Every year, millions of patients worldwide enter emergency departments in a life-threatening condition called shock, where their bodies struggle to deliver enough oxygen to vital organs. Understanding Management of Shock: Types, Clinical Assessment, and Latest Guidelines in Resuscitation represents one of the most critical competencies for medical professionals, as delays in recognition or treatment can rapidly lead to irreversible organ damage and death. Whether you are an MBBS student preparing for examinations, a practicing physician refining your emergency skills, or someone curious about critical care medicine, mastering shock management can literally mean the difference between life and death.

The affects approximately 1 in 3 patients admitted to intensive care units, with septic shock alone carrying a mortality rate between 40-50% despite modern medical advances. The 2025 European Resuscitation Council and American Heart Association have released updated guidelines that incorporate breakthrough research on hemodynamic monitoring, point-of-care ultrasound, and targeted resuscitation strategies. This comprehensive guide will walk you through everything from basic definitions to advanced management protocols, ensuring you have the knowledge to recognize, assess, and treat this effectively in any clinical setting.

What is Shock?

According to Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine and the latest StatPearls medical reference, It is defined as a life-threatening manifestation of circulatory failure that leads to cellular and tissue hypoxia, resulting in cellular death and dysfunction of vital organs. The condition is characterized by decreased oxygen delivery and/or increased oxygen consumption, or inadequate oxygen utilization at the cellular level, leading to tissue hypoxia and metabolic dysfunction.

Clinical Definition: Shock most commonly manifests as hypotension, defined as systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg or mean arterial pressure (MAP) less than 65 mmHg, accompanied by signs of inadequate tissue perfusion. However, it is crucial to understand that hypotension is a late finding, and It can exist even when blood pressure readings appear normal due to compensatory mechanisms.

Pathophysiology of Shock

The pathophysiology of shock involves a complex cascade of events that begins at the cellular level. When tissues receive insufficient oxygen, cells shift from aerobic to anaerobic metabolism, producing lactate as a byproduct and resulting in metabolic acidosis. This acidosis further impairs cellular function, creates a decrease in regional blood flow, and worsens tissue hypoxia in a vicious cycle.

Shock progresses through three distinct stages: compensated shock (where physiological mechanisms maintain blood pressure through tachycardia and vasoconstriction), decompensated shock (where these mechanisms fail and classic shock symptoms appear), and irreversible shock (leading to multiorgan failure and death). Recognizing shock in its early, compensated phase is critical because therapeutic interventions are most effective before irreversible cellular damage occurs.

Why Understanding Shock Management Matters

The importance of mastering management of shock cannot be overstated for several compelling reasons. First, It is a medical emergency where every minute counts – studies show that mortality increases by approximately 10% for each hour that shock remains untreated. Second, It can result from dozens of different underlying conditions, requiring clinicians to simultaneously stabilize the patient while investigating the root cause.

For MBBS students and junior doctors, emergency management of shock represents a core clinical competency tested in university examinations, OSCE assessments, and licensing exams worldwide. Understanding shock demonstrates your grasp of integrated physiology, pharmacology, and clinical medicine. For practicing physicians, staying current with evolving resuscitation guidelines directly impacts patient outcomes in your emergency department or ICU.

From a public health perspective, conditions causing shock – including sepsis, trauma, myocardial infarction, and hemorrhage – rank among the leading causes of death globally. Improving shock recognition and management in both hospital and prehospital settings has the potential to save hundreds of thousands of lives annually. Furthermore, survivors of shock often face long-term morbidity, extended hospitalization, and reduced quality of life, making early, effective intervention economically and humanely crucial.

Read More : Acute Myocardial Infarction (MI): ECG Changes, Early Treatment, and Post-MI Care

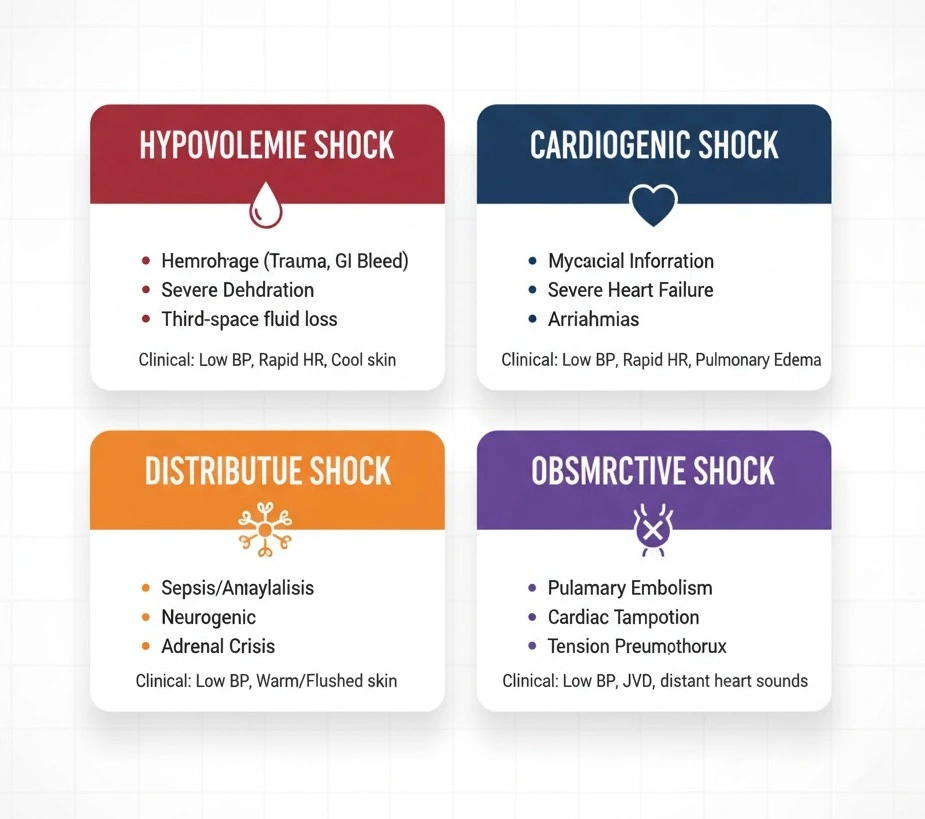

Types of Shock: Complete Classification

Medical literature categorizes shock into four major types based on underlying pathophysiology: distributive, hypovolemic, cardiogenic, and obstructive. Understanding the types of shock is essential because each requires different management approaches despite sharing common clinical features.

Hypovolemic Shock

Hypovolemic shock results from decreased intravascular volume, leading to inadequate venous return and reduced cardiac output. This represents the most straightforward type of shock conceptually – the heart has insufficient fluid to pump effectively. Hypovolemic shock divides into two categories: hemorrhagic and non-hemorrhagic.

Hemorrhagic causes include gastrointestinal bleeding (from peptic ulcers, varices, diverticulosis), traumatic injuries, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms, and spontaneous bleeding in patients on anticoagulants. Non-hemorrhagic causes encompass severe vomiting and diarrhea, excessive diuretic use, burns causing massive fluid loss through damaged skin, diabetic ketoacidosis, and third-spacing of fluids in conditions like pancreatitis or bowel obstruction.

Clinical Presentation: Patients exhibit tachycardia, weak peripheral pulses, cool and clammy skin, delayed capillary refill, orthostatic hypotension, flat jugular veins, and oliguria. Laboratory findings typically show elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN) to creatinine ratio, increased hematocrit in non-hemorrhagic cases, and elevated lactate levels.

Cardiogenic Shock

Cardiogenic shock occurs when the heart cannot pump sufficient blood to meet the body’s metabolic demands despite adequate intravascular volume. This “pump failure” accounts for approximately 5-10% of acute myocardial infarction cases and carries a mortality rate of 50-75%.

Causes include acute myocardial infarction (especially affecting more than 40% of left ventricular muscle), acute valvular dysfunction (ruptured papillary muscle, acute severe mitral or aortic regurgitation), myocarditis, end-stage cardiomyopathy, cardiac tamponade, and severe arrhythmias. Right ventricular infarction represents a unique subset where the right ventricle cannot pump blood through the lungs, causing “backward” failure.

Clinical Presentation: Unlike hypovolemic shock, cardiogenic shock patients often present with signs of fluid overload including pulmonary edema (rales on lung examination, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea), elevated jugular venous pressure, peripheral edema, and an S3 gallop on cardiac auscultation. Patients may also describe chest pain if acute coronary syndrome is the underlying cause.

Distributive Shock (Septic, Anaphylactic, Neurogenic)

Distributive shock is characterized by widespread peripheral vasodilation leading to relative hypovolemia despite normal or even increased intravascular volume. Blood pools in dilated peripheral vessels, reducing effective circulating volume and tissue perfusion. This represents the most common type of shock encountered in medical practice.

Septic Shock: The most frequent form of distributive shock, septic shock is defined as sepsis-induced hypotension requiring vasopressor therapy to maintain MAP ≥65 mmHg and having lactate levels greater than 2 mmol/L despite adequate fluid resuscitation. Septic shock results from a dysregulated host immune response to infection, most commonly from gram-positive bacteria (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus) in the United States. Patients present with fever or hypothermia, tachycardia, tachypnea, altered mental status, warm peripheries in early “warm shock” or cool extremities in late “cold shock,” and signs pointing to the infection source (pneumonia, urinary tract infection, cellulitis, intra-abdominal infection).

Anaphylactic Shock: This life-threatening hypersensitivity reaction occurs within minutes of exposure to an allergen (medications, foods, insect stings, latex). Massive histamine release causes vasodilation and increased capillary permeability. Patients develop hypotension, urticaria, angioedema, bronchospasm (wheezing, stridor), and gastrointestinal symptoms. The 2025 ERC guidelines emphasize immediate intramuscular epinephrine 0.5 mg as first-line treatment, with repeat dosing every 5 minutes if needed.

Neurogenic Shock: Following spinal cord injury (typically above T6 level) or severe brain injury, disruption of autonomic pathways causes loss of sympathetic vascular tone. Unlike other shock types, neurogenic shock presents with hypotension accompanied by bradycardia rather than tachycardia, and warm, dry skin rather than cool, clammy skin. This unique presentation – sometimes called “warm shock with paradoxical bradycardia” – helps clinicians distinguish neurogenic from other shock types.

Obstructive Shock

Obstructive shock results from physical obstruction of blood flow in the cardiovascular system, preventing adequate cardiac output despite normal cardiac function. Common causes include massive pulmonary embolism (blocking right ventricular outflow), tension pneumothorax (compressing the heart and great vessels), cardiac tamponade (fluid in pericardial sac restricting cardiac filling), and constrictive pericarditis.

Clinical Presentation: These conditions often present with specific physical examination findings. Tension pneumothorax shows unilateral absent breath sounds, tracheal deviation away from the affected side, and hyperresonance to percussion. Cardiac tamponade classically demonstrates Beck’s triad: hypotension, muffled heart sounds, and elevated jugular venous pressure, along with pulsus paradoxus (blood pressure drop >10 mmHg during inspiration). Massive pulmonary embolism may present with sudden dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, hypoxemia, and signs of right heart strain on ECG.

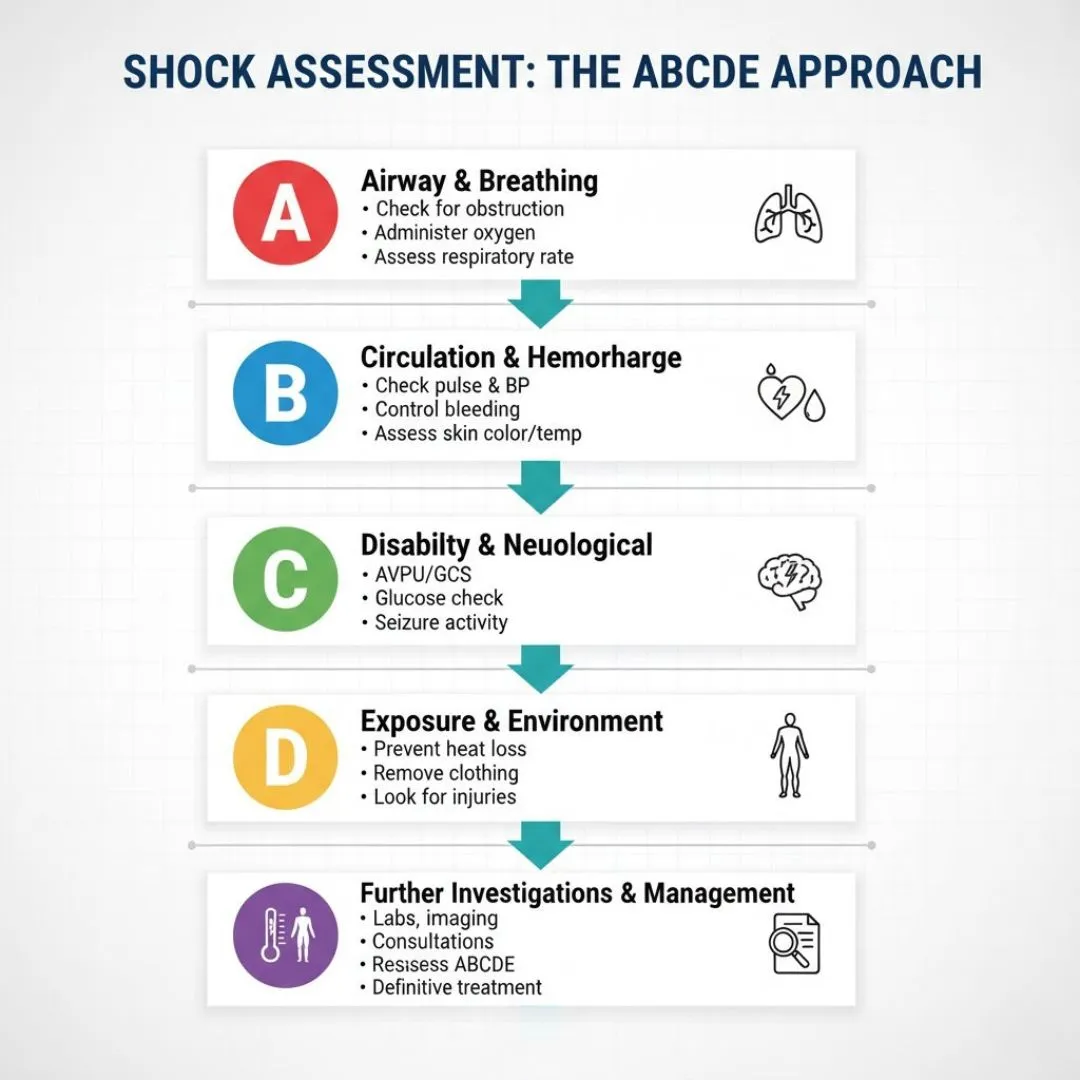

Clinical Assessment of Shock: The ABCDE Approach

The ABCDE approach to shock provides a systematic framework for rapidly assessing and stabilizing critically ill patients. This internationally recognized method ensures that life-threatening problems are identified and addressed in order of priority. The 2025 resuscitation guidelines continue to emphasize this structured approach as the gold standard for initial assessment.

Airway Assessment

Begin every shock assessment by evaluating airway patency. Ask the patient a simple question – if they can speak clearly, the airway is patent. Look for signs of airway obstruction including stridor, inability to speak, drooling, use of accessory muscles, or paradoxical chest/abdominal movement. In unconscious patients, perform a head-tilt chin-lift maneuver (or jaw thrust if cervical spine injury suspected) and inspect the oropharynx for foreign bodies, blood, or vomitus.

Red Flags: Complete airway obstruction, rapidly progressing angioedema (anaphylactic shock), severe altered consciousness with loss of protective airway reflexes. These situations require immediate advanced airway management with endotracheal intubation.

Breathing Evaluation

Assess respiratory rate, depth, pattern, and oxygen saturation. Normal respiratory rate is 12-20 breaths per minute; both tachypnea (>20) and bradypnea (<12) indicate respiratory compromise. Auscultate all lung fields listening for decreased air entry (pneumothorax, pleural effusion), crackles (pulmonary edema in cardiogenic shock), or wheezing (anaphylaxis).

Key Actions: Administer high-flow oxygen (15L via non-rebreather mask) targeting SpO2 >94% in most patients. In shock with respiratory failure, early mechanical ventilation may be necessary, but be aware that positive pressure ventilation can further compromise venous return and worsen hypotension.

Circulation and Hemodynamic Parameters

This represents the core of clinical assessment of shock. Evaluate heart rate, blood pressure, capillary refill time, peripheral pulses, skin temperature and color, and jugular venous pressure. Tachycardia (>100 bpm) is nearly universal in shock as a compensatory mechanism, though neurogenic shock and certain medications can cause relative bradycardia.

Measure blood pressure in both arms; a difference >20 mmHg suggests aortic dissection. Hypotension (SBP <90 mmHg or MAP <65 mmHg) confirms shock but may be absent in early compensated shock. Assess capillary refill time by pressing on the fingernail bed for 5 seconds and counting seconds until color returns; normal is <2 seconds, while >3 seconds indicates poor peripheral perfusion.

Immediate Interventions: Obtain large-bore intravenous access (two 16-18 gauge peripheral IVs or central venous catheter), begin fluid resuscitation with isotonic crystalloids, start continuous cardiac monitoring, and obtain blood samples for laboratory testing.

Disability – Neurological Assessment

Rapidly assess conscious level using the ACVPU scale: Alert, Confused, responds to Voice, responds to Pain, or Unresponsive. Check pupils for size, equality, and reactivity (PEARL – pupils equal and reactive to light). Measure blood glucose immediately as hypoglycemia can mimic shock and altered consciousness.

Altered mental status in shock results from cerebral hypoperfusion and should improve with resuscitation. If confusion worsens despite treatment, consider alternative diagnoses such as stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, or toxic ingestion.

Exposure and Environmental Control

Fully expose the patient to identify hidden injuries, rashes, or bleeding sources, but prevent hypothermia by covering the patient with warm blankets after examination. Hypothermia worsens coagulopathy in hemorrhagic shock and increases mortality in all types.

Check temperature – fever suggests septic shock while hypothermia may indicate severe sepsis, hypothyroidism (myxedema coma), or environmental exposure. Examine for dependent edema, abdominal distension (intra-abdominal bleeding), or surgical scars suggesting previous procedures.

Read More : Approach to Unconscious Patient: Causes, Diagnosis, and Emergency Management

Hemodynamic Parameters and Monitoring

Modern management of shock relies heavily on objective hemodynamic parameters to guide resuscitation. The 2025 guidelines emphasize dynamic rather than static measurements, focusing on markers of tissue perfusion rather than blood pressure alone.

Mean Arterial Pressure (MAP) Targets

Mean arterial pressure represents the average pressure in arteries during one cardiac cycle, calculated as MAP = (SBP + 2×DBP)/3 or MAP = DBP + 1/3(pulse pressure). The 2025 resuscitation guidelines recommend targeting MAP ≥65 mmHg in septic shock and most other shock types. This target balances adequate organ perfusion while avoiding excessive vasopressor use.

Recent research suggests that higher MAP targets (75-85 mmHg) may benefit patients with chronic hypertension or traumatic brain injury, though this increases vasopressor requirements and potential complications. Conversely, permissive hypotension (MAP 50-60 mmHg) is increasingly used in uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock before definitive bleeding control to minimize ongoing blood loss.

Lactate Levels as Prognostic Markers

Serum lactate has emerged as one of the most important shock clinical parameters for risk stratification and resuscitation monitoring. Normal lactate is <2 mmol/L; levels of 2-4 mmol/L indicate mild shock, 4-8 mmol/L moderate shock, and >8 mmol/L severe shock with high mortality risk.

Lactate rises during shock from two mechanisms: anaerobic metabolism producing lactate (type A lactic acidosis) and impaired hepatic clearance due to liver hypoperfusion. Serial lactate measurements (every 2-6 hours) help assess resuscitation adequacy; lactate clearance >10-20% suggests effective treatment, while rising lactate indicates inadequate resuscitation or worsening underlying condition.

The ANDROMEDA-SHOCK trial compared lactate-targeted versus capillary refill time-targeted resuscitation in septic shock, finding that both strategies achieved similar outcomes. This supports using lactate as one among several perfusion markers rather than the sole resuscitation target.

Capillary Refill Time in Shock Assessment

Capillary refill time in shock assessment has gained renewed attention following the 2019 ANDROMEDA-SHOCK trial. This simple bedside test involves applying firm pressure to the fingernail bed for 5 seconds, releasing, and measuring time until color returns. Normal CRT is ≤2 seconds; prolonged CRT (>3 seconds) indicates poor peripheral perfusion.

Recent research in cardiogenic shock demonstrated that early abnormal CRT predicted higher mortality even after adjusting for other hemodynamic parameters. The test offers several advantages: no equipment needed, repeatable, real-time assessment of microcirculatory perfusion. Limitations include inter-observer variability, influence of ambient temperature, and reduced accuracy in patients with peripheral vascular disease.

The 2025 guidelines suggest using CRT as part of a multimodal assessment rather than in isolation. Serial CRT measurements help track resuscitation progress; persistently prolonged CRT despite normalized blood pressure and lactate may indicate ongoing microcirculatory dysfunction requiring different interventions.

Urine Output Monitoring

Urine output serves as a sensitive marker of renal perfusion and overall cardiac output. Normal urine output is ≥0.5 mL/kg/hour; oliguria (<0.5 mL/kg/hour) indicates inadequate renal perfusion in shock. Insert a Foley catheter in shocked patients for accurate hourly urine measurement.

While pursuing target urine output helps guide resuscitation, avoid excessive fluid administration solely to restore urine output, as this risks fluid overload and pulmonary edema. Balance urine output with other perfusion markers (lactate, CRT, mental status, skin perfusion) for comprehensive assessment.

Bedside Ultrasound: The RUSH Protocol

The RUSH protocol (Rapid Ultrasound in Shock and Hypotension) represents a revolutionary advancement in bedside shock assessment using point-of-care ultrasound in shock management. Introduced in 2006, RUSH protocol enables clinicians to rapidly categorize undifferentiated shock into hypovolemic, cardiogenic, distributive, or obstructive etiologies within minutes at the bedside.

RUSH Protocol Components

The RUSH exam systematically evaluates three areas: the “pump” (heart), the “tank” (volume status), and the “pipes” (great vessels). Pump assessment involves cardiac ultrasound views evaluating left ventricular contractility (reduced in cardiogenic shock, hyperdynamic in septic shock), right ventricular size (enlarged in massive pulmonary embolism), and pericardial effusion (tamponade).

Tank assessment examines the inferior vena cava (IVC) for collapsibility; a collapsible IVC (<50% diameter during inspiration) suggests hypovolemia, while a dilated non-collapsible IVC indicates fluid overload or right heart failure. The protocol also includes lung ultrasound looking for B-lines (pulmonary edema), pneumothorax, or pleural effusions.

Pipe assessment scans the aorta for aneurysm or dissection and performs compression ultrasound of leg veins seeking deep vein thrombosis (DVT) as a pulmonary embolism source. Studies show RUSH protocol achieves sensitivity of 0.87 and specificity of 0.98 for shock diagnosis, with obstructive shock showing the highest diagnostic accuracy.

Clinical Applications and Evidence

Research across emergency and critical care settings demonstrates that bedside ultrasound for shock significantly improves diagnostic accuracy and speeds time-to-diagnosis compared to traditional methods. In trauma patients, RUSH protocol shortened diagnosis time versus CT scan or chest X-ray without sacrificing accuracy. A randomized controlled trial in anesthesia showed RUSH-guided management improved intraoperative hemodynamic stability, reduced lactate levels, and shortened hypotension duration.

The main advantage of RUSH lies in evaluating undifferentiated shock where the diagnosis remains unclear despite clinical examination. Limitations include the need for operator training (standardized courses now widely available), difficulty obtaining adequate images in obese patients or those with subcutaneous emphysema, and reduced sensitivity for distributive shock. The 2025 guidelines increasingly recommend POCUS as part of standard shock assessment in centers where trained providers are available.

Initial Management of Shock in Adults

The initial management of shock in adults follows a structured approach emphasizing early recognition, immediate resuscitation, and parallel diagnostic evaluation. Time-critical interventions should never be delayed while searching for the underlying cause – stabilize first, diagnose second.

Hemodynamic Resuscitation Principles

Hemodynamic resuscitation in shock aims to restore tissue perfusion and oxygen delivery to prevent irreversible organ damage. The fundamental principle involves optimizing three determinants of oxygen delivery: cardiac output (preload, contractility, afterload), hemoglobin concentration, and arterial oxygen saturation.

Early goal-directed therapy, pioneered in septic shock research, targets specific physiological endpoints within the first 6 hours: MAP ≥65 mmHg, urine output ≥0.5 mL/kg/hour, central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) ≥70%, and lactate clearance. While rigid protocol adherence is no longer mandated by 2025 guidelines, these endpoints remain useful resuscitation targets.

Fluid Resuscitation Strategies

Intravenous fluid resuscitation forms the cornerstone of shock resuscitation guidelines for hypovolemic, septic, and most other shock types (with important exceptions discussed below). The 2025 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines recommend initial fluid resuscitation with 30 mL/kg of isotonic crystalloid (normal saline or Balanced solutions like Lactated Ringer’s) within 3 hours for septic shock.

Crystalloid versus Colloid Debate: Recent large trials show no mortality benefit for colloids (albumin, hydroxyethyl starch) over crystalloids in most shock situations, with crystalloids being significantly cheaper. Balanced crystalloids (Lactated Ringer’s, Plasma-Lyte) may reduce acute kidney injury compared to normal saline in septic shock, though evidence remains mixed.

Fluid Responsiveness: Not all hypotensive patients need more fluid; approximately 50% of shocked patients are not fluid-responsive. Assess fluid responsiveness using dynamic tests: passive leg raise with cardiac output monitoring, pulse pressure variation (in mechanically ventilated patients), or IVC collapsibility on ultrasound. Avoid fluid overload, which increases mortality through pulmonary edema, abdominal compartment syndrome, and tissue edema impairing oxygen diffusion.

Special Considerations: In cardiogenic shock, aggressive fluid resuscitation can worsen pulmonary edema; give judicious 250 mL boluses with careful reassessment. In obstructive shock from massive pulmonary embolism, excessive fluid paradoxically worsens hypotension by overdistending the failing right ventricle. It requires blood product transfusion (packed red blood cells, plasma, platelets in 1:1:1 ratio) rather than crystalloid alone once ongoing bleeding is identified.

Vasopressor and Inotrope Selection

When fluid resuscitation fails to restore adequate MAP (≥65 mmHg), vasopressor therapy becomes necessary. Norepinephrine is the first-line vasopressor for septic, neurogenic, and most other shock types according to 2025 guidelines. Norepinephrine combines alpha-1 adrenergic effects (vasoconstriction) with modest beta-1 effects (increased cardiac contractility), effectively raising blood pressure with minimal tachycardia.

Vasopressin (0.03-0.04 units/minute) is added as a second-line agent if norepinephrine doses exceed 0.5 mcg/kg/min or as a norepinephrine-sparing strategy. Vasopressin acts through V1 receptors causing vasoconstriction without increasing heart rate. Epinephrine serves as a third-line option in refractory shock, though it increases lactate levels (from beta-2 receptor stimulation of glycolysis) independent of tissue hypoxia, potentially confusing assessment.

Phenylephrine (pure alpha-1 agonist) is reserved for specific situations like neurogenic shock where tachycardia must be avoided, though it may reduce cardiac output through increased afterload. Dobutamine (beta-1 agonist inotrope) is used in cardiogenic shock to increase contractility when cardiac output remains low despite adequate preload, though it may cause hypotension through vasodilation.

All vasopressors require central venous access and continuous cardiac monitoring. Titrate to MAP target (usually 65 mmHg) rather than fixed doses, and wean as soon as safely possible to avoid complications including arrhythmias, tissue ischemia, and limb gangrene.

Read More : Heart Failure: Classification, Diagnosis & Notes

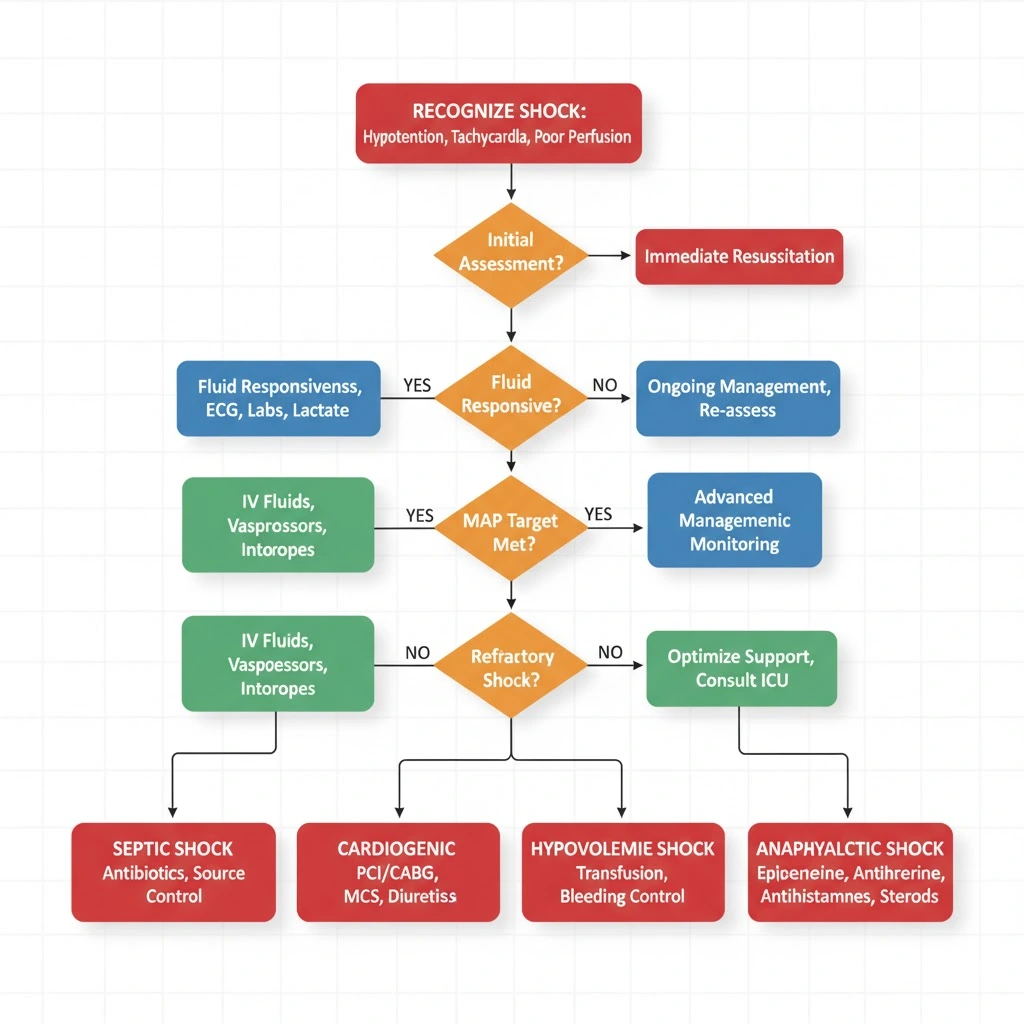

Algorithm for Shock Management: Step-by-Step Approach

This algorithm for shock management provides a systematic approach to undifferentiated shock applicable in emergency departments, ICUs, and general wards.

Step 1: Recognize Shock

- Hypotension (SBP <90 or MAP <65 mmHg) PLUS

- Signs of hypoperfusion (altered mental status, oliguria, cool extremities, prolonged CRT, elevated lactate >2 mmol/L)

2: Immediate Resuscitation (First 5 Minutes)

- Call for help/activate rapid response team

- Ensure patent airway, give high-flow oxygen

- Obtain large-bore IV access (2 x 18G peripheral or central line)

- Begin fluid resuscitation: 500-1000 mL crystalloid rapid bolus

- Continuous monitoring: cardiac monitor, pulse oximetry, blood pressure

- Draw blood: CBC, electrolytes, creatinine, lactate, blood cultures, coagulation studies

- 12-lead ECG, portable chest X-ray

3: Classify Shock Type

- Hypovolemic: History of bleeding/fluid loss, flat JVP, orthostatic hypotension

- Cardiogenic: Chest pain, elevated JVP, pulmonary edema, low cardiac output on echo

- Distributive: Fever (sepsis), urticaria (anaphylaxis), spinal injury (neurogenic)

- Obstructive: Unilateral absent breath sounds (tension pneumothorax), Beck’s triad (tamponade), pleuritic chest pain with hypoxia (PE)

- Consider RUSH ultrasound if diagnosis unclear

4: Type-Specific Treatment

- Hypovolemic: Stop bleeding, transfuse blood products, continue IV fluids

- Cardiogenic: Reduce preload (diuretics), increase contractility (inotropes), consider reperfusion (PCI for STEMI)

- Septic: Source control, antibiotics within 1 hour, 30 mL/kg fluid, vasopressors if needed

- Anaphylactic: IM epinephrine 0.5 mg (repeat q5 min), IV fluids, antihistamines, steroids

- Obstructive: Specific intervention (needle decompression for tension pneumothorax, pericardiocentesis for tamponade, thrombolysis for massive PE)

5: Vasopressor Support (if MAP <65 despite fluids)

- Start norepinephrine 0.05-0.5 mcg/kg/min, titrate to MAP ≥65

- Add vasopressin 0.03 units/min if inadequate response

- Consider epinephrine if refractory

6: Reassess and Monitor

- Serial lactate q2-4 hours (target clearance >10%)

- Urine output q1 hour (target >0.5 mL/kg/hr)

- Mental status, skin perfusion, capillary refill

- Avoid fluid overload: assess fluid responsiveness before additional boluses

7: Definitive Treatment and ICU Transfer

- Arrange ICU admission for vasopressor-dependent shock

- Definitive treatment for underlying cause (surgery for bleeding, PCI for MI, drainage for abscess)

- Organ support as needed (mechanical ventilation, renal replacement therapy)

Type-Specific Management Protocols

Hypovolemic Shock Management

Hemorrhagic Shock:

The management of shock from hemorrhage focuses on bleeding control and blood product resuscitation. Activate massive transfusion protocol early in major hemorrhage. Transfuse packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets in 1:1:1 ratio to prevent dilutional coagulopathy. Target hemoglobin 7-9 g/dL (restrictive strategy) unless active coronary ischemia present.

Permissive hypotension (SBP 80-90 mmHg) is used before surgical bleeding control to minimize blood loss and avoid “popping the clot”. Once bleeding is controlled, target normal MAP. Damage control surgery involves rapid control of bleeding and contamination, temporary closure, ICU resuscitation, and delayed definitive repair. Tranexamic acid (1g IV over 10 minutes, then 1g over 8 hours) reduces mortality when given within 3 hours of traumatic injury.

Non-hemorrhagic Hypovolemic Shock:

Aggressive crystalloid resuscitation (2-4 liters initially) with ongoing reassessment. Identify and correct underlying cause: antiemetics and fluid replacement for gastroenteritis, insulin and fluids for diabetic ketoacidosis, cooling measures for heat stroke. Monitor electrolytes closely as rapid fluid shifts can cause dangerous imbalances.

Cardiogenic Shock Management

Cardiogenic shock management aims to increase cardiac output while reducing myocardial oxygen demand. Reduce preload with diuretics (furosemide 40-80 mg IV) if pulmonary edema present, but avoid aggressive diuresis that worsens hypotension. Increase contractility with inotropes: dobutamine (2.5-20 mcg/kg/min) is first-line, though it may worsen hypotension through vasodilation requiring concurrent norepinephrine.

Mechanical circulatory support includes intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) for temporary support, particularly in MI-related cardiogenic shock awaiting revascularization. More advanced devices (Impella, ECMO) are increasingly used in refractory cases at specialized centers. Reperfusion is critical in acute MI: immediate PCI or thrombolysis within 90 minutes of presentation dramatically improves outcomes.

Avoid excessive fluid administration – give small boluses (250 mL) with careful reassessment. Consider pulmonary artery catheter placement for hemodynamic monitoring in complex cases. Treat arrhythmias promptly: synchronized cardioversion for unstable tachyarrhythmias, transcutaneous pacing for symptomatic bradycardia.

Septic Shock Management

The emergency management of shock in sepsis follows the Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundles. Hour 1 Bundle includes: measure lactate (remeasure if >2 mmol/L), obtain blood cultures before antibiotics, administer broad-spectrum antibiotics within 1 hour, begin rapid fluid resuscitation with 30 mL/kg crystalloid if hypotensive or lactate ≥4 mmol/L, and apply vasopressors if hypotension persists after fluid resuscitation.

Antibiotic selection should cover likely pathogens based on suspected source: anti-pseudomonal beta-lactam (piperacillin-tazobactam, meropenem, cefepime) plus vancomycin for most hospital-acquired infections; ceftriaxone for community-acquired pneumonia. Delay in appropriate antibiotics increases mortality by 7.6% per hour.

Source control – drain abscesses, remove infected devices, debride necrotic tissue – is essential and should be accomplished within 6-12 hours when feasible. Vasopressor target: MAP ≥65 mmHg using norepinephrine first-line. Adjunctive therapies: Consider hydrocortisone 200 mg/day if shock remains refractory despite adequate fluids and vasopressors.

Neurogenic Shock Management

Neurogenic shock management differs importantly from other types due to loss of sympathetic tone. Fluid resuscitation is necessary but use caution – neurogenic shock patients have lost vasomotor tone but retain normal intravascular volume, so excessive fluids cause pulmonary edema. Give smaller boluses (500 mL) with frequent reassessment.

Vasopressor selection: Norepinephrine or dopamine are preferred as they provide both vasoconstrictive and chronotropic effects, countering both the hypotension and bradycardia characteristic of neurogenic shock. Target MAP 85-90 mmHg in spinal cord injury to maintain spinal cord perfusion. Spinal cord protection: Maintain normothermia, avoid hypoxia, and early neurosurgical consultation for decompression if indicated.

Bradycardia management: Atropine 0.5-1 mg IV or transcutaneous pacing if hemodynamically significant. Prevention of complications – DVT prophylaxis, stress ulcer prophylaxis, skin care, and bowel/bladder management – is crucial given prolonged immobility.

Read More : Complete Blood Count Interpretation: Red Flags, Clinical Correlates & Exam Caselets

Latest Guidelines in Resuscitation (2025 Updates)

- The shock resuscitation guidelines have evolved significantly with the 2025 European Resuscitation Council and American Heart Association updates, incorporating recent high-quality trial evidence.

- Fluid Resuscitation: The 2025 guidelines emphasize restrictive fluid strategies after initial resuscitation, recognizing that fluid overload worsens outcomes. Dynamic assessment of fluid responsiveness is preferred over static targets (CVP, PAOP). Balanced crystalloids are suggested over normal saline in septic shock to reduce hyperchloremic acidosis and potential AKI, though this remains a weak recommendation.

- Vasopressor Therapy: Norepinephrine remains the undisputed first-line vasopressor across all types requiring vasopressor support. The 2025 guidelines suggest early vasopressor initiation (within first hour) rather than delaying until after large fluid volumes, as this may reduce fluid overload without worsening outcomes. Vasopressin as a second-line agent shows mortality benefits in some analyses.

- Septic Shock Updates: The “Golden Hour” concept is reinforced – antibiotic administration within 1 hour of septic shock recognition is a performance measure. Source control timing recommendations clarify that drainage should occur “as soon as possible” within 6-12 hours when feasible. Procalcitonin-guided antibiotic de-escalation is increasingly recommended to reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure.

- Cardiogenic Shock: The 2025 guidelines emphasize early consideration of mechanical circulatory support in appropriate patients rather than prolonging inotrope trials. Door-to-balloon time for STEMI complicated by cardiogenic shock should be <60 minutes. Pulmonary artery catheter use is suggested in refractory cardiogenic shock to guide therapy, reversing prior recommendations against routine use.

- Point-of-Care Ultrasound: The RUSH protocol and focused cardiac ultrasound receive stronger endorsements in 2025 guidelines, with recommendations for training emergency and critical care physicians in POCUS. This reflects growing evidence that bedside ultrasound improves diagnostic accuracy and speeds appropriate treatment.

- Anaphylaxis Management: The 2025 ERC guidelines maintain IM epinephrine 0.5 mg as the immediate first-line intervention, repeating every 5 minutes if needed. They emphasize early IV crystalloid fluid boluses (potentially 4-6 liters needed) and clarify that antihistamines and steroids are adjunctive only, not primary treatments.

Common Mistakes to Avoid in Shock Management

Learning from common errors can dramatically improve shock management outcomes.

#1: Attributing hypotension to “pre-existing conditions” without recognizing new-onset shock. Patients with chronic conditions like heart failure or COPD can develop superimposed shock requiring aggressive intervention.

#2: Waiting for hypotension before intervening. It exists in the compensated phase before blood pressure drops; tachycardia, altered mental status, oliguria, and elevated lactate mandate early treatment.

#3: Excessive crystalloid administration without assessing fluid responsiveness, leading to pulmonary edema, abdominal compartment syndrome, and worse outcomes.

#4: Delaying vasopressors until after massive fluid volumes have been given. Current guidelines support earlier vasopressor initiation once hypotension persists after initial 1-2 liter fluid bolus.

#5: Choosing wrong vasopressor – using dopamine (which causes more arrhythmias) or phenylephrine (which decreases cardiac output) instead of norepinephrine first-line.

#6: Missing obstructive shock because tension pneumothorax and cardiac tamponade are immediately life-threatening and require specific interventions (needle decompression, pericardiocentesis) that fluid and vasopressors won’t fix.

#7: Antibiotic delay in septic shock – every hour delay increases mortality significantly; give antibiotics within 1 hour.

#8: Ignoring lactate clearance as a resuscitation endpoint. Persistently elevated lactate despite normalized blood pressure indicates ongoing tissue hypoxia requiring reassessment of shock type and treatment adequacy.

#9: Undertreating pain and anxiety, which increase metabolic demand and oxygen consumption, worsening shock.

#10: Failing to reassess frequently. Shock is dynamic; clinical status can deteriorate rapidly. Reassess vital signs, mental status, urine output, and lactate every 15-30 minutes initially, adjusting treatment accordingly.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q : What is the most common type of shock?

A : Distributive shock, particularly septic shock, is the most common type encountered in clinical practice, accounting for approximately 60% of shock cases in ICUs. Septic shock carries a 40-50% mortality rate despite modern treatment advances.

Q : How do you differentiate between the different types of shock?

A : Clinical history, physical examination, and hemodynamic parameters help differentiate shock types. Hypovolemic shock presents with flat neck veins and history of fluid loss; cardiogenic shows elevated JVP and pulmonary edema; distributive demonstrates warm peripheries initially with infection signs; obstructive reveals specific findings like unilateral breath sounds (pneumothorax) or Beck’s triad (tamponade). Bedside ultrasound using the RUSH protocol rapidly distinguishes shock types.

Q : What is the target blood pressure in shock resuscitation?

A : The target mean arterial pressure (MAP) is ≥65 mmHg for most types according to 2025 guidelines. Higher targets (MAP 75-85 mmHg) may benefit patients with chronic hypertension or traumatic brain injury, while permissive hypotension (MAP 50-60 mmHg) is used in uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock before surgical control.

Q : When should you start vasopressors in shock?

A : Start vasopressors when hypotension (MAP <65 mmHg) persists after initial fluid resuscitation (1-2 liters crystalloid). The 2025 guidelines support earlier vasopressor initiation rather than delaying until massive fluid volumes have been administered, which may reduce fluid overload complications.

Q : What is the best fluid for shock resuscitation?

A : Isotonic crystalloids (normal saline or balanced solutions like Lactated Ringer’s) are recommended for initial resuscitation in most shock types. Balanced crystalloids may reduce acute kidney injury compared to normal saline in septic shock. It requires blood product transfusion (PRBCs, plasma, platelets in 1:1:1 ratio) rather than crystalloid alone.

Q : What is lactate clearance and why does it matter?

A : Lactate clearance refers to the percentage decrease in serum lactate over time (typically measured every 2-6 hours). Clearance >10-20% indicates effective resuscitation, while persistently elevated or rising lactate suggests inadequate treatment. Lactate is both a marker of tissue hypoxia and an independent predictor of mortality in shock.

Q : Can you have shock without hypotension?

A : Yes, compensated shock occurs when the body’s compensatory mechanisms (tachycardia, vasoconstriction, increased cardiac contractility) maintain blood pressure despite inadequate tissue perfusion. Signs include tachycardia, altered mental status, oliguria, cool extremities, prolonged capillary refill, and elevated lactate even with normal blood pressure. Early recognition and treatment of compensated shock prevents progression to decompensated shock.

Exam Questions & Answers (University Pattern)

Question 1: Short Answer Question (10 Marks)

Stem: A 65-year-old man presents to the emergency department with a 2-day history of productive cough, fever, and confusion. On examination: BP 85/50 mmHg, HR 125/min, RR 32/min, temperature 39.2°C, SpO2 88% on room air. Chest examination reveals crackles in the right lower lobe. Laboratory results show WBC 18,000/μL, lactate 4.5 mmol/L, creatinine 2.1 mg/dL.

a) What type of shock is this patient experiencing? Justify your answer. (2 marks)

b) List the immediate management steps you would take in the first hour. (5 marks)

c) What are the target endpoints for resuscitation in this patient? (3 marks)

Model Answer:

a) Septic shock (1 mark). Justified by: hypotension with infection source (pneumonia – fever, productive cough, crackles), elevated lactate >2 mmol/L, signs of organ dysfunction (acute kidney injury, altered mental status), and evidence of distributive shock (warm peripheries would be noted on exam) (1 mark).

b) Immediate management (Hour 1 Bundle):

- Administer high-flow oxygen targeting SpO2 >94% (1 mark)

- Obtain large-bore IV access, draw blood cultures before antibiotics (1 mark)

- Administer broad-spectrum antibiotics within 1 hour (e.g., ceftriaxone + azithromycin for community-acquired pneumonia) (1 mark)

- Begin aggressive fluid resuscitation with 30 mL/kg (approximately 2-2.5 liters) isotonic crystalloid rapidly (1 mark)

- If hypotension persists after fluid bolus, initiate norepinephrine via central line targeting MAP ≥65 mmHg (1 mark)

c) Target endpoints for resuscitation:

- Mean arterial pressure ≥65 mmHg (1 mark)

- Urine output ≥0.5 mL/kg/hour (1 mark)

- Lactate clearance >10% on repeat measurement in 2-6 hours (1 mark)

Quick Diagram Prompt: “Create a flowchart showing septic shock management from recognition through initial resuscitation and organ support, 800x600px, simple arrows and boxes.”

Viva Tips:

- Be prepared to explain why antibiotics must be given within 1 hour (mortality increases 7.6% per hour delay)

- Know the difference between SIRS and sepsis definitions

- Understand why norepinephrine is preferred over dopamine

- Be able to discuss lactate elevation mechanisms in sepsis

Last-Minute Checklist:

✓ Septic shock = sepsis + hypotension + lactate >2 despite fluids

✓ Hour 1 Bundle: cultures, antibiotics, fluids, vasopressors

✓ 30 mL/kg fluid bolus first-line

✓ Norepinephrine first-line vasopressor

✓ MAP target ≥65 mmHg

Question 2: Long Answer Question (20 Marks)

Stem: Discuss the classification, pathophysiology, clinical features, and management of cardiogenic shock. Include the role of mechanical circulatory support devices.

Model Answer:

Definition (2 marks):

Cardiogenic shock is a state of inadequate tissue perfusion due to primary cardiac dysfunction (pump failure), characterized by sustained hypotension (SBP <90 mmHg or MAP <65 mmHg for >30 minutes), signs of tissue hypoperfusion, and cardiac index <2.2 L/min/m² with adequate or elevated left ventricular filling pressure (PCWP >15 mmHg).

Classification/Causes (3 marks):

- Myocardial causes: Acute myocardial infarction (>40% LV involvement), acute myocarditis, end-stage cardiomyopathy, myocardial contusion

- Mechanical causes: Acute valvular dysfunction (papillary muscle rupture, acute severe MR/AR), ventricular septal rupture post-MI, free wall rupture

- Arrhythmic causes: Sustained ventricular tachycardia, severe bradyarrhythmias, heart blocks

Pathophysiology (4 marks):

Primary myocardial dysfunction → decreased stroke volume and cardiac output → compensatory tachycardia and peripheral vasoconstriction → increased myocardial oxygen demand and decreased coronary perfusion (especially subendocardial) → further myocardial ischemia → progressive pump failure (vicious cycle). Activation of neurohormonal systems (RAAS, SNS) causes fluid retention and increased afterload, worsening cardiac function. Cellular hypoxia leads to anaerobic metabolism, lactate accumulation, and metabolic acidosis, further depressing myocardial contractility.

Clinical Features (3 marks):

- Symptoms: Chest pain (if ACS), dyspnea, orthopnea, altered mental status, oliguria

- Signs: Hypotension, tachycardia, pulmonary crackles (pulmonary edema), elevated JVP, S3 gallop, cool and clammy peripheries, peripheral edema, narrow pulse pressure

- Laboratory: Elevated troponin/CK-MB (if MI), elevated BNP, elevated lactate, metabolic acidosis, elevated creatinine (cardiorenal syndrome)

Management (6 marks):

-

Initial stabilization: High-flow oxygen, mechanical ventilation if respiratory failure, IV access, continuous monitoring

-

Hemodynamic optimization:

-

Reduce preload: Judicious diuretics (furosemide 40-80 mg IV) if pulmonary edema, but avoid excessive diuresis worsening hypotension

-

Increase contractility: Inotropes – dobutamine 2.5-20 mcg/kg/min first-line; add norepinephrine if concurrent hypotension

-

Cautious fluid administration: Small boluses (250 mL) only if evidence of hypovolemia

-

-

Treat underlying cause:

-

Immediate reperfusion for STEMI (PCI within 90 minutes or thrombolysis)

-

Arrhythmia management: cardioversion, pacing, antiarrhythmics

-

Surgical consultation for mechanical complications (valve repair/replacement, VSD closure)

-

-

Mechanical circulatory support (discussed below)

-

Organ support: Renal replacement therapy if needed, mechanical ventilation, nutritional support

Mechanical Circulatory Support (2 marks):

- Intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP): Inflates during diastole (improving coronary perfusion) and deflates during systole (reducing afterload); provides modest hemodynamic support as bridge to definitive therapy

- Percutaneous ventricular assist devices: Impella (continuous axial flow pump), TandemHeart; provide greater circulatory support than IABP

- Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): VA-ECMO for refractory cardiogenic shock; provides both cardiac and respiratory support

- Indications: Persistent hypotension despite optimal medical therapy, bridge to recovery, transplant, or durable VAD

Quick Diagram Prompt: “Create a detailed pathophysiology flowchart of cardiogenic shock showing the vicious cycle from myocardial dysfunction to progressive pump failure, 1000x700px, include compensatory mechanisms and end-organ effects.”

Viva Tips:

- Differentiate cardiogenic from other shock types using JVP and lung findings

- Explain why IABP inflates in diastole and deflates in systole

- Discuss why excessive fluids worsen cardiogenic shock (pulmonary edema)

- Be prepared to interpret Swan-Ganz catheter data (high PCWP, low CO)

Last-Minute Checklist:

✓ Cardiogenic shock = pump failure + low CO + high filling pressures

✓ Clinical triad: hypotension + pulmonary edema + elevated JVP

✓ Dobutamine increases contractility (first-line inotrope)

✓ IABP: inflates diastole, deflates systole

✓ Immediate PCI for STEMI with cardiogenic shock

Conclusion

Management of Shock: Types, Clinical Assessment, and Latest Guidelines in Resuscitation represents a critical lifesaving skill that every medical professional must master. This comprehensive guide has explored how types of shock—hypovolemic, cardiogenic, distributive, and obstructive—each require rapid recognition using the ABCDE approach to shock and targeted interventions based on hemodynamic resuscitation principles. The 2025 shock resuscitation guidelines emphasize early vasopressor use, restrictive fluid strategies, and point-of-care ultrasound with the RUSH protocol for undifferentiated shock.

For MBBS students, understanding emergency management of shock builds essential exam competence and clinical skills. The difference between survival and death lies in those critical first hours—recognizing compensated shock early and implementing evidence-based management of shock protocols immediately.

Subscribe to Simply MBBS newsletter for regular updates on emergency medicine protocols and exam preparation. Visit simplymbbs.com to explore more lifesaving medical education content designed for students and healthcare professionals worldwide.