An unconscious patient represents one of the most critical emergencies in medical practice, demanding immediate assessment and life-saving interventions. Every year, emergency departments across the United States and India encounter thousands of cases where patients present with altered consciousness, ranging from drowsiness to deep coma. The ability to systematically approach an unconscious patient can mean the difference between life and death, permanent disability and full recovery.

Whether you are an MBBS student preparing for clinical rotations, a junior doctor handling night shifts, or a medical professional refreshing your emergency protocols, understanding the structured approach to unconscious patient management is essential for delivering optimal care.

What Is an Unconscious Patient?

An unconscious patient is defined as an individual experiencing significantly reduced alertness, diminished self-awareness, and impaired responsiveness to external stimuli. According to standard medical textbooks and the work of Plum and Posner, coma represents the most severe form of unconsciousness, characterized as “a state of unresponsiveness in which the patient lies with eyes closed and cannot be awakened to respond appropriately to stimuli, even with vigorous stimulation”.

Consciousness itself involves two critical components: arousal (wakefulness) and awareness (cognition). An unconscious state occurs when either or both of these elements become impaired due to dysfunction in the brain’s arousal systems. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 8 or below typically defines coma, while scores between 9-12 indicate moderate impairment of consciousness.

The anatomical basis of consciousness centers on the ascending reticular activating system (RASS), which originates in the upper pons and midbrain, projects through the thalamus, and ultimately reaches the cerebral cortex. Damage to any component of this system—whether through direct injury, metabolic disruption, or toxic insult—can result in unconsciousness.

Why Understanding Unconscious Patient Management Matters

Emergency Care for Unconscious Patients represents a time-sensitive medical emergency where early physiological stabilization and accurate diagnosis directly impact patient outcomes and long-term prognosis. The mortality rate for non-traumatic unconscious patients varies dramatically from 25% to 87%, depending on the underlying cause and speed of appropriate intervention.

For medical students and doctors, mastering the systematic approach to unconscious patients provides several critical advantages:

Clinical Competence: Emergency departments, intensive care units, and general medical wards frequently encounter unconscious patients, making this skill essential for daily practice.

Patient Safety: Unconscious patients lose protective reflexes and remain vulnerable to aspiration, airway obstruction, anoxic brain injury, and skin ulcerations without proper management.

Prognostic Assessment: Early neurological evaluation using tools like the Glasgow Coma Scale helps predict outcomes and guides discussions with families regarding goals of care.

Differential Diagnosis Skills: The systematic approach to unconscious patients strengthens clinical reasoning by requiring integration of history, examination findings, and investigation results.

Exam Success: Understanding unconscious patient management remains a high-yield topic for MBBS examinations, OSCE scenarios, and medical licensing exams worldwide.

Studies demonstrate that structured protocols like “coma alarms” and systematic checklists significantly improve assessment quality and treatment outcomes for unconscious patients. The interprofessional team approach—involving emergency physicians, neurologists, critical care specialists, and nursing staff—optimizes both immediate care and long-term recovery.

Common Causes of Unconsciousness

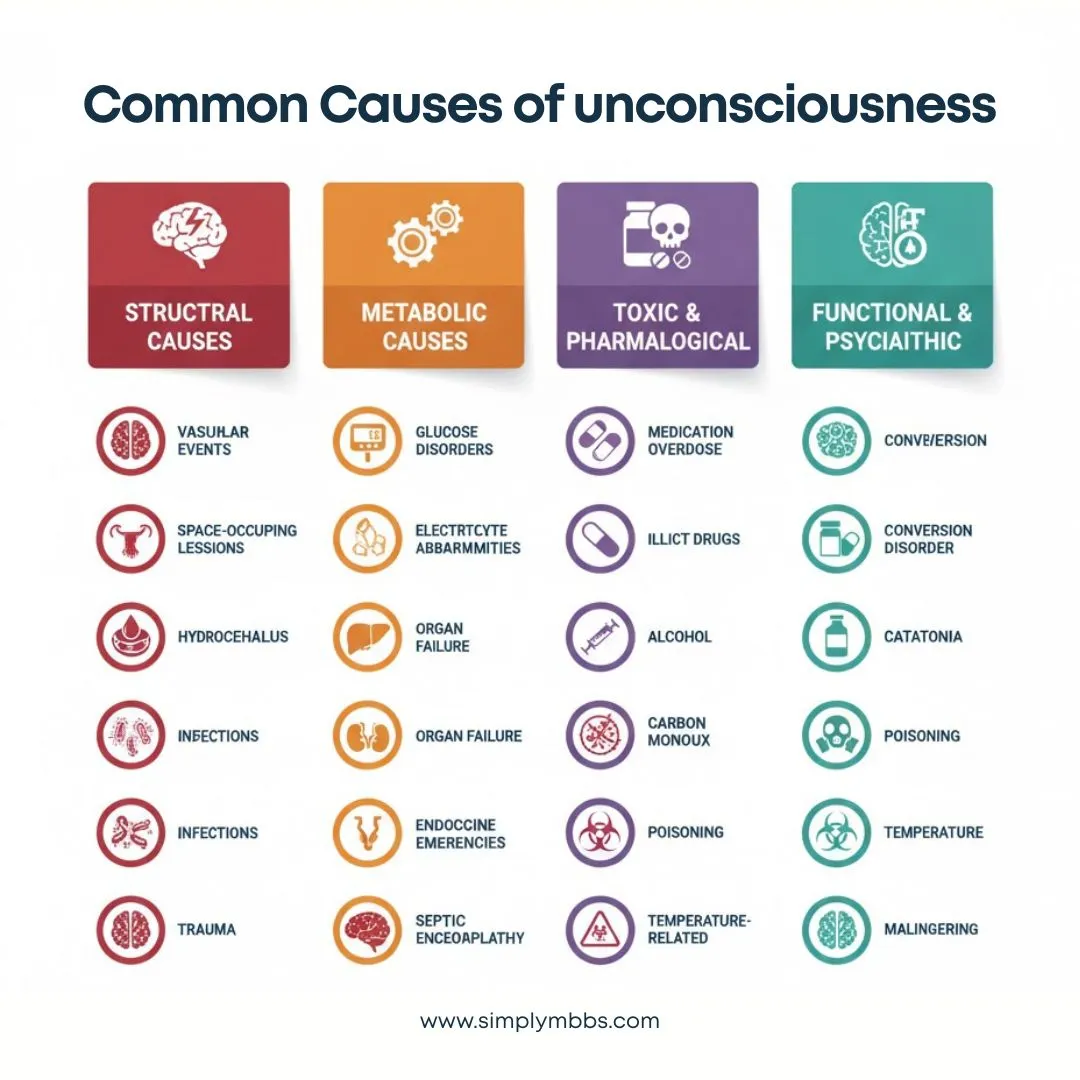

Understanding the Causes of Unconsciousness requires a systematic framework that helps clinicians rapidly generate differential diagnoses at the bedside. Medical causes can be broadly categorized into four main groups: structural, metabolic, diffuse physiological dysfunction, and psychiatric/functional causes.

Structural Causes

Structural causes involve direct damage to brain tissue or compression of neural structures, accounting for 28-64% of non-traumatic unconscious patients.

Vascular Events: Ischemic stroke, particularly involving the brainstem or bilateral hemispheres, represents the most common structural cause of unconsciousness. Intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and subdural hematomas can cause unconsciousness through direct tissue damage or secondary effects like elevated intracranial pressure.

Space-Occupying Lesions: Brain tumors, cerebral lymphoma, brain metastases, and cerebral abscesses produce unconsciousness through mass effect, midline shift, and herniation syndromes.

Hydrocephalus and Edema: Acute hydrocephalus obstructs cerebrospinal fluid flow, causing rapid deterioration in consciousness. Cerebral edema from various causes increases intracranial pressure and compromises cerebral perfusion.

Infections: Central nervous system infections including bacterial meningitis, viral encephalitis, and cerebral abscesses can cause unconsciousness through direct neural damage, inflammation, and elevated intracranial pressure.

Trauma: Even in the absence of obvious external injury, particularly in elderly patients or those on anticoagulation, traumatic brain injury and intracranial bleeding must be considered.

Metabolic Causes

Metabolic causes disrupt normal neuronal function by creating abnormal physiological environments, accounting for a substantial proportion of unconscious patients.

Glucose Disorders: Hypoglycemia represents the most immediately reversible cause of unconsciousness and must be excluded with bedside glucose testing in every unconscious patient. Severe hyperglycemia, particularly diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state, can also cause altered consciousness.

Electrolyte Abnormalities: Hyponatremia, hypernatremia, hypercalcemia, and severe electrolyte disturbances alter neuronal membrane potentials and synaptic transmission.

Organ Failure: Hepatic encephalopathy from liver failure, uremic encephalopathy from kidney failure, and hypercapnia from respiratory failure all produce metabolic encephalopathy.

Endocrine Emergencies: Addisonian crisis, myxedema coma, pituitary apoplexy, and thyroid storm can present with altered consciousness.

Septic Encephalopathy: Systemic infections cause diffuse brain dysfunction through inflammatory mediators, even without direct CNS infection.

Toxic and Pharmacological Causes

Diffuse physiological brain dysfunction from drugs, toxins, and poisoning represents 1-39% of unconscious patients, typically with better prognosis when recognized early.

Medication Overdose: Opioid toxicity, benzodiazepine overdose, tricyclic antidepressants, and sedative medications commonly cause unconsciousness.

Illicit Drug Use: Recreational drug overdoses, particularly synthetic opioids and designer drugs, increasingly contribute to unconscious presentations.

Alcohol: Excessive alcohol intake causes unconsciousness through direct CNS depression, though clinicians must always search for concurrent causes.

Carbon Monoxide Poisoning: This odorless gas binds hemoglobin with higher affinity than oxygen, causing cellular hypoxia and unconsciousness.

Poisoning: Heavy metal poisoning, organophosphate exposure, and various toxins can produce altered consciousness.

Temperature-Related: Severe hypothermia and hyperthermia both impair neuronal function and cause unconsciousness.

Functional and Psychiatric Causes

Psychogenic causes should only be considered after excluding organic etiologies through comprehensive medical and neurological evaluation.

Conversion Disorder: Functional neurological symptom disorder can present with apparent unconsciousness but maintains normal protective reflexes and EEG patterns.

Catatonia: Severe psychiatric conditions may present with unresponsiveness and altered motor activity.

Malingering: Deliberate feigning of unconsciousness typically shows inconsistent findings, with patients actively resisting eye opening and displaying normal reflexes.

Mnemonic for Causes: The “AEIOU TIPS” mnemonic helps recall common causes:

- Alcohol, Epilepsy, Insulin (hypoglycemia), Opiates, Uremia

- Trauma, Infection, Psychiatric, Stroke

Read More : Heart Failure: Classification, Diagnosis & Notes

The ABCDE Approach to Unconscious Patients

The Approach to Unconscious Patient using the ABCDE methodology provides a systematic, prioritized framework that addresses life-threatening problems before proceeding to detailed assessment. This structured approach has been validated across emergency medicine, acute medicine, and critical care settings worldwide.

The fundamental principle of the ABCDE approach involves simultaneous assessment and treatment, with continuous reassessment to monitor response to interventions. Teams should call for help early and delegate tasks among team members to accelerate both evaluation and management.

A – Airway Assessment and Management

Airway compromise represents the most immediate threat to life in unconscious patients. The absence of protective reflexes places patients at high risk for aspiration, obstruction, and hypoxic injury.

Assessment Steps:

- Look for airway patency by observing chest rise and listening for air movement

- Check for obstruction from blood, vomit, foreign bodies, or tongue displacement

- Listen for abnormal sounds: gurgling (fluid), stridor (upper airway obstruction), or silence (complete obstruction)

- Assess gag and cough reflexes, which indicate brainstem function

Management Interventions:

- Position the patient appropriately with head tilt-chin lift or jaw thrust (if no cervical spine injury suspected)

- Suction visible secretions using rigid yankauer suction catheter

- Insert oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airway adjuncts as tolerated

- Consider definitive airway protection through endotracheal intubation for patients with GCS ≤8, absent protective reflexes, or inadequate oxygenation despite supplemental oxygen

- Immobilize cervical spine if any possibility of trauma until clinical or radiological clearance

Critical Decision Point: Patients with GCS scores of 8 or less typically require intubation to protect the airway and prevent aspiration pneumonia.

B – Breathing Evaluation

Breathing assessment evaluates both adequacy of ventilation and potential causes of unconsciousness related to respiratory dysfunction.

Assessment Parameters:

- Measure respiratory rate (normal 12-20 breaths/minute in adults)

- Observe depth, pattern, and work of breathing

- Check oxygen saturation using pulse oximetry (target SpO2 >94%)

- Auscultate chest for air entry, adventitious sounds, and symmetry

- Palpate chest wall for trauma, crepitus, or surgical emphysema

Breathing Pattern Recognition:

Abnormal respiratory patterns provide diagnostic clues about the underlying cause and level of brainstem dysfunction:

Kussmaul Respiration: Deep, labored breathing indicates severe metabolic acidosis, commonly seen in diabetic ketoacidosis.

Cheyne-Stokes Breathing: Cyclical pattern of gradual increase then decrease in respiratory depth, followed by apnea, suggests bilateral hemispheric dysfunction or heart failure.

Central Neurogenic Hyperventilation: Rapid, deep breathing (>25 breaths/minute) indicates pontine or midbrain lesions.

Ataxic Breathing (Biot’s Respiration): Irregular, unpredictable breathing with variable tidal volumes suggests lower pontine or medullary lesions and carries poor prognosis.

Shallow, Depressed Breathing: Very slow respiratory rate suggests opioid overdose or sedative toxicity.

Management Interventions:

- Administer high-flow oxygen to achieve adequate saturation

- Obtain arterial blood gas analysis including carbon monoxide levels

- Provide assisted ventilation with bag-valve-mask if respiratory effort inadequate

- Prepare for mechanical ventilation if respiratory failure present

C – Circulation Monitoring

Circulation assessment ensures adequate cerebral perfusion pressure while identifying cardiovascular causes of unconsciousness.

Assessment Components:

- Measure heart rate, blood pressure, and calculate mean arterial pressure (MAP)

- Assess peripheral perfusion through capillary refill time, skin temperature, and color

- Palpate central and peripheral pulses for rate, rhythm, and volume

- Look for signs of shock: hypotension, tachycardia, cold extremities

- Perform 12-lead electrocardiogram to exclude cardiac causes

Hemodynamic Targets:

- Maintain mean arterial pressure >70 mmHg to ensure adequate cerebral perfusion

- Treat severe hypertension (MAP >130 mmHg) cautiously to avoid sudden drops in cerebral perfusion

Management Interventions:

- Establish intravenous access with large-bore cannulas

- Administer intravenous fluid resuscitation for hypotension

- Consider vasopressor support if fluids insufficient to maintain blood pressure

- Treat severe hypertension with careful blood pressure control using IV labetalol 5-20 mg

- Connect cardiac monitoring for continuous rhythm assessment

D – Disability (Neurological Assessment)

Disability assessment evaluates neurological function to determine the depth of unconsciousness and localize potential lesions.

Consciousness Level Evaluation:

Measure consciousness level using the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), which provides objective, reproducible assessment. Document GCS score immediately upon arrival and repeat regularly to track trends.

Glasgow Coma Scale Components (detailed in next section):

- Eye opening response (1-4 points)

- Verbal response (1-5 points)

- Motor response (1-6 points)

- Total score ranges from 3 (deep coma) to 15 (fully conscious)

Bedside Blood Glucose Testing:

Perform capillary blood glucose measurement immediately in every unconscious patient to exclude hypoglycemia. This represents the single most important bedside test, as hypoglycemia is rapidly reversible but can cause permanent brain damage if untreated.

Pupillary Examination:

Pupil size and reactivity provide crucial information about brainstem function and help localize lesions:

- Small pupils (<2 mm): Suggest opioid toxicity or pontine lesion

- Midsize unreactive pupils (4-6 mm): Indicate midbrain lesion

- Large dilated pupils (>8 mm): Seen with anticholinergic toxicity or severe hypoxia

- Unilateral dilated pupil: Suggests third nerve compression from uncal herniation

Additional Neurological Signs:

- Assess motor response to painful stimuli bilaterally

- Check for abnormal posturing (decorticate or decerebrate)

- Examine for neck stiffness suggesting meningitis (if no trauma)

- Perform fundoscopy to identify papilledema or retinal hemorrhages

Management Interventions:

- If hypoglycemia detected, administer 25g dextrose IV immediately (or 50ml of 50% dextrose)

- Give thiamine 100mg IV before or with glucose in malnourished patients or alcoholics to prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy

- Consider naloxone for suspected opioid overdose

- Maintain 30-degree head elevation if raised intracranial pressure suspected

E – Exposure and Environmental Control

Exposure involves complete examination of the patient while maintaining dignity and preventing hypothermia.

Assessment Actions:

- Fully expose the patient to identify signs of trauma, rashes, or injection marks

- Measure core body temperature (rectal or tympanic)

- Search for medical alert bracelets, medication bottles, or other clues

- Look for needle tracks suggesting drug use

- Check for meningococcal rash or petechiae

- Inspect for bruising, wounds, or fractures indicating trauma

Temperature Management:

- Treat hyperthermia (>38.5°C) with cooling measures and antipyretics to prevent secondary brain injury

- Rewarm hypothermic patients unless temperature >33°C

- Consider targeted temperature management for post-cardiac arrest patients

Environmental Control:

- Maintain patient warmth with blankets after examination

- Ensure appropriate monitoring equipment attached

- Position patient to prevent pressure injuries

Detailed Neurological Assessment Tools for Unconscious Patient

Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) Scoring

The Glasgow Coma Scale provides standardized, objective measurement of consciousness level and serves as the gold standard worldwide for assessing unconscious patients. Developed by Teasdale and Jennett in 1974, the GCS has been validated across multiple populations and clinical settings.

GCS Scoring System:

| Category | Response | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Eye Opening (E) | Spontaneous | 4 |

| To speech | 3 | |

| To pain | 2 | |

| None | 1 | |

| Verbal Response (V) | Oriented | 5 |

| Confused | 4 | |

| Inappropriate words | 3 | |

| Incomprehensible sounds | 2 | |

| None | 1 | |

| Motor Response (M) | Obeys commands | 6 |

| Localizes pain | 5 | |

| Withdraws from pain | 4 | |

| Abnormal flexion | 3 | |

| Abnormal extension | 2 | |

| None | 1 |

Score Interpretation:

- GCS 13-15: Mild impairment

- GCS 9-12: Moderate impairment

- GCS 3-8: Severe impairment (coma)

Clinical Application Tips:

Record GCS as both total score and individual components (e.g., GCS 9 = E2 V3 M4). This provides more detailed information than total score alone and helps identify specific deficits.

For intubated patients, verbal score cannot be assessed—document as “VT” (verbal intubated) and report as GCS E_V_T_M_.

Assess the best response observed, not average performance. Test painful stimuli using supraorbital pressure, trapezius squeeze, or nailbed pressure—avoid sternal rub in suspected spinal injury.

Prognostic Value:

Lower GCS scores correlate with higher mortality and worse functional outcomes. GCS performed before sedation or intubation provides the most accurate prognostic information. Serial GCS measurements track clinical trajectory and response to interventions.

FOUR Score System

The Full Outline of UnResponsiveness (FOUR) Score provides an alternative coma scale that includes brainstem reflexes and respiratory patterns, offering advantages over GCS in certain situations.

FOUR Score Components:

Eye Response (0-4):

- 4: Eyelids open, tracking or blinking to command

- 3: Eyelids open, not tracking

- 2: Eyelids closed, open to loud voice

- 1: Eyelids closed, open to pain

- 0: Eyelids remain closed with pain

Motor Response (0-4):

- 4: Thumbs-up, fist, or peace sign

- 3: Localizing to pain

- 2: Flexion response to pain

- 1: Extension response to pain

- 0: No response or myoclonic status

Brainstem Reflexes (0-4):

- 4: Pupil and corneal reflexes present

- 3: One pupil wide and fixed

- 2: Pupil or corneal reflex absent

- 1: Pupil and corneal reflexes absent

- 0: Absent pupil, corneal, and cough reflexes

Respiration (0-4):

- 4: Not intubated, regular breathing

- 3: Not intubated, Cheyne-Stokes breathing

- 2: Not intubated, irregular breathing

- 1: Breathes above ventilator rate

- 0: Breathes at or below ventilator rate

Advantages Over GCS:

- Can be performed in intubated patients without verbal component limitation

- Assesses brainstem reflexes directly

- Evaluates respiratory patterns

- Maximum score remains 16, similar to GCS maximum of 15

Pupillary Examination

Pupil assessment provides critical information about brainstem function, herniation syndromes, and toxic exposures.

Systematic Pupillary Exam:

- Measure pupil size in millimeters using pupilometer or size guide

- Check symmetry—anisocoria suggests structural lesion

- Test light reflex response speed and completeness

- Assess for consensual light reflex

Clinical Significance of Pupil Findings:

Small Reactive Pupils (1-2mm): Suggest opioid overdose, cholinergic toxicity (organophosphates), or pontine hemorrhage.

Midsize Fixed Pupils (4-6mm): Indicate midbrain damage, often with poor prognosis.

Large Fixed Pupils (>7mm): Seen with anticholinergic toxicity (e.g., atropine), severe anoxia, or hypothermia.

Unilateral Dilated Fixed Pupil: Classic sign of uncal herniation with third nerve compression, medical emergency requiring immediate neurosurgical consultation.

Pinpoint Pupils: Highly specific for opioid toxicity when combined with decreased respiratory rate and altered consciousness.

Read More : Pneumonia: Clinical Approach, Diagnosis & Management

Differential Diagnosis and Clinical Clues of Unconscious Patient

Unconscious Patient Diagnosis relies heavily on pattern recognition and integration of multiple clinical findings to rapidly narrow differential diagnosis.

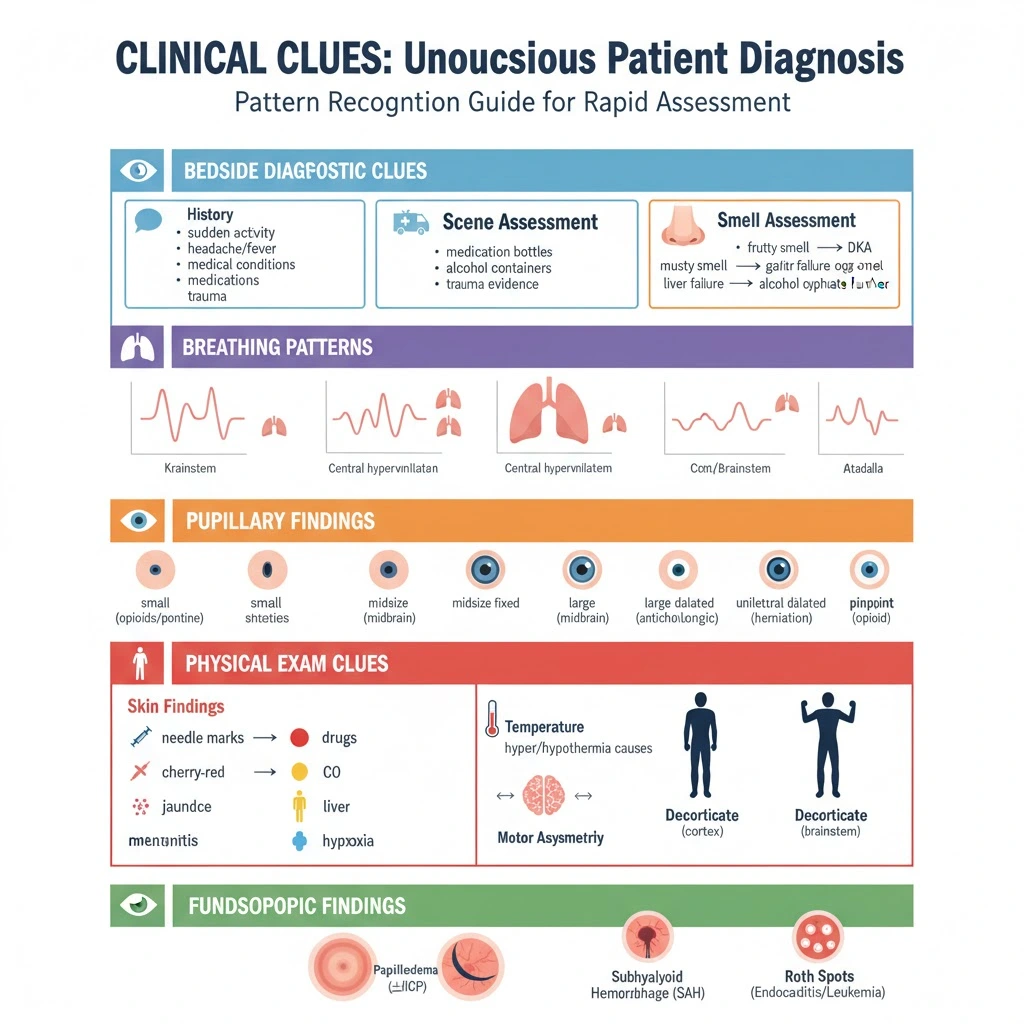

Bedside Diagnostic Clues

Historical Clues from Witnesses:

Collateral history from family, bystanders, or paramedics provides invaluable diagnostic information. Key questions include:

- Timeline of symptom onset (sudden vs. gradual)

- Witnessed seizure activity or jerking movements

- Recent complaints of headache, fever, or focal symptoms

- Known medical conditions (diabetes, epilepsy, cardiac disease)

- Medication list and potential overdose

- Recent trauma or falls

Scene Assessment:

Paramedics often gather crucial clues at the scene: empty medication bottles, alcohol containers, suicide notes, evidence of trauma, or environmental hazards like carbon monoxide sources.

Smell Assessment:

Distinctive breath odors provide diagnostic clues:

- Fruity/ketotic smell: Diabetic ketoacidosis

- Musty/fetor hepaticus: Hepatic encephalopathy

- Garlic smell: Organophosphate poisoning

- Alcohol smell: Does NOT exclude other causes—always investigate further

Breathing Patterns Recognition

Abnormal breathing patterns (covered in ABCDE section) help localize anatomical lesions and suggest specific etiologies.

Pupillary Findings

Pupil examination patterns (covered in neurological assessment section) differentiate structural from metabolic causes and identify specific toxidromes.

Additional Physical Examination Clues:

Skin Findings:

- Needle marks: Drug injection

- Cherry-red skin: Carbon monoxide poisoning

- Jaundice: Hepatic encephalopathy

- Purpuric rash: Meningococcemia

- Cyanosis: Severe hypoxia

Temperature Patterns:

- Hyperthermia: Infection, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, serotonin syndrome, heat stroke

- Hypothermia: Environmental exposure, hypothyroidism, sepsis

Motor Asymmetry:

Unilateral weakness or asymmetric motor responses strongly suggest structural brain lesion on the contralateral side.

Decorticate vs. Decerebrate Posturing:

Decorticate posturing (upper extremity flexion, lower extremity extension) indicates lesions at or above the midbrain.

Decerebrate posturing (all extremity extension) suggests brainstem damage below the red nucleus and carries worse prognosis.

Fundoscopic Findings:

- Papilledema: Raised intracranial pressure

- Subhyaloid hemorrhage: Subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Roth spots: Bacterial endocarditis

Essential Investigations for Unconscious Patients

Emergency treatment for unconscious patients in hospitals requires simultaneous investigation and management. The mnemonic “Don’t Ever Forget Glucose” emphasizes that bedside glucose testing represents the single most critical initial investigation.

Immediate Bedside Tests

Capillary Blood Glucose:

Perform finger-stick glucose testing within the first minute of assessment in every unconscious patient. Hypoglycemia represents the most rapidly reversible cause of unconsciousness and cannot be diagnosed clinically with sufficient reliability. Even if capillary glucose appears normal, send laboratory venous glucose for confirmation.

Point-of-Care Testing:

- Blood gas analysis (arterial or venous)

- Lactate level

- Electrolytes (iSTAT or similar device)

- Ketones (blood or urine)

- ECG interpretation for cardiac causes

Laboratory Investigations

Initial Blood Tests:

| Test Category | Specific Tests | Diagnostic Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Complete Blood Count | Hemoglobin, WBC, Platelets | Infection, anemia, hematological disorders |

| Biochemistry | Sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate | Electrolyte disorders, acid-base disturbances |

| Renal Function | Urea, creatinine, eGFR | Uremic encephalopathy, kidney failure |

| Liver Function | ALT, AST, bilirubin, albumin | Hepatic encephalopathy, liver failure |

| Glucose | Venous glucose | Hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia confirmation |

| Calcium & Bone Profile | Calcium, phosphate, albumin | Hypercalcemia, metabolic bone disorders |

| Coagulation | PT/INR, aPTT | Bleeding risk, warfarin toxicity |

| Thyroid Function | TSH, Free T4 | Myxedema coma, thyroid storm |

Arterial Blood Gas Analysis:

ABG provides crucial information beyond oxygenation:

- pH and acid-base status (metabolic acidosis suggests poisoning, DKA, sepsis)

- PaCO2 (hypo/hyperventilation)

- PaO2 and A-a gradient (respiratory failure)

- Carbon monoxide level (carboxyhemoglobin)

- Lactate (tissue hypoxia, sepsis)

Toxicology Screening:

Comprehensive toxicology panel should include:

- Paracetamol (acetaminophen) level

- Salicylate level

- Blood alcohol level

- Urine drug screen for common substances

- Specific levels based on clinical suspicion (digoxin, lithium, anticonvulsants)

Additional Laboratory Tests:

Blood cultures before antibiotic administration if sepsis or meningitis suspected. Ammonia level if hepatic encephalopathy considered. Cortisol and ACTH for suspected adrenal crisis. Serum osmolality for toxic alcohol ingestion.

Neuroimaging Protocols of Unconscious Patient

CT Brain Scan:

Non-contrast CT brain represents the first-line neuroimaging for unconscious patients and should be performed urgently when the cause is not immediately obvious. CT can be obtained rapidly and identifies:

- Intracranial hemorrhage (intracerebral, subarachnoid, subdural, epidural)

- Ischemic stroke (after several hours)

- Space-occupying lesions (tumors, abscesses)

- Hydrocephalus

- Midline shift and herniation

- Skull fractures

- Cerebral edema

Indications for Urgent CT Brain:

- Focal neurological signs

- Recent head trauma

- Anticoagulation therapy

- Progressive deterioration in GCS

- Unknown cause after initial assessment

- Suspected increased intracranial pressure

MRI Brain:

When CT brain appears normal but diagnosis remains unclear, MRI provides superior sensitivity for:

- Early ischemic stroke (diffusion-weighted imaging)

- Posterior fossa lesions

- Brainstem pathology

- Encephalitis (especially herpes simplex)

- Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES)

- Venous sinus thrombosis

- Small metastases

CT or MR Angiography:

Vascular imaging evaluates cerebral blood vessels for:

- Aneurysms in subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Vascular occlusions in stroke

- Arterial dissections

- Venous sinus thrombosis

When to Perform Lumbar Puncture

Lumbar puncture provides essential diagnostic information when central nervous system infection suspected or diagnosis remains unclear after neuroimaging.

Indications:

- Suspected meningitis or encephalitis

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage with negative CT

- Multiple sclerosis or demyelinating disease

- Carcinomatous meningitis

- Normal pressure hydrocephalus

- Unexplained altered consciousness after normal CT

Contraindications:

- Signs of raised intracranial pressure with mass effect on CT

- Coagulopathy (relative)

- Local infection at puncture site

- Hemodynamic instability (relative)

Critical Management Point: If bacterial meningitis suspected clinically, never delay empiric antibiotics while waiting for lumbar puncture or imaging. Administer ceftriaxone 2g IV and vancomycin 15-20mg/kg IV immediately, along with acyclovir 10mg/kg IV if viral encephalitis possible.

Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis:

Send CSF for:

- Opening pressure measurement

- Cell count and differential

- Gram stain and bacterial culture

- Glucose and protein

- Viral PCR panel (HSV, VZV, enteroviruses)

- Additional tests based on clinical scenario (cryptococcal antigen, TB culture, cytology)

Electroencephalography (EEG):

Request EEG when:

- Non-convulsive status epilepticus suspected (subtle seizure activity without obvious motor signs)

- Diagnosis remains unclear despite full workup

- Suspected encephalitis

- Distinguishing structural from metabolic causes

- Assessing for epileptiform activity

Non-convulsive status epilepticus occurs more commonly in elderly patients and presents with staring, nystagmoid eye movements, lip smacking, or subtle myoclonic jerks. EEG diagnosis enables specific anti-epileptic treatment.

Emergency Management Protocols for Unconscious Patient

Medical Management of Unconscious Patient follows simultaneous assessment and treatment principles, with continuous reassessment guiding therapeutic adjustments.

Initial Resuscitation Steps

Immediate Life-Saving Interventions (First 5 Minutes):

-

Ensure Scene Safety: Protect healthcare workers and patient from ongoing hazards

-

ABCDE Resuscitation: Follow systematic ABCDE approach as detailed above

-

Administer Empiric Therapy:

-

Oxygen: High-flow oxygen if SpO2 <90%

-

Glucose: If bedside glucose <3.0 mmol/L or unable to test immediately, give 25g dextrose (50ml of 50% dextrose) IV push

-

Thiamine: 100mg IV if malnourished, alcoholic, or before glucose administration to prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy

-

Naloxone: 0.4-2mg IV if suspected opioid overdose (small pupils, depressed respirations)

-

-

Establish Monitoring:

-

Continuous cardiac monitoring

-

Pulse oximetry

-

Non-invasive blood pressure (or arterial line if critically unwell)

-

Temperature monitoring

-

-

Call for Help: Activate medical emergency team, intensive care team, or relevant specialists early

Specific Treatment Interventions for Unconscious Patient

Hypoglycemia Management:

Intravenous glucose provides immediate treatment for hypoglycemia. Glucagon administration takes up to 15 minutes to work and fails in patients with depleted glycogen stores (liver disease, malnutrition, chronic alcohol use). After initial glucose bolus, start glucose infusion (10% dextrose) to prevent recurrence and recheck glucose every 30 minutes initially.

Opioid Toxicity:

Naloxone 0.4-2mg IV reverses opioid-induced respiratory depression and altered consciousness. Use caution with naloxone in opioid-dependent patients as it may precipitate acute withdrawal. Repeat doses or continuous infusion may be required for long-acting opioids.

Benzodiazepine Overdose:

Flumazenil 0.2mg IV can reverse benzodiazepine effects but carries significant risks. Contraindications include known seizure disorder and potential tricyclic antidepressant co-ingestion, as flumazenil may precipitate seizures in these situations. Generally, supportive care with airway management preferred over routine flumazenil administration.

Seizure Control:

If seizures witnessed or suspected, administer anti-epileptic medications:

- First-line: Lorazepam 4mg IV or diazepam 10mg IV

- Second-line: Levetiracetam 2000-3000mg IV or phenytoin 18-20mg/kg IV (loading dose)

- Status epilepticus protocol if seizures persist beyond 5 minutes

For suspected non-convulsive status epilepticus, empiric treatment with IV phenytoin or levetiracetam may be indicated pending EEG confirmation.

Raised Intracranial Pressure Management:

If herniation syndrome evident (unilateral dilated pupil, decerebrate posturing, rapid GCS decline) or CT shows mass effect with midline shift:

- Elevate head of bed to 30 degrees

- Maintain adequate mean arterial pressure (>70 mmHg)

- Administer osmotic therapy: Mannitol 1g/kg IV bolus or hypertonic saline 3% 250ml IV

- Brief hyperventilation (target PaCO2 30-35 mmHg) as temporizing measure

- Urgent neurosurgical consultation for potential surgical decompression

Avoid excessive hyperventilation, as PaCO2 <30 mmHg causes cerebral vasoconstriction and may worsen ischemia.

Infection Treatment:

For suspected bacterial meningitis or encephalitis, immediately administer empiric antimicrobials without waiting for lumbar puncture results:

- Ceftriaxone 2g IV (or cefotaxime 2g IV)

- Vancomycin 15-20mg/kg IV

- Acyclovir 10mg/kg IV (for possible herpes encephalitis)

- Add ampicillin if Listeria risk (age >50, immunocompromised)

Acid-Base and Electrolyte Correction:

Severe electrolyte abnormalities require gradual correction to avoid complications:

- Hyponatremia: Correct slowly (<10-12 mmol/L per 24 hours) to prevent osmotic demyelination syndrome

- Hypernatremia: Correct gradually to avoid cerebral edema

- Hypercalcemia: IV fluids, bisphosphonates, calcitonin

- Metabolic acidosis: Treat underlying cause, consider bicarbonate only if pH <7.1

Temperature Management:

Hyperthermia (>38.5°C): Administer antipyretics (paracetamol 1g IV/PO), use cooling blankets or tepid sponging, identify and treat infectious causes. Hyperthermia worsens neurological injury and must be controlled aggressively.

Hypothermia (<35°C): Passive rewarming with warm blankets for mild hypothermia; active rewarming with warmed IV fluids, forced-air warming devices for severe hypothermia (<32°C).

When to Intubate

Indications for Endotracheal Intubation:

- GCS ≤8 (inability to protect airway)

- Absent gag or cough reflex

- SpO2 <90% despite high-flow oxygen

- Inadequate respiratory effort or apnea

- Anticipation of clinical deterioration (e.g., severe poisoning with delayed effects)

- Need for hyperventilation in herniation syndrome

- Requirement for prolonged airway protection during transport or procedures

Pre-Intubation Considerations:

Ensure senior anesthetist or emergency physician performs intubation. Rapid sequence induction with cricoid pressure minimizes aspiration risk. Have difficult airway equipment immediately available. Document pre-intubation GCS score for prognostic purposes.

Critical Care Referral Criteria

Indications for ICU Admission:

- Persistent coma despite initial interventions

- Requires intubation and mechanical ventilation

- Hemodynamic instability requiring vasopressor support

- Need for continuous monitoring and frequent neurological reassessment

- Multi-organ dysfunction

- Suspected raised intracranial pressure requiring ICP monitoring

- Poisoning requiring specific antidote infusions or extracorporeal elimination

Specialist Consultation:

Contact neurology or neurosurgery for structural brain lesions requiring specialized management or potential surgical intervention. Involve toxicology services for complex poisoning cases. Engage palliative care team early when prognosis appears poor and ceiling of care discussions needed with family.

Read More : ECG Interpretation: Stepwise Guide for Undergraduates

Common Mistakes to Avoid for Unconscious Patient

First aid for unconscious patients and initial emergency management commonly involve several critical errors that compromise patient outcomes.

Failure to Check Glucose Immediately:

The most common and most dangerous error involves not performing bedside glucose testing within the first minute of assessment. Hypoglycemia causes rapid, irreversible brain damage yet represents the most easily treatable cause of unconsciousness. Never rely on clinical impression alone—always confirm glucose level objectively.

Delaying Airway Protection:

Waiting too long to intubate patients with GCS ≤8 or absent protective reflexes risks aspiration pneumonia and hypoxic brain injury. When in doubt about airway security, intubate early rather than late.

Assuming Alcohol Explains Everything:

The smell of alcohol on breath does NOT exclude serious concurrent pathology. Many drunk patients have fallen and sustained intracranial hemorrhage, or have ingested other substances alongside alcohol. Always perform complete evaluation including CT brain in intoxicated unconscious patients, especially elderly or anticoagulated individuals.

Giving “Coma Cocktails”:

Avoid empirically administering combinations of glucose, naloxone, and flumazenil without specific indications. Flumazenil carries significant risks including seizure precipitation and should only be used in confirmed isolated benzodiazepine overdose without seizure history.

Not Involving Senior Support Early:

Junior doctors attempting to manage complex unconscious patients alone delays definitive interventions and specialist input. Call for senior medical staff, anesthesia, and intensive care support immediately upon recognizing unconscious patient.

Inadequate Immobilization in Potential Trauma:

Even without obvious external injury, unconscious patients (particularly elderly, anticoagulated, or with unclear history) may have cervical spine injury. Maintain spinal precautions until imaging or clinical assessment excludes spinal injury.

Delaying Antibiotics in Suspected Meningitis:

Never postpone empiric antibiotics while arranging lumbar puncture or CT brain when meningitis suspected clinically. Every hour delay in antibiotic administration increases mortality and morbidity.

Over-Aggressive Blood Pressure Reduction:

Rapid lowering of elevated blood pressure in unconscious patients may worsen cerebral perfusion and expand ischemic areas. Unless blood pressure exceeds MAP 130 mmHg or specific conditions require control (e.g., thrombolysis for stroke), permit permissive hypertension to maintain cerebral perfusion.

Insufficient Communication with Family:

Failing to involve family members early in the care process misses valuable collateral history and leaves relatives anxious without updates. Senior physicians must communicate with family regarding diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment plans, especially when outcomes appear unfavorable.

Not Rechecking and Reassessing:

Single assessment of unconscious patients provides insufficient information. Serial GCS measurements, repeated vital signs, and continuous reassessment identify clinical trends—improvement or deterioration—that guide management adjustments.

Missing Non-Convulsive Status Epilepticus:

Unconscious patients without obvious seizure activity may have ongoing electrical seizures causing their coma. Consider EEG in any unconscious patient without clear alternative diagnosis, especially if subtle myoclonic jerks or eye deviation present.

Comparison: GCS vs FOUR Score

Both the Glasgow Coma Scale and FOUR Score provide validated tools for assessing consciousness level in unconscious patients, but each offers distinct advantages depending on clinical circumstances.

| Feature | Glasgow Coma Scale | FOUR Score |

|---|---|---|

| Components | Eye opening, Verbal response, Motor response | Eye response, Motor response, Brainstem reflexes, Respiration |

| Maximum Score | 15 | 16 |

| Minimum Score | 3 | 0 |

| Intubated Patients | Cannot assess verbal component accurately | Full assessment possible without verbal component |

| Brainstem Testing | Not directly assessed | Includes pupil, corneal, cough reflexes |

| Respiratory Assessment | Not included | Evaluates breathing patterns |

| Training Required | Minimal, widely known | More extensive, less familiar to some staff |

| Validation | Extensively validated over 50 years | Well-validated but shorter track record |

| Prognostic Value | Excellent for traumatic brain injury | Comparable sensitivity and specificity |

| Clinical Use | Universal standard worldwide | Increasingly adopted in critical care |

| Advantages | Simple, rapid, universally understood | More detailed neurological information |

| Limitations | Cannot differentiate locked-in syndrome, less detail in deeply comatose patients | More complex, takes longer to perform |

When to Use Each Tool:

GCS preferred for:

- Initial emergency department assessment where rapid triage needed

- Settings where all staff familiar with GCS scoring

- Communication between services using universal language

- Traumatic brain injury assessment (extensive validation data)

- Patients with intact verbal response capability

FOUR Score preferred for:

- Intubated patients in intensive care units

- Patients with tracheostomy or other inability to speak

- When detailed brainstem assessment needed

- Distinguishing different depths of coma (all GCS 3 patients not equivalent)

- Identifying locked-in syndrome (preserved vertical eye movements)

- Respiratory pattern assessment important for diagnosis

Clinical Recommendation: Learn both scoring systems, as GCS remains the universal standard for communication, while FOUR Score provides additional neurological detail in critical care settings. Document both scores when feasible in complex unconscious patients.

Prognosis and Outcomes of Unconscious Patient

Managing unconscious patients in pre-hospital settings and subsequent hospital care produces highly variable outcomes depending on multiple factors.

Mortality Rates:

Overall mortality for non-traumatic unconscious patients ranges from 25% to 87%, with significant variation based on underlying etiology.

Highest Mortality (60-95%): Hemorrhagic stroke, anoxic brain injury post-cardiac arrest

Intermediate Mortality (40-60%): Ischemic stroke, bacterial meningitis, traumatic brain injury

Lowest Mortality (<10%): Seizures, drug overdose/poisoning, metabolic causes when promptly treated

Patients with non-traumatic unconsciousness lasting more than 6 hours face 1-month mortality approaching 76%.

Prognostic Factors:

GCS Score at Presentation: Lower initial GCS correlates strongly with worse outcomes. Patients presenting with GCS 3-5 have significantly higher mortality than those with GCS 7-10. However, GCS performed after sedation or intubation loses prognostic accuracy—document pre-intervention GCS whenever possible.

Age: Advancing age independently predicts worse outcomes across all causes of unconsciousness.

Motor Response: Motor function assessment provides the most reliable prognostic information. Absence of motor response or extensor posturing carries grave prognosis, while purposeful movement or withdrawal predicts better outcomes.

Neuro-ophthalmological Signs: Pupillary responses, eye movements, and brainstem reflexes consistently predict long-term outcomes. Absent pupillary light reflexes, absent corneal reflexes, and absent oculocephalic reflexes indicate severe brainstem dysfunction with poor prognosis.

Duration of Coma: Prolonged unconsciousness beyond 72 hours (excluding sedation) indicates worse prognosis, though specific causes vary significantly.

Etiology-Specific Factors:

Traumatic Brain Injury: Initial GCS, age, pupil reactivity, CT findings (mass lesions, midline shift), and presence of secondary insults (hypotension, hypoxia) predict outcomes. Mortality ranges 40-50% for severe TBI.

Stroke: Location (brainstem worse than hemispheric), size of infarct/hemorrhage, and presence of hemorrhagic transformation influence prognosis. Hemorrhagic stroke carries worse prognosis than ischemic stroke.

Anoxic Brain Injury: Duration of cardiac arrest, time to return of spontaneous circulation, and initial neurological examination predict outcomes. Hypothermia protocols improve outcomes in post-arrest coma.

Metabolic Causes: Generally favorable prognosis when underlying cause corrected, though delayed treatment allows permanent neurological damage.

Poisoning/Overdose: Usually excellent prognosis with supportive care and specific antidotes when available. Exceptions include substances causing direct CNS damage (methanol, carbon monoxide).

Infection: Bacterial meningitis outcomes depend on causative organism, time to antibiotic administration, and patient age. Viral encephalitis prognosis varies by virus type—herpes simplex carries significant mortality and morbidity despite treatment.

Favorable Prognostic Indicators:

- Reversible cause identified early

- Normal CT brain

- Absence of focal neurology

- Preserved brainstem reflexes

- Rapid improvement with initial treatment

- Young age

- No secondary brain injury (hypoxia, hypotension, hypoglycemia)

Poor Prognostic Indicators:

- Absent pupillary and corneal reflexes beyond 24 hours

- Absent motor response (GCS M1-M2)

- Severe structural brain damage on imaging

- Prolonged unconsciousness without improvement

- Multiple organ failure

- Advanced age with multiple comorbidities

Withdrawal of Care Considerations:

Patients not responding to initial treatment and remaining comatose often require critical care admission unless withdrawal of treatment and palliation more appropriate. Early senior physician communication with family or appropriate advocates remains essential, especially when prognosis poor. Discussions should address ceiling of care, consideration of future treatment withdrawal, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation decisions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q : What is the first thing to do when you encounter an unconscious patient?

A : Ensure scene safety first, then immediately call for help and begin the ABCDE assessment. Perform bedside glucose testing within the first minute, as hypoglycemia represents the most rapidly treatable cause of unconsciousness. If the patient has no pulse or abnormal breathing, immediately begin CPR according to basic life support protocols.

Q : What are the most common reversible causes of unconsciousness?

A : The most common reversible causes follow the “4 Hs and 4 Ts” mnemonic used in emergency medicine. The 4 Hs include hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), hypoxia (low oxygen), hypovolemia (shock), and hypothermia (low body temperature). The 4 Ts include toxins, cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, and thrombosis (stroke or pulmonary embolism). Hypoglycemia represents the single most rapidly reversible cause and must be checked immediately with bedside glucose testing. Drug overdoses, particularly opioid toxicity, also represent highly treatable causes when managed with naloxone.

Q : Can unconscious patients hear or feel pain?

A : Research suggests some unconscious patients retain varying degrees of awareness depending on the depth and cause of unconsciousness. Patients in lighter states may hear sounds and process information even when unable to respond. Pain perception varies—patients with intact brainstem function typically withdraw from painful stimuli, indicating pain processing. Healthcare providers should always assume unconscious patients can hear and feel, speaking respectfully and providing appropriate pain management. Studies on coma survivors reveal many retained auditory awareness and recalled bedside conversations.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

Approach to Unconscious Patient represents a critical emergency medicine skill requiring systematic assessment, rapid intervention, and continuous monitoring. The ABCDE methodology provides a structured framework ensuring life-threatening problems receive immediate attention while diagnostic evaluation proceeds simultaneously.

Every unconscious patient demands immediate bedside glucose testing—hypoglycemia remains the most rapidly reversible cause and cannot be diagnosed clinically. Securing the airway early in patients with GCS ≤8 prevents aspiration and hypoxic injury, while maintaining adequate cerebral perfusion through blood pressure management optimizes outcomes.

Understanding common causes through systematic categorization into structural, metabolic, toxic, and functional etiologies enables focused differential diagnosis. Pattern recognition of pupillary findings, breathing patterns, and motor responses accelerates diagnostic accuracy and treatment precision.

Key Clinical Pearls:

Never assume alcohol explains everything—always perform complete evaluation including neuroimaging when indicated. Do not delay antibiotics while arranging investigations if meningitis suspected. Document GCS before sedation for accurate prognostic information. Call for senior help early—complex unconscious patients require interprofessional teams.

Reversible causes including hypoglycemia, opioid toxicity, hypoxia, and seizures demand immediate recognition and specific treatment. Serial neurological assessments track clinical trajectory better than single measurements.

For MBBS students and doctors, mastering unconscious patient management builds clinical confidence and improves examination performance. Visit Simply MBBS at simplymbbs.com for more evidence-based medical content and subscribe to our newsletter for weekly clinical pearls, exam tips, and simplified medical explanations delivered to your inbox.