the legs. The clot partially or completely blocks blood flow through the vein, causing pain, swelling, and warmth in the affected area. Not all DVTs cause symptoms, which makes this condition particularly dangerous. When symptoms do appear, they typically include leg pain or tenderness (often starting in the calf), swelling in the affected leg, warm skin, and visible surface veins.

Understanding Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

Pulmonary Embolism (PE) represents a life-threatening complication when a clot from DVT breaks free (embolizes) and travels through the bloodstream to the lungs, blocking one or more pulmonary arteries. This obstruction prevents oxygen-rich blood from reaching lung tissue, potentially causing permanent lung damage, low oxygen levels, and damage to other organs. Massive PE can cause sudden cardiac arrest and death. Symptoms include sudden shortness of breath, chest pain that worsens with deep breathing, rapid heart rate, cough (sometimes with bloody sputum), and lightheadedness or fainting.

The relationship between Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) and Pulmonary Embolism (PE) is critical: approximately 50% of patients with proximal DVT have asymptomatic PE, and nearly 70% of patients with PE have evidence of DVT when carefully examined.

Why Venous Thromboembolism Matters

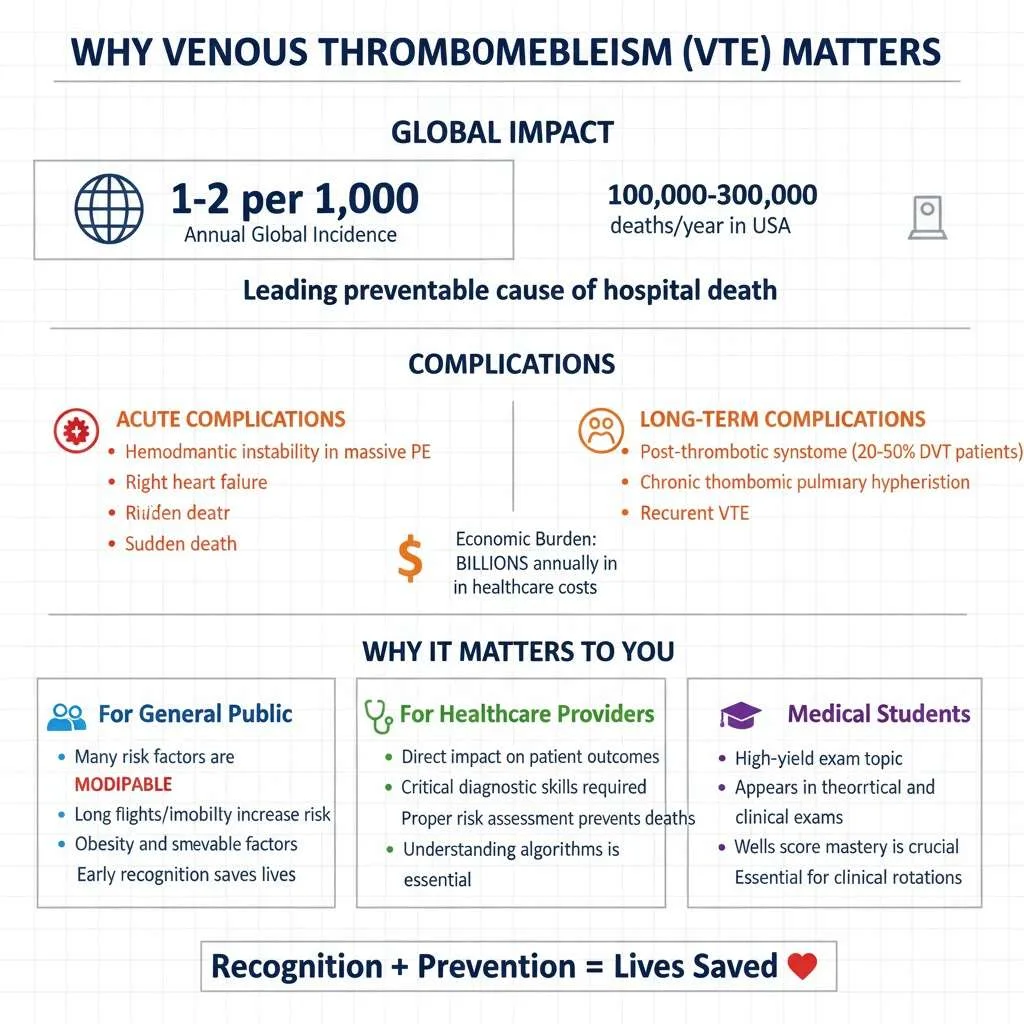

The clinical significance of Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) extends far beyond immediate health risks. Globally, VTE affects 1-2 per 1,000 individuals annually, with incidence increasing dramatically with age. In the United States alone, VTE causes an estimated 100,000-300,000 deaths each year, making it a leading preventable cause of hospital death. For medical students and healthcare providers, recognizing VTE risk factors and understanding diagnostic algorithms directly impacts patient outcomes.

Venous thromboembolism carries both acute and long-term consequences. Acute complications include hemodynamic instability in massive PE, right heart failure, and sudden death. Long-term complications encompass post-thrombotic syndrome (affecting 20-50% of DVT patients), chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension, and recurrent VTE. The economic burden is equally staggering, with annual costs exceeding billions in healthcare expenditure for diagnosis, treatment, and complications management.

For the general public, understanding VTE matters because many risk factors are modifiable. Prolonged immobility during long flights or car rides, obesity, smoking, and use of certain medications all increase risk. Awareness enables individuals to take preventive measures such as staying mobile, maintaining healthy weight, and recognizing warning signs requiring immediate medical attention.

For students preparing for medical exams, VTE represents a high-yield topic appearing frequently in both theoretical and clinical examinations. Mastering the diagnostic approach, particularly the Wells score (DVT / PE) and D-dimer test interpretation, is essential for clinical rotations and standardized assessments.

Read More : Management of Shock: Types, Clinical Assessment, and Latest Guidelines in Resuscitation

VTE Risk Factors: Who Is at Greatest Danger?

Understanding Venous Thromboembolism risk factors forms the cornerstone of prevention and early detection. Risk factors fall into inherited (thrombophilias), acquired, and provoked categories, with many patients having multiple simultaneous risk factors that compound their overall risk.

Patient-Specific Risk Factors

Inherited Risk Factors:

- Factor V Leiden mutation (most common hereditary thrombophilia)

- Prothrombin G20210A gene mutation

- Protein C, Protein S, or Antithrombin deficiency

- Elevated Factor VIII levels

- Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome

Acquired Risk Factors:

- Age: Risk doubles with each decade after age 40

- Obesity: BMI >30 kg/m² increases risk 2-3 fold

- Previous VTE: History of VTE increases recurrence risk by 10-30%

- Cancer: Active malignancy increases risk 4-7 fold, particularly pancreatic, lung, brain, and hematologic cancers

- Pregnancy and postpartum period: Risk increases 5-fold during pregnancy and 20-fold in the first 6 weeks postpartum

- Hormone therapy: Oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy increase risk 2-6 fold

- Immobilization: Prolonged bed rest, paralysis, or long-distance travel (>4 hours)

- Smoking: Increases risk by 1.5-2 fold

- Chronic medical conditions: Heart failure, inflammatory bowel disease, nephrotic syndrome, myeloproliferative disorders

Surgery and Orthopedic Surgery Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis

Surgical procedures dramatically elevate VTE risk, with rates varying by procedure type, duration, and patient characteristics. Without prophylaxis, general surgery carries 15-30% DVT risk, while major orthopedic procedures carry 40-60% risk.

Orthopedic surgery VTE prophylaxis has received particular attention in updated guidelines. Total hip replacement (THR) and total knee replacement (TKR) represent highest-risk procedures. The 2024 updates recommend:

- Pharmacological prophylaxis: Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), fondaparinux, direct oral anticoagulants (rivaroxaban, apixaban, dabigatran), or aspirin

- Mechanical prophylaxis: Intermittent pneumatic compression devices, graduated compression stockings

- Duration: Minimum 10-14 days, extended to 35 days for hip replacement

- Timing: LMWH starting 12+ hours pre-operatively or post-operatively, avoiding 4-hour peri-operative window

For trauma patients and non-ambulatory orthopedic surgery, risk assessment using validated tools guides individualized prophylaxis strategies.

How Venous Thromboembolism Happens

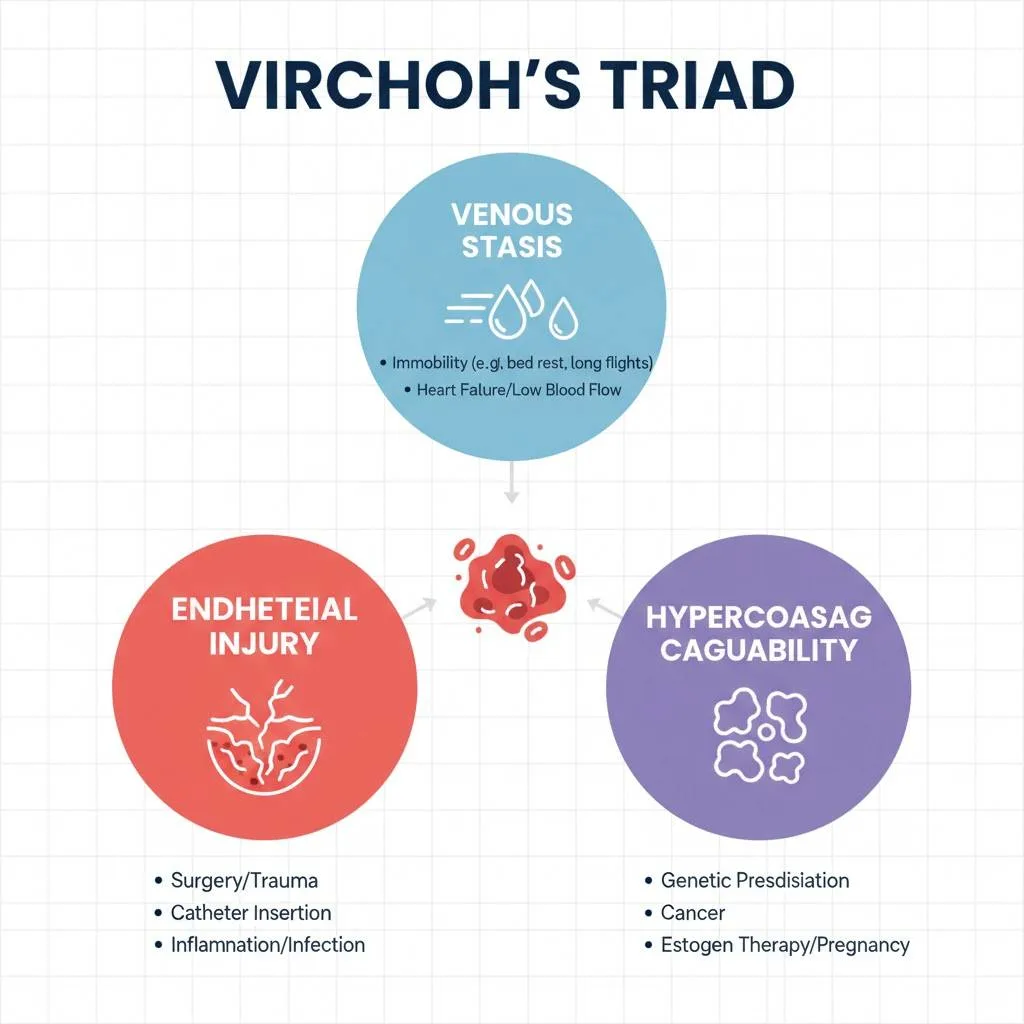

Understanding how Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) develops requires grasping Virchow’s Triad—the three fundamental conditions promoting clot formation: venous stasis (slow blood flow), endothelial injury (blood vessel damage), and hypercoagulability (increased clotting tendency).

Step 1: Venous Stasis

When blood flow slows in veins (during prolonged sitting, bed rest, or after surgery), blood cells and clotting factors accumulate instead of flowing smoothly. This pooling creates a favorable environment for clot formation. Unlike arteries with high-pressure, fast-flowing blood, veins rely on muscle contractions and one-way valves to push blood back to the heart. When this pumping mechanism fails, stasis occurs.

Step 2: Endothelial Injury

The endothelium (inner lining of blood vessels) normally prevents clotting by releasing anti-clotting substances. Trauma, surgery, inflammation, or chemical injury damages this protective layer, exposing subendothelial collagen. This exposure triggers platelet adhesion and activation of the coagulation cascade—the body’s clotting mechanism.

Step 3: Hypercoagulability

Various conditions shift the balance toward excessive clotting. Cancer cells release procoagulant substances, pregnancy increases clotting factor levels, genetic mutations impair natural anticoagulants, and inflammatory conditions activate the coagulation system. This hypercoagulable state primes the blood to clot more readily than normal.

Step 4: Thrombus Formation

When all three conditions converge, the coagulation cascade activates, converting fibrinogen to fibrin strands that trap red blood cells, forming a solid clot. Initially, this thrombus remains attached to the vessel wall. Over hours to days, it may propagate (grow) proximally in the vein.

Step 5: Embolization

The most dangerous complication occurs when part or all of the thrombus detaches from the vein wall, becoming an embolus. This free-floating clot travels through progressively larger veins, through the right heart chambers, and into pulmonary arteries. Lodging in lung vessels creates Pulmonary Embolism (PE), blocking blood flow to lung tissue.

VTE Diagnosis: Wells Score, D-dimer, and Imaging

Accurate Venous Thromboembolism diagnosis requires a systematic approach combining clinical assessment, laboratory testing, and imaging. Modern diagnostic algorithms emphasize risk stratification to avoid unnecessary testing while ensuring high sensitivity for detecting true VTE.

Wells Score (DVT / PE): Clinical Prediction Rules

The Wells score (DVT / PE) represents validated clinical prediction rules that estimate pre-test probability of VTE based on clinical findings. These tools guide whether to proceed with D-dimer testing or imaging directly.

Wells Score for DVT:

| Clinical Feature | Points |

|---|---|

| Active cancer (treatment within 6 months or palliative) | +1 |

| Paralysis, paresis, or recent leg immobilization/cast | +1 |

| Recently bedridden >3 days or major surgery within 4 weeks | +1 |

| Localized tenderness along deep venous system | +1 |

| Entire leg swollen | +1 |

| Calf swelling >3 cm compared to other leg (measured 10 cm below tibial tuberosity) | +1 |

| Pitting edema (greater in symptomatic leg) | +1 |

| Collateral superficial veins (non-varicose) | +1 |

| Previous documented DVT | +1 |

| Alternative diagnosis at least as likely as DVT | -2 |

Interpretation:

- Score ≤0: Low probability (3% DVT prevalence)

- Score 1-2: Moderate probability (17% DVT prevalence)

- Score ≥3: High probability (75% DVT prevalence)

Wells Score for PE:

| Clinical Feature | Points |

|---|---|

| Clinical signs/symptoms of DVT | +3 |

| PE is the #1 diagnosis or equally likely | +3 |

| Heart rate >100 bpm | +1.5 |

| Immobilization ≥3 days or surgery within 4 weeks | +1.5 |

| Previous objectively diagnosed PE or DVT | +1.5 |

| Hemoptysis | +1 |

| Malignancy (treatment within 6 months or palliative) | +1 |

Interpretation (Two-Level):

- PE unlikely: Score ≤4

- PE likely: Score >4

The Wells score (DVT / PE) demonstrates excellent utility in trauma patients and general populations, with studies confirming strong correlation between higher scores and increased VTE risk. Importantly, the Wells criteria help clinicians avoid unnecessary testing in low-probability patients while ensuring appropriate evaluation in higher-risk individuals.

D-dimer Test: Standard vs Age-Adjusted D-dimer

The D-dimer test measures fibrin degradation products in blood, elevated when clots form and break down. As a highly sensitive but non-specific test, D-dimer excels at ruling out VTE when negative but cannot confirm VTE when positive (elevated in many conditions including infection, inflammation, pregnancy, malignancy, and recent surgery).

Standard D-dimer Testing:

Traditional cutoff values use 500 μg/L (or 500 ng/mL depending on assay). Negative D-dimer (<500 μg/L) combined with low clinical probability safely excludes VTE without imaging in approximately 30% of patients.

Age-Adjusted D-dimer:

Research demonstrates D-dimer naturally increases with age, causing decreased specificity (more false positives) in older patients. Specificity drops from 49-67% in patients ≤50 years to 0-18% in patients ≥80 years using standard cutoffs. This means many elderly patients undergo unnecessary imaging.

Age-adjusted D-dimer applies the formula: Age × 10 μg/L for patients over 50 years. For example:

- 60-year-old: cutoff = 600 μg/L

- 75-year-old: cutoff = 750 μg/L

- 85-year-old: cutoff = 850 μg/L

Studies validate that age-adjusted D-dimer increases specificity (44% vs 27% with standard cutoff) while maintaining safety, with only marginal reduction in sensitivity (91% vs 96%). This approach allows safe exclusion of VTE in an additional 10-15% of older patients, reducing unnecessary imaging, radiation exposure, and healthcare costs.

High-sensitivity D-dimer assays further improve diagnostic accuracy, detecting lower D-dimer levels with enhanced sensitivity for VTE detection.

Recommended Diagnostic Algorithm:

- Calculate Wells score

- If low probability + negative age-adjusted D-dimer → VTE excluded, no imaging needed

- If moderate/high probability OR positive D-dimer → proceed to imaging

Imaging: Ultrasound, CT Pulmonary Angiography

When clinical probability or D-dimer indicates further evaluation, imaging confirms or excludes VTE diagnosis.

For DVT Diagnosis:

- Compression ultrasound (CUS): First-line imaging for suspected Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT)

- Technique: Transducer applies pressure over veins; normal veins compress completely, thrombosed veins remain non-compressible

- Accuracy: 95% sensitive and specific for proximal DVT, less sensitive for calf DVT

- Advantages: Non-invasive, no radiation, bedside availability

- Limitations: Operator-dependent, difficult in edematous legs, reduced sensitivity for isolated calf DVT

For PE Diagnosis:

- CT Pulmonary Angiography (CTPA): Gold standard for Pulmonary Embolism (PE) diagnosis

- Technique: IV contrast highlights pulmonary arteries; clots appear as filling defects

- Accuracy: >90% sensitivity and specificity

- Advantages: Rapid, widely available, visualizes alternative diagnoses

- Limitations: Radiation exposure, contrast contraindications (renal dysfunction, allergy)

- Ventilation-Perfusion (V/Q) scan: Alternative when CTPA contraindicated

- Technique: Assesses ventilation and blood flow matching in lungs

- Interpretation: Clots cause perfusion defects with normal ventilation

- Advantages: Less radiation than CTPA, no contrast needed

- Limitations: Non-diagnostic in 20-30% of cases, less available

VTE Management: From Acute Treatment to Long-Term Care

Modern Venous Thromboembolism management emphasizes prompt anticoagulation, risk stratification for complications, and appropriate duration of therapy. The 2024 VTE guidelines updates have refined recommendations for anticoagulant selection, dosing, and duration.

Anticoagulation: VTE Guidelines Updates 2024

Anticoagulation prevents clot propagation, allows natural fibrinolysis to dissolve existing clots, and prevents recurrence. Treatment phases include acute (first 5-10 days), primary (first 3 months), and extended (beyond 3 months) therapy.

Initial Anticoagulation Options:

-

Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH): Subcutaneous injections (enoxaparin, dalteparin)

-

Advantages: Predictable pharmacokinetics, no monitoring required, outpatient treatment

-

Dosing: Weight-based (e.g., enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice daily)

-

-

Unfractionated Heparin (UFH): Intravenous infusion

-

Advantages: Rapid onset/offset, reversible with protamine, renal safety

-

Monitoring: Requires aPTT monitoring

-

Indications: Severe renal failure, high bleeding risk requiring rapid reversal

-

-

Fondaparinux: Subcutaneous Factor Xa inhibitor

-

Advantages: Once-daily dosing, no monitoring

-

Weight-based dosing: <50 kg (5 mg), 50-100 kg (7.5 mg), >100 kg (10 mg)

-

New Oral Anticoagulants (NOACs/DOACs)

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), also called novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs), have revolutionized Venous Thromboembolism management. These medications target specific coagulation factors without requiring monitoring.

Available DOACs for VTE:

Factor Xa Inhibitors:

- Rivaroxaban: 15 mg twice daily for 21 days, then 20 mg once daily

- Apixaban: 10 mg twice daily for 7 days, then 5 mg twice daily

- Edoxaban: Requires 5 days LMWH/UFH lead-in, then 60 mg once daily

Direct Thrombin Inhibitor:

-

Dabigatran: Requires 5 days LMWH/UFH lead-in, then 150 mg twice daily

Advantages of DOACs over Warfarin:

- Fixed dosing without monitoring (no INR checks)

- Rapid onset (hours vs days for warfarin)

- Predictable pharmacokinetics

- Fewer drug-food interactions

- Lower intracranial bleeding risk

- Similar efficacy to warfarin

Network meta-analysis demonstrates NOACs reduce VTE recurrence compared to placebo and show comparable efficacy to warfarin, with favorable bleeding profiles. The 2024 guidelines recommend DOACs as first-line therapy for most VTE patients without contraindications.

DOAC Contraindications:

- Severe renal dysfunction (CrCl <30 mL/min for most DOACs)

- Antiphospholipid syndrome (warfarin preferred)

- Mechanical heart valves

- Gastrointestinal malignancies (increased bleeding risk)

- Pregnancy/breastfeeding

Mechanical Thrombectomy for PE

Mechanical thrombectomy for PE represents an advanced intervention for high-risk patients who cannot receive or fail thrombolysis. This catheter-based technique physically removes clots from pulmonary arteries.

Indications for mechanical thrombectomy:

- Hemodynamically unstable massive PE with contraindications to thrombolysis

- Failed thrombolytic therapy

- Cardiac arrest from PE

- Right ventricular dysfunction with clinical deterioration

Recent advances include VA-ECMO (veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) assisted percutaneous mechanical thrombectomy, which provides hemodynamic support during the procedure. Multi-center studies demonstrate:

- 100% technical success rate

- 72.7% survival beyond 90 days

- Rapid improvement in pulmonary hemodynamics

- Reduced right ventricle/left ventricle ratio

- Decreased pulmonary artery pressure

Mechanical thrombectomy for PE provides crucial treatment for up to 50% of PE patients contraindicated for thrombolytics due to recent surgery, bleeding risks, or stroke history. This intervention bridges the gap between anticoagulation alone (insufficient for high-risk PE) and systemic thrombolysis (too dangerous for many patients).

Perioperative Anticoagulation Management

Perioperative anticoagulation management presents challenges balancing VTE prevention against surgical bleeding risks. The 2024 guidelines provide detailed recommendations for patients on anticoagulation requiring surgery.

For Patients on DOACs:

- Low bleeding risk surgery: Hold DOAC 1-2 days before (based on renal function)

- High bleeding risk surgery: Hold DOAC 2-4 days before (longer with renal impairment)

- Restart timing: 1-3 days post-operatively when hemostasis achieved

- No bridging needed: DOACs have rapid offset/onset, eliminating heparin bridging

For Patients on Warfarin:

- Stop warfarin: 5 days pre-operatively

- Bridge therapy: High VTE risk patients receive LMWH during warfarin interruption

- Resume warfarin: Evening of or day after surgery

- Continue bridge: Until INR therapeutic (≥2.0)

VTE Prophylaxis Post-Operatively:

As discussed in orthopedic surgery VTE prophylaxis, mechanical and pharmacological prophylaxis should resume as soon as bleeding risk permits, typically 12-24 hours post-operatively.

Read More : Complete Blood Count Interpretation: Red Flags, Clinical Correlates & Exam Caselets

Comparing VTE Treatment Options

| Feature | Warfarin | LMWH | DOACs (Rivaroxaban/Apixaban/Edoxaban/Dabigatran) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Route | Oral | Subcutaneous injection | Oral |

| Monitoring | Required (INR 2-3) | None | None |

| Onset | 3-5 days (requires bridge) | Immediate | 1-4 hours |

| Offset | 3-5 days | 12-24 hours | 12-24 hours |

| Dosing | Daily, adjusted to INR | 1-2 times daily, weight-based | Fixed dosing |

| Drug Interactions | Many (food, medications) | Few | Moderate |

| Renal Adjustment | No | Yes (avoid if severe) | Yes (contraindicated if CrCl <30) |

| Reversal Agent | Vitamin K, PCC | Protamine (partial) | Idarucizumab (dabigatran), Andexanet (Xa inhibitors) |

| Cost | Low | Moderate | High |

| Pregnancy Safety | Teratogenic (avoid) | Safe | Contraindicated |

| Cancer-Associated VTE | Alternative option | First-line | Emerging option (avoid GI cancers) |

Common Mistakes to Avoid in VTE Care

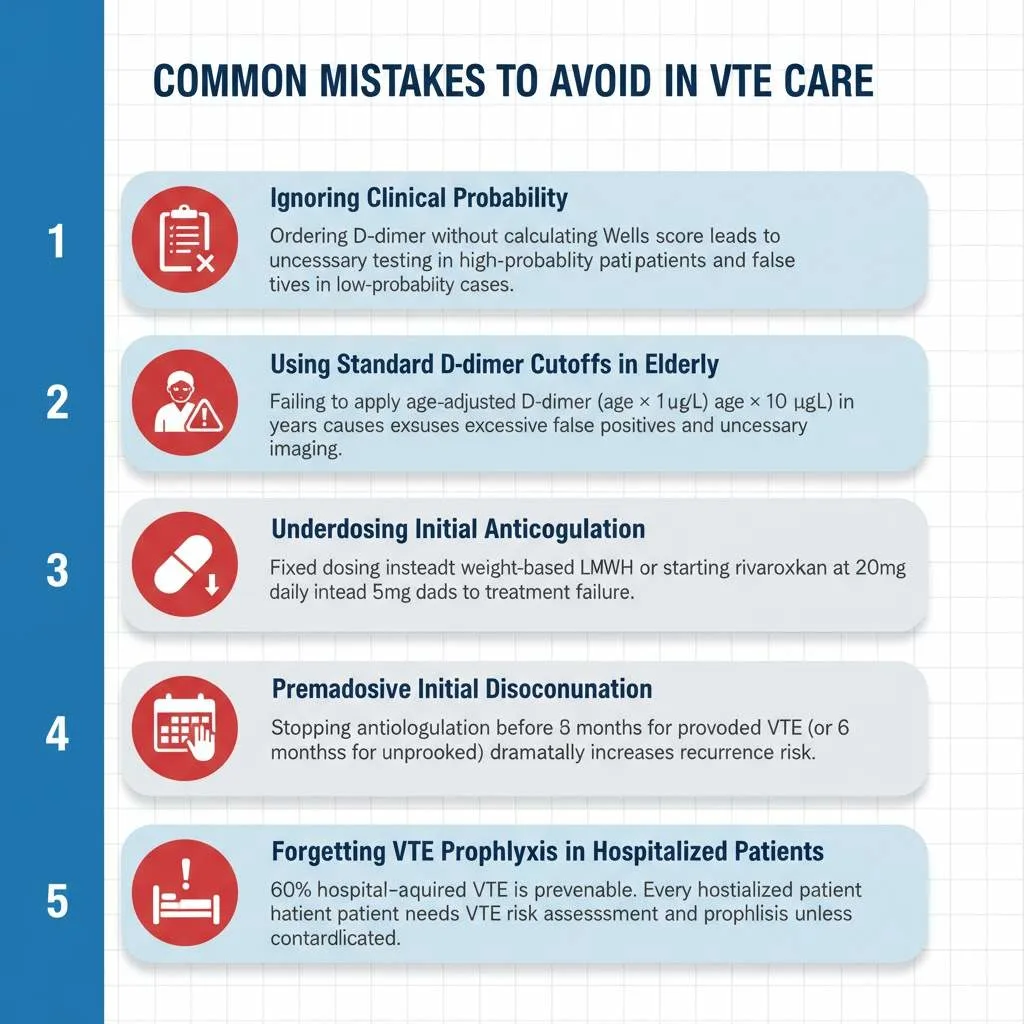

Mistake 1: Ignoring Clinical Probability

Many clinicians order D-dimer tests without first calculating the Wells score (DVT / PE). This approach leads to unnecessary testing in high-probability patients who need imaging regardless of D-dimer results, and false positives in patients with low clinical probability.

Mistake 2: Using Standard D-dimer Cutoffs in Elderly

Failing to apply age-adjusted D-dimer in patients over 50 years results in excessive false positives and unnecessary imaging. Remember: age × 10 μg/L formula significantly improves specificity while maintaining safety.

Mistake 3: Underdosing Initial Anticoagulation

Weight-based dosing is crucial for LMWH effectiveness. Using fixed doses or inadequate weight-based calculations leads to subtherapeutic anticoagulation and treatment failure. Similarly, using extended-duration dosing (e.g., rivaroxaban 20 mg) from day one instead of initial high-dose phase (15 mg twice daily) compromises outcomes.

Mistake 4: Premature Anticoagulation Discontinuation

VTE requires minimum 3 months anticoagulation for provoked events, longer for unprovoked events. Stopping therapy prematurely (after 4-6 weeks because symptoms resolved) dramatically increases recurrence risk.

Mistake 5: Forgetting VTE Prophylaxis in Hospitalized Patients

Up to 60% of hospital-acquired VTE cases are preventable through appropriate risk assessment and prophylaxis. Every hospitalized patient should receive VTE risk assessment and prophylaxis unless contraindicated.

Mistake 6: Inappropriate DOAC Use

Prescribing DOACs for antiphospholipid syndrome (warfarin superior), severe renal failure (accumulation risk), or GI malignancies (bleeding risk) contradicts evidence-based guidelines.

Mistake 7: Not Counseling About Warning Signs

Patients on anticoagulation need education about signs of recurrent VTE (leg swelling, chest pain, shortness of breath) and bleeding complications (unusual bruising, blood in urine/stool, severe headache). Failure to provide this education delays recognition of complications.

Frequently Asked Questions About Venous Thromboembolism (VTE)

Q : Can I prevent VTE during long flights?

A : Yes! During flights exceeding 4 hours, walk the aisle every 1-2 hours, perform calf exercises while seated (ankle pumps, knee lifts), stay hydrated, avoid alcohol, and consider wearing graduated compression stockings (15-20 mmHg). High-risk individuals should discuss prophylactic anticoagulation with their physician before travel.

Q : How long do I need to take blood thinners after VTE?

A : Treatment duration depends on VTE cause. Provoked VTE (after surgery, trauma, temporary risk factor) typically requires 3 months anticoagulation. Unprovoked VTE warrants 3-6 months minimum, with many patients continuing indefinitely due to high recurrence risk (10% per year after stopping). Your physician will assess bleeding risk versus recurrence risk to determine optimal duration.

Q : What is the difference between a D-dimer test and age-adjusted D-dimer?

A : Standard D-dimer test uses a fixed cutoff (500 μg/L) for all ages. Age-adjusted D-dimer uses the formula age × 10 μg/L for patients over 50, recognizing that D-dimer naturally increases with age. This adjustment reduces false positives in elderly patients, allowing VTE exclusion in 10-15% more older adults without imaging.

Q : Are blood clots hereditary?

A : Some thrombophilias (clotting disorders) are inherited, including Factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation, and deficiencies of natural anticoagulants (Protein C, Protein S, Antithrombin). However, most VTE cases result from acquired risk factors. Family history of VTE, especially in young relatives or unprovoked cases, warrants thrombophilia testing.

Q : Can I exercise with DVT?

A : After acute Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) diagnosis, activity restriction (bed rest) is no longer recommended. Modern evidence supports early mobilization once anticoagulation begins, as this does not increase PE risk and may reduce post-thrombotic syndrome. Start with gentle walking and gradually increase activity as symptoms improve. Avoid high-impact activities during acute phase.

Q : What foods should I avoid on blood thinners?

A : This depends on your anticoagulant. Warfarin requires consistent vitamin K intake (found in leafy greens); you don’t need to avoid these foods but should eat consistent amounts daily. DOACs have no dietary restrictions—a major advantage. All anticoagulants warrant caution with excessive alcohol, which increases bleeding risk.

Exam Questions & Answers: University Pattern

Question 1: Short Answer (5 Marks)

A 67-year-old male presents with left leg swelling and pain for 2 days. Calculate his Wells score for DVT given: active cancer treatment, entire leg swollen, calf 4 cm larger than right leg, pitting edema present, and no alternative diagnosis. What is your next diagnostic step?

Model Answer:

Wells Score Calculation:

- Active cancer treatment: +1

- Entire leg swollen: +1

- Calf >3 cm larger: +1

- Pitting edema: +1

- No alternative diagnosis: 0 (not -2)

- Total: 4 points = HIGH PROBABILITY

Next Diagnostic Step: With Wells score ≥3 (high probability), proceed directly to compression ultrasound imaging rather than D-dimer testing. D-dimer is unnecessary in high-probability cases as imaging is warranted regardless of D-dimer result. If ultrasound is negative but clinical suspicion remains high, consider serial ultrasound in 5-7 days or venography.

Mark Distribution: Wells calculation (2 marks), interpretation (1 mark), next step with rationale (2 marks)

Question 2: Long Answer (10 Marks)

Discuss the pathophysiology of Venous Thromboembolism using Virchow’s Triad. Explain how this understanding guides modern prophylaxis strategies, particularly in orthopedic surgery patients.

Model Answer:

Virchow’s Triad Components (4 marks):

1. Venous Stasis:

- Reduced blood flow velocity in veins creates opportunity for clot formation

- Occurs during immobilization, surgery, paralysis, or prolonged sitting

- Activation of clotting factors accumulate rather than being cleared

- Hypoxia of vessel walls due to sluggish flow

2. Endothelial Injury:

- Damage to protective inner vessel lining exposes subendothelial collagen

- Triggers platelet adhesion and activation

- Caused by trauma, surgery, inflammation, or chemical injury

- Loss of anticoagulant properties of healthy endothelium

3. Hypercoagulability:

- Increased tendency for blood to clot

- Genetic factors (Factor V Leiden, prothrombin mutation)

- Acquired factors (cancer, pregnancy, estrogen, inflammatory states)

- Imbalance favoring procoagulant over anticoagulant mechanisms

Modern Prophylaxis Strategies in Orthopedic Surgery (6 marks):

Addressing Venous Stasis:

- Early mobilization post-operatively

- Intermittent pneumatic compression devices

- Graduated compression stockings

- Active/passive leg exercises

Endothelial Injury:

- Minimally invasive surgical techniques

- Gentle tissue handling

- Prompt initiation of anticoagulation (12-24 hours post-op)

Addressing Hypercoagulability:

- Pharmacological prophylaxis (LMWH, DOACs, aspirin)

- Duration: 10-35 days depending on procedure

- Risk-stratified approach based on patient factors

Evidence-Based Protocols for Total Hip/Knee Replacement:

- LMWH (preferred), fondaparinux, rivaroxaban, apixaban, or dabigatran

- Mechanical + pharmacological prophylaxis (dual modality)

- Extended duration (minimum 10-14 days, up to 35 days for THR)

- Timing: Avoid 4-hour perioperative window for LMWH

Question 3: Case-Based MCQ (2 Marks)

A 78-year-old woman with suspected DVT has a Wells score of 1. Her D-dimer returns at 650 μg/L. What is the appropriate interpretation?

A) D-dimer positive; proceed to ultrasound

B) D-dimer negative using age-adjusted cutoff; DVT excluded

C) D-dimer equivocal; repeat in 24 hours

D) D-dimer positive; start anticoagulation immediately

Correct Answer: B

Explanation: Using age-adjusted D-dimer for this 78-year-old: cutoff = 78 × 10 = 780 μg/L. Her D-dimer of 650 μg/L is below the age-adjusted threshold, combined with low Wells score (1 = moderate probability), DVT can be safely excluded without ultrasound. Standard cutoff of 500 μg/L would generate a false positive, leading to unnecessary imaging. This demonstrates the clinical utility of age-adjusted D-dimer in elderly patients.

Question 4: Diagram Prompt & Viva Preparation

Draw and label a diagnostic algorithm for suspected Pulmonary Embolism incorporating Wells score and D-dimer testing.

Quick Diagram Prompt for Image Generation:

“Create a clinical flowchart diagram showing PE diagnostic algorithm: Start with ‘Suspected PE’ at top, branch to ‘Calculate Wells Score for PE’, then split into ‘PE Unlikely (≤4 points)’ and ‘PE Likely (>4 points)’. PE Unlikely branch leads to D-dimer test, splitting into ‘Negative – PE Excluded’ and ‘Positive – CTPA’. PE Likely branch goes directly to ‘CTPA’. Include decision nodes as diamonds, processes as rectangles, and outcomes as rounded rectangles. Use professional medical blue and white color scheme. Dimensions: 800x1000px.”

Viva Tips:

- Know Wells Criteria intimately: Examiners frequently ask you to calculate Wells scores on the spot

- Explain rationale: Always justify why you skip D-dimer in high-probability cases (positive result doesn’t change management)

- Discuss age-adjusted D-dimer: This demonstrates updated knowledge beyond basic curriculum

- Compare imaging modalities: Be ready to discuss why CTPA preferred over V/Q scan in most cases

- Risk stratification for PE: Understand hemodynamically stable vs unstable PE management differences

- DOAC specifics: Know which DOACs require lead-in therapy and renal dosing adjustments

Last-Minute Exam Checklist

Must-Know Facts:

- ✓ Wells DVT score ≥3 = high probability (75% prevalence)

- ✓ Wells PE score >4 = PE likely (two-level system)

- ✓ Age-adjusted D-dimer formula: Age × 10 μg/L for patients >50 years

- ✓ Standard D-dimer cutoff: 500 μg/L

- ✓ VTE prophylaxis duration post-THR: up to 35 days

- ✓ DOACs: Rivaroxaban and apixaban don’t need lead-in; edoxaban and dabigatran require 5 days LMWH/UFH first

- ✓ First-line imaging: Compression ultrasound for DVT, CTPA for PE

- ✓ Minimum anticoagulation duration: 3 months for provoked VTE

- ✓ Virchow’s Triad: Stasis, endothelial injury, hypercoagulability

- ✓ High-risk surgeries: Orthopedic (THR/TKR), major abdominal, cancer surgery

Common Exam Traps:

- Don’t forget the “-2 points” for alternative diagnosis in Wells DVT score

- Remember CTPA requires IV contrast (contraindicated in renal failure/allergy)

- DOACs contraindicated in pregnancy and severe renal failure

- Post-thrombotic syndrome is a long-term DVT complication, not an acute finding

- Warfarin is teratogenic but LMWH is safe in pregnancy

Conclusion: Taking Action Against Venous Thromboembolism

Venous Thromboembolism (VTE) represents a preventable yet potentially fatal condition affecting millions worldwide. Understanding VTE risk factors, recognizing warning signs, and applying evidence-based diagnostic approaches like the Wells score (DVT / PE) and age-adjusted D-dimer save lives daily in clinical practice. The 2024 VTE guidelines updates have refined VTE management strategies, particularly regarding DOAC use, mechanical thrombectomy for PE, and orthopedic surgery VTE prophylaxis, empowering clinicians to deliver optimal patient care.

For MBBS students, mastering VTE concepts ensures examination success and clinical competence. For practicing physicians, staying current with evolving guidelines and diagnostic strategies optimizes patient outcomes while reducing healthcare costs through appropriate testing.

At Simply MBBS, we’re committed to making complex medical topics accessible to everyone—from aspiring medical students to curious learners seeking reliable health information. We transform evidence-based medicine into clear, actionable knowledge that empowers better health decisions.

Ready to deepen your medical knowledge? Subscribe to our newsletter at simplymbbs.com for:

- Weekly medical topic breakdowns written for students and healthcare enthusiasts

- Exam-focused quick revision guides and mnemonics

- Latest guideline updates explained simply

- Clinical pearls that bridge classroom learning with real-world practice

- Exclusive study materials and visual infographics

Join thousands of medical students and healthcare professionals who trust Simply MBBS for accurate, engaging, and exam-relevant medical education. Whether you’re preparing for university exams, clinical rotations, or simply passionate about understanding how the human body works, our content meets you where you are and takes you where you want to go.

Don’t let complex medical topics overwhelm you. Visit simplymbbs.com today and transform your learning experience. Your journey to medical excellence starts with understanding one concept at a time—and we’re here to guide every step.