Snakebite envenomation is a significant yet often overlooked medical emergency worldwide. Among the diverse spectrum of venomous snakes, neurotoxic species such as cobras, kraits, coral snakes, and mambas possess toxins that specifically target the neuromuscular junction, resulting in progressive muscle paralysis. This paralysis can swiftly affect respiratory muscles, leading to respiratory failure and, if untreated, death. Understanding Neuroparalytic Snake Bite is crucial for MBBS students preparing for examinations, emergency doctors making split-second decisions, allied health professionals managing supportive care, and laypersons seeking to recognize early warning signs.

In this comprehensive article, we explore:

- Definition and global epidemiology

- Regional incidence nuances in the USA and India

- Pathophysiological mechanisms at the molecular level

- Clinical features from early ocular signs to life-threatening respiratory arrest

- Diagnostic strategies, including point-of-care tests and electrodiagnostics

- Evidence-based treatment protocols tailored to resource settings

- Comparative analysis with hemotoxic and cytotoxic envenomation

- Expert insights, data-driven statistics, and real-life case studies

- Common pitfalls and mistakes in management

- Frequently asked questions with clear, concise answers

- University-style exam questions with model answers, diagram prompts, and viva tips

By the end of this guide, readers will have a thorough understanding of Neuroparalytic Snake Bite, empowering them to make informed decisions, improve patient outcomes, and excel academically.

What Is Neuroparalytic Snake Bite?

Definition:

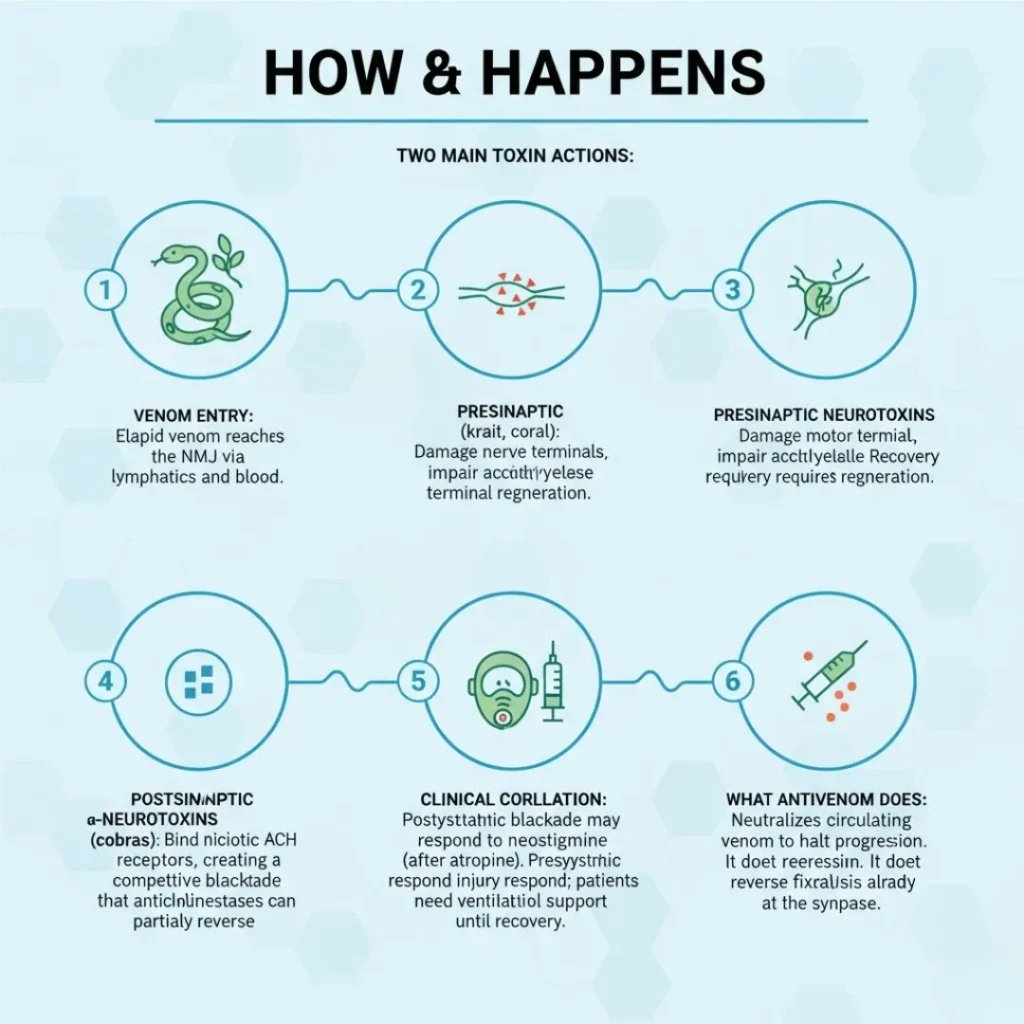

A neuroparalytic snakebite occurs when the venom of certain snakes disrupts normal neuromuscular transmission. This occurs through two primary toxin classes:

- Presynaptic neurotoxins (e.g., β-bungarotoxin) that irreversibly damage the presynaptic nerve terminal, depleting acetylcholine vesicles and impairing neurotransmitter release.

- Postsynaptic neurotoxins (e.g., α-neurotoxin) that competitively bind to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on the motor endplate, preventing acetylcholine from depolarizing the muscle fiber.

Global Epidemiology:

Annually, more than 2.5 million snakebite envenomations occur worldwide, resulting in over 100,000 fatalities. Neurotoxic bites account for a disproportionate share of mortality in South and Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Latin America.

Why Neuroparalytic Snake Bite Matters

For MBBS Students

- Grasping the molecular basis of neuromuscular blockade helps in understanding other neuromuscular disorders.

- Exam-oriented Q&A improves recall and application in viva voce and written tests.

For Doctors & Allied Health Professionals

- Rapid recognition and protocol-driven management reduce ICU days and healthcare costs.

- Familiarity with regional antivenom availability and dosing ensures optimal resource utilization.

General Public & Medical Enthusiasts

- Early symptom awareness leads to timely medical attention, minimizing complications.

- Dispels myths surrounding snakebite first aid and civilian management.

Epidemiology and Species Distribution

India: High-Burden Regions

-

Annual Incidence: 100,000–150,000 envenomations; up to 50,000 deaths.

-

Key Neurotoxic Species:

-

Indian cobra (Naja naja)

-

Common krait (Bungarus caeruleus)

-

King cobra (Ophiophagus hannah)

-

-

Risk Factors: Agricultural workers, nighttime outdoor activities, rural settings lacking immediate healthcare access.

USA: Rare but Critical

- Annual Incidence: Approximately 8,000 venomous bites; <200 neurotoxic cases.

- Key Neurotoxic Species: Eastern and Western coral snakes (Micrurus fulvius, Micrurus tener)

- Risk Factors: Outdoor enthusiasts, accidental encounters.

- Mortality: <1% with timely antivenom; higher without rapid transport to specialized centers.

Key Points on Neuroparalytic Snake Bite

- Toxin Action Mechanisms:

Presynaptic toxins: irreversible nerve terminal damage.

Postsynaptic toxins: receptor blockade. - Onset: Symptoms often appear within 30–60 minutes post-bite but can be delayed up to several hours, especially with kraits.

- Early Signs: Ptosis, diplopia, facial muscle weakness.

- Progression: From ocular to bulbar muscles, then trunk and limb muscles, culminating in diaphragmatic paralysis.

- Definitive Treatment: Species-specific or polyvalent antivenom combined with ventilatory support.

- Misdiagnosis Risks: Stroke, myasthenia gravis, botulism—critical delays can increase mortality.

Pathophysiology: Molecular to Systemic

Presynaptic Neurotoxins

- Composed of phospholipase A₂ enzymes (β-bungarotoxin).

- Bind presynaptic membranes, hydrolyzing phospholipids and causing vesicle depletion.

- Leads to reduced acetylcholine release, irreversible until new nerve terminals regenerate over days to weeks.

Postsynaptic Neurotoxins

- Polypeptide chains (α-neurotoxins) that mimic acetylcholine structure.

- High affinity for nicotinic receptors on motor endplate.

- Competitive inhibition prevents muscle fiber depolarization; reversal requires antivenom to displace toxins.

Systemic Distribution

- Venom enters lymphatic circulation, reaching bloodstream within minutes.

- High vascularity of muscle and respiratory centers accelerates toxin delivery to neuromuscular junctions.

Clinical Correlation

- Early ocular muscles involvement due to high neuromuscular junction density.

- Diaphragm and intercostal muscle paralysis directly correlate with mortality risk.

Clinical Presentation & Recognition

First – Stage I (Early/Prodromal)

- Ocular Signs: Ptosis (bilateral eyelid drooping), ophthalmoplegia, diplopia.

- Facial Weakness: Difficulty in smiling or frowning.

Stage II (Bulbar Involvement)

- Dysphagia: Difficulty swallowing; risk of aspiration.

- Dysarthria: Slurred speech; difficulty in articulation.

- Salivation & Dysphonia: Nasal tone, drooling.

Stage III (Generalized Muscle Weakness)

- Limb Weakness: Symmetric, proximal more than distal.

- Neck Flexor Weakness: Inability to lift head.

- Respiratory Distress: Tachypnea, use of accessory muscles.

Final – Stage IV (Respiratory Failure)

- Hypoxia: SpO₂ <90%, cyanosis.

- Hypercapnia: Rising PaCO₂, leading to drowsiness, coma.

- Cardiac Complications: Bradycardia, hypotension due to autonomic involvement.

Diagnostic Evaluation

History & Physical Examination

- Bite History: Time, location, identifiable fang marks.

- Symptom Timeline: Onset and progression of ocular and bulbar signs.

Point-of-Care Tests

-

20-Minute Whole Blood Clotting Test (WBCT):

-

Draw 2 mL venous blood into a glass tube; leave undisturbed for 20 minutes.

-

Neurotoxic bites often yield normal clotting; abnormal WBCT suggests hemotoxic components.

-

Laboratory Investigations

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Baseline for infection, anemia.

- Coagulation Profile: PT, aPTT typically normal in pure neurotoxic envenomation.

- Serum Electrolytes & Renal Function: Assess systemic impact and guide fluid management.

Electrophysiological Studies

- Repetitive Nerve Stimulation (RNS): Shows decremental response (>10% drop) characteristic of neuromuscular junction disorders.

- Single-Fiber EMG: Increased jitter and blocking; rarely used in acute settings.

Imaging

- Chest X-Ray: Evaluate for aspiration pneumonia in bulbar paralysis; monitor endotracheal tube placement.

- Ultrasound: Limited role; may assess local swelling or compartment syndrome.

Treatment Protocols

Pre-Hospital First Aid

-

Calm Reassurance: Reduces heart rate and systemic venom spread.

-

Limb Immobilization: Splint at heart level; avoid elevation to slow lymphatic flow.

-

Avoid Harmful Practices:

-

No tourniquets; risk of ischemia.

-

No incision or suction; risk of infection and increased local tissue damage.

-

-

Rapid Transport: Aim for specialized center with antivenom and ventilation facilities.

Emergency Department Management

Airway, Breathing, Circulation (ABCs)

-

Continuous Monitoring: Pulse oximetry, capnography, vital signs.

-

Early Intubation: Indications:

-

SpO₂ <90% despite supplemental oxygen.

-

Rising PaCO₂ on blood gas analysis.

-

Bulbar muscle weakness with aspiration risk.

-

-

Mechanical Ventilation: Pressure-controlled mode to prevent barotrauma; settings adjusted per blood gas targets.

Antivenom Therapy

Antivenom Selection:

- USA (Coral Snake): Monovalent equine-derived antivenom; initial 3–5 mL IV; repeat based on symptom resolution.

- India (Cobra/Krait): Polyvalent equine-derived antivenom covering “Big Four” snakes; 100 mL IV infusion over 1 hour; guided by clinical response and 20-minute WBCT.

Premedication: Hydrocortisone 100–200 mg IV and antihistamines (chlorpheniramine 10 mg IV) if prior serum sickness or anaphylaxis risk.

Adverse Reaction Management:

- Anaphylaxis: Epinephrine 0.3–0.5 mg IM; supportive IV fluids; airway management.

- Serum Sickness: Occurs 5–10 days post-treatment; treat with steroids and antihistamines.

Supportive Care

- Fluid Management: Maintain euvolemia; isotonic crystalloids; monitor urine output >0.5 mL/kg/hr.

- Atropine: Reserved for cholinergic symptoms (salivation, bronchorrhea).

- Physiotherapy: Early passive movements to prevent joint contractures and muscle atrophy.

- Nutrition: Early enteral feeding via nasogastric tube if ventilated; high-protein diet to support recovery.

- Electrolyte Correction: Regular monitoring and correction of potassium, magnesium, calcium.

Comparative Analysis: Neurotoxic vs. Hemotoxic vs. Cytotoxic Envenomation

| Aspect | Neurotoxic Bite | Hemotoxic Bite | Cytotoxic Bite |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Neuromuscular junction blockade | Coagulation cascade activation, endothelial damage | Local tissue necrosis, compartment syndrome |

| Early Clinical Features | Ptosis, diplopia, dysphagia | Bleeding gums, hematuria, ecchymoses | Severe pain, swelling, blistering, necrosis |

| Laboratory Findings | Normal PT, aPTT, fibrinogen | Prolonged PT, aPTT; low fibrinogen; elevated D-dimer | Possible elevated CK if muscle necrosis |

| First Aid | Immobilize limb, rapid transport | Pressure immobilization bandage, rapid transport | Clean wound, tetanus prophylaxis, surgical consult if needed |

| Antivenom | Species-specific or polyvalent; ventilatory support | Antivenom + blood products (FFP, cryoprecipitate) | Antivenom + early surgical debridement |

| Supportive Measures | Mechanical ventilation, physiotherapy | Blood transfusion, clotting factor replacement | Wound care, analgesia, fasciotomy if compartment syndrome |

| Mortality | High without ventilation (>50%) | High due to hemorrhage and DIC | Morbidity from tissue loss; rare systemic death if untreated |

| Recovery Time | Days to weeks | Days with reversal of coagulopathy | Weeks to months depending on debridement and grafting |

Expert Insights & Data-Driven Points

- The World Health Organization designated snakebite as a neglected tropical disease, urging global alliances to improve antivenom access and training programs.

- A multicenter Indian study reported a median ventilation duration of 72 hours for cobra bites and 96 hours for krait bites, emphasizing resource needs in rural hospitals.

- In the USA, delayed coral snake antivenom administration (>6 hours) correlated with longer ICU stays and increased respiratory complications.

Real-Life Case Studies

Case Study 1: Rural India—Indian Cobra Bite

Patient Profile: 28-year-old male agricultural worker

Timeline & Presentation:

- 45 minutes post-bite: bilateral ptosis, diplopia.

- 90 minutes: dysphagia, generalized weakness.

- 2 hours: respiratory distress (SpO₂ 82%).

Management:

- 100 mL polyvalent antivenom IV over 1 hour.

- Early intubation and ventilation.

- Physiotherapy and enteral feeding initiated on day 2.

Outcome:

- Successfully extubated on day 4.

- Full neuromuscular recovery by day 7; discharged on day 10.

Case Study 2: Suburban USA—Coral Snake Encounter

Patient Profile: 35-year-old hiker

Timeline & Presentation:

- 1 hour post-bite: perioral numbness, blurred vision.

- 3 hours: mild dysphagia; stable vitals.

Management:

- 5 mL equine antivenom bolus; repeat 3 mL after 4 hours due to persistent diplopia.

- Supplemental oxygen; no mechanical ventilation required.

Outcome:

- Resolution of symptoms by 36 hours.

- Discharged with outpatient neurology follow-up.

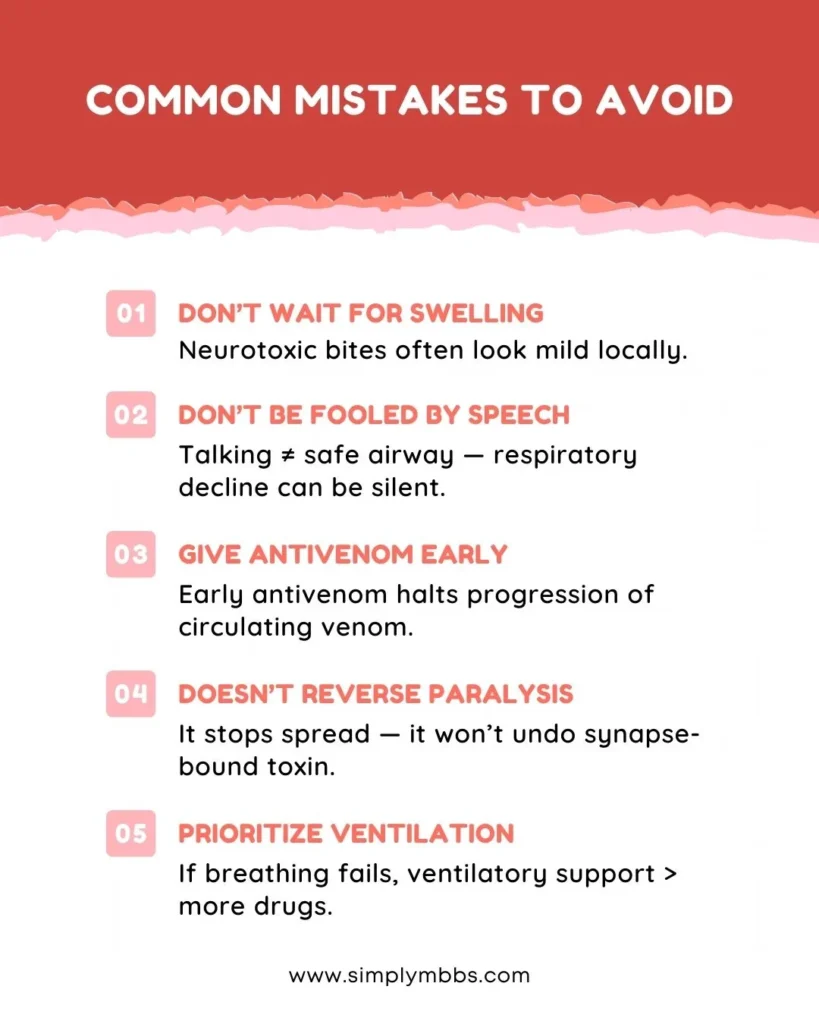

Common Mistakes to Avoid

-

Misdiagnosis as Central Neurological Disorders:

-

Stroke or myasthenia gravis presentations can mimic early neurotoxic signs.

-

-

Improper First Aid:

-

Tourniquets and incisions increase local tissue injury and risk of compartment syndrome.

-

-

Delayed Antivenom Administration:

-

Fear of serum reactions should not overshadow the life-saving benefit of antivenom.

-

-

Neglecting Ventilatory Support:

-

Waiting for severe hypoxia before intubation increases mortality risk.

-

-

Inadequate Monitoring Post-Antivenom:

-

Serial WBCT and clinical reassessment necessary to guide repeat dosing.

-

FAQs on Neuroparalytic Snake Bite

-

What are the earliest clinical signs of a neurotoxic snakebite?

Ptosis and diplopia due to involvement of extraocular muscles and high neuromuscular junction density. -

Should a tourniquet be applied at the bite site?

No—tourniquets can cause ischemic injury and concentrate venom locally, worsening tissue damage. -

How are antivenom reactions prevented and managed?

Premedicate with antihistamines and steroids; administer antivenom slowly; have epinephrine ready for anaphylaxis. -

When is mechanical ventilation indicated?

Signs of respiratory fatigue—SpO₂ <90% on oxygen, rising PaCO₂, severe bulbar muscle weakness. -

Are oral medications effective against neurotoxic envenomation?

No—IV antivenom and ventilatory support remain the cornerstone of treatment.

Exam-Style Question & Answer Section

Question (20 Marks):

“A 24-year-old male presents to the emergency department two hours after a snakebite. He has bilateral ptosis, dysarthria, and generalized weakness. Outline the pathophysiology, clinical staging, laboratory evaluation, and management plan for neuroparalytic snakebite. Include indications for first aid, antivenom administration, and supportive care.”

Model Answer:

-

Pathophysiology: Presynaptic toxins deplete acetylcholine vesicles; postsynaptic toxins block nicotinic receptors at the motor endplate.

-

Clinical Staging:

- Stage I: Ocular involvement—ptosis, diplopia.

- Stage II: Bulbar involvement—dysphagia, dysarthria.

- Stage III: Generalized muscle weakness.

- Stage IV: Respiratory failure—hypoxia, hypercapnia.

-

Laboratory Evaluation:

- 20-minute WBCT: assess for hemotoxic components.

- PT, aPTT: typically normal in pure neurotoxicity.

- CBC, serum electrolytes, renal function tests.

-

Management Plan:

- First Aid: Calm reassurance, limb immobilization, no tourniquets/incisions, rapid transport.

- Antivenom: Polyvalent antivenom 100 mL IV over 1 hour (India) or monovalent equine antivenom 3–5 mL IV bolus (USA).

- Premedication: Antihistamines, steroids if high reaction risk.

- Supportive Care: Early intubation if SpO₂ <90% or rising PaCO₂; mechanical ventilation; fluid management; physiotherapy; nutrition.

Diagram Prompt:

“Draw a schematic of the neuromuscular junction demonstrating presynaptic and postsynaptic neurotoxin actions.”

Viva Tips:

- Describe differences between presynaptic and postsynaptic toxins.

- Highlight importance of 20-minute WBCT in guiding antivenom dosing.

- Explain ventilatory settings for neuroparalytic patients.

Last-Minute Checklist:

- Early ocular signs recognition.

- First aid do’s and don’ts.

- Antivenom types, dosages, and reaction management.

- Ventilatory indications and supportive care essentials.

Conclusion

Neuroparalytic snakebite represents a medical emergency where early recognition, prompt antivenom therapy, and appropriate supportive care are paramount. MBBS students and clinicians must master the underlying toxin mechanisms, clinical progression, and resource-specific treatment protocols to optimize patient outcomes. Equally, disseminating accurate first-aid information empowers communities to seek timely care, mitigating morbidity and mortality.

Enhance your clinical acumen and exam preparedness by subscribing to Simply MBBS. Access evidence-based guides, interactive case studies, and exam-focused resources designed by experts. Stay updated, stay ahead—join our newsletter today.