Have you ever wondered if your daily calcium supplements could cause serious health problems? A 55-year-old woman was rushed to the emergency room with confusion, severe nausea, and weakness. Her calcium levels were dangerously high at 14.5 mg/dL. The culprit? She had been taking excessive calcium carbonate tablets for months to prevent osteoporosis. This scenario represents milk alkali syndrome, a preventable yet potentially life-threatening condition that every medical student, healthcare provider, and health-conscious individual should understand.

Milk alkali syndrome has emerged as the third most common cause of hypercalcemia in modern medicine, following hyperparathyroidism and malignancy. Despite being first described nearly a century ago, this condition continues to challenge clinicians and affects thousands of patients worldwide who unknowingly consume excessive calcium supplements. Understanding this syndrome is crucial for preventing complications, making accurate diagnoses, and providing optimal patient care.

What is Milk Alkali Syndrome?

Definition from Standard Medical Literature

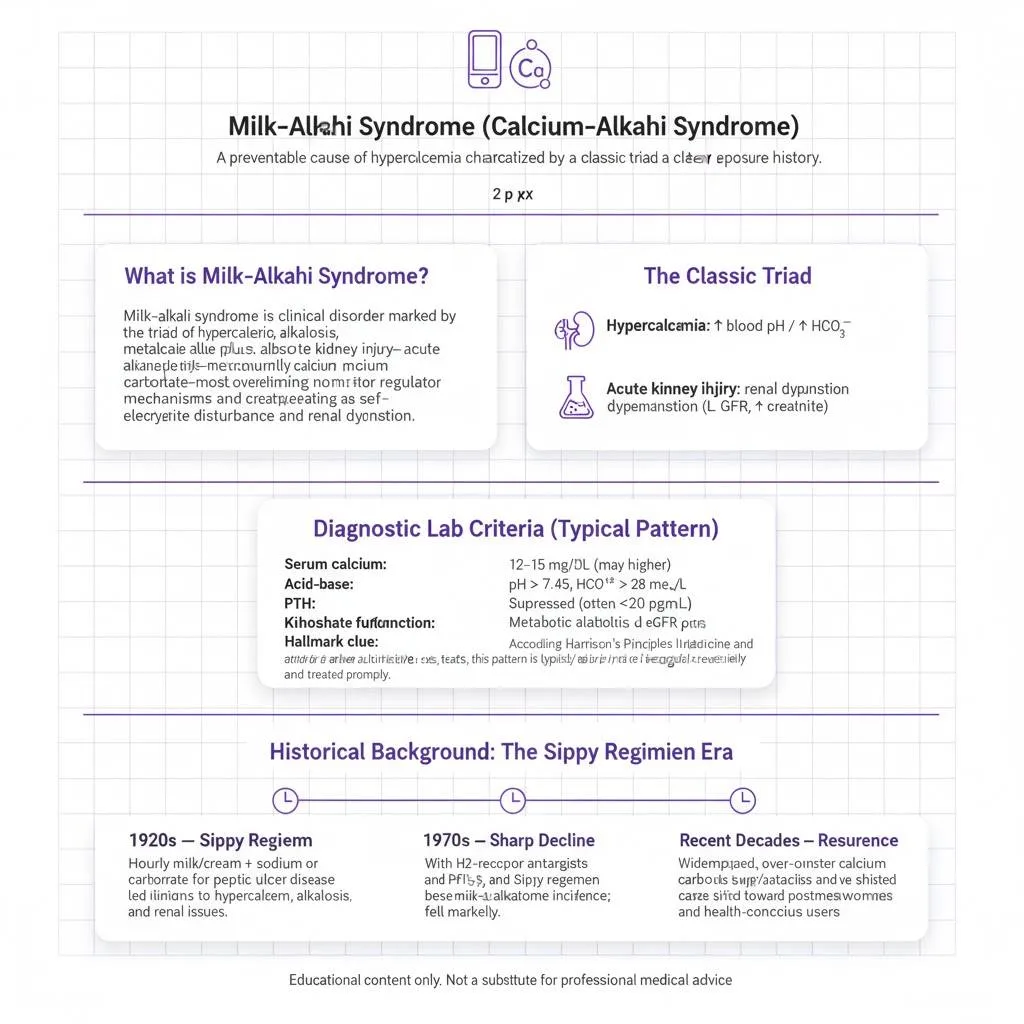

Milk alkali syndrome is a clinical disorder characterized by the classic triad of elevated serum calcium levels (hypercalcemia), metabolic alkalosis (increased blood pH), and acute kidney injury (renal dysfunction). This condition results from the excessive ingestion of calcium combined with absorbable alkali substances, most commonly calcium carbonate. The syndrome develops when calcium intake overwhelms the body’s regulatory mechanisms, creating a self-perpetuating cycle of electrolyte disturbances and kidney dysfunction.

According to Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine and other authoritative medical textbooks, milk-alkali syndrome represents a reversible form of hypercalcemia that can progress to permanent kidney damage if not recognized and treated promptly. The condition is defined by specific laboratory findings including hypercalcemia typically ranging from 12-15 mg/dL, metabolic alkalosis with elevated blood pH above 7.45 and bicarbonate levels exceeding 28 mEq/L, suppressed parathyroid hormone levels below 20 pg/mL, and acute kidney injury with elevated creatinine and reduced glomerular filtration rate. The hallmark feature distinguishing this syndrome from other causes of hypercalcemia is the presence of metabolic alkalosis alongside hypercalcemia, a combination rarely seen in other conditions.

Historical Background: The Sippy Regimen Era

The fascinating history of milk alkali syndrome dates back to the 1920s when Dr. Bertram Sippy introduced a revolutionary treatment for peptic ulcer disease. The Sippy regimen consisted of hourly administration of milk and cream combined with sodium bicarbonate or calcium carbonate powder. This approach aimed to neutralize gastric acid and promote ulcer healing. However, physicians soon observed that some patients developed a peculiar syndrome with elevated calcium levels, alkalosis, and kidney problems.

During the mid-20th century, milk alkali syndrome was one of the most common causes of hypercalcemia in hospitalized patients, particularly affecting men with peptic ulcer disease. The incidence dramatically declined after the 1970s with the introduction of H2-receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors for peptic ulcer treatment, making the Sippy regimen obsolete. Interestingly, the syndrome has resurged in recent decades due to widespread use of over-the-counter calcium carbonate supplements and calcium-containing antacids. The modern epidemiology shows a shift toward affecting postmenopausal women taking calcium supplements for osteoporosis prevention, making it relevant once again in contemporary medical practice.

Why Understanding Milk Alkali Syndrome Matters

Clinical Significance for Healthcare Professionals

Recognizing milk alkali syndrome is essential for physicians, nurses, and pharmacists because this condition often mimics other serious disorders. Misdiagnosis can lead to unnecessary invasive testing, inappropriate treatments, and preventable complications. The syndrome accounts for approximately 12% of all hypercalcemia cases in ambulatory settings, making it a relatively common clinical challenge. Early identification allows for simple interventions—stopping calcium and alkali intake—that can reverse the condition completely in most cases, contrasting sharply with other causes of hypercalcemia that may require surgery, chemotherapy, or long-term medical management.

For medical students and residents preparing for clinical rotations and board examinations, milk alkali syndrome represents an important differential diagnosis in patients presenting with hypercalcemia. Understanding the pathophysiology helps students grasp fundamental concepts of calcium homeostasis, acid-base balance, and kidney function. Questions about this syndrome frequently appear on USMLE, PLAB, NEET-PG, and other medical licensing examinations worldwide, testing both diagnostic reasoning and management skills. The syndrome provides an excellent teaching case for understanding positive feedback loops in pathophysiology and the importance of detailed medication history-taking.

Importance for General Public and Patients

The growing prevalence of milk alkali syndrome reflects modern healthcare trends emphasizing preventive medicine and self-care. Millions of people worldwide take calcium supplements daily for bone health, particularly postmenopausal women at risk for osteoporosis. Without proper guidance, these well-intentioned individuals may consume excessive amounts, especially when combining multiple calcium-containing products like fortified foods, antacids, and dietary supplements. Over 43% of Americans take calcium supplements regularly, and the widespread availability of over-the-counter calcium products has created a false sense of safety among consumers who view these as harmless “natural” supplements rather than medications capable of causing serious adverse effects.

Understanding risk factors and warning signs empowers patients to use calcium supplements safely. This knowledge is particularly valuable for individuals with pre-existing kidney disease who have impaired calcium excretion, those taking thiazide diuretics which reduce urinary calcium loss, people consuming high-dose vitamin D supplements that enhance intestinal calcium absorption, and individuals combining multiple calcium sources unknowingly. Early symptom recognition can prevent progression to severe complications requiring hospitalization, and simple lifestyle modifications can eliminate risk entirely while still maintaining adequate calcium intake for bone health.

Read More : Venous Thromboembolism (VTE): Risk Factors, Diagnosis (D-dimer/Imaging), and Management

The Classic Triad: Key Features of Milk Alkali Syndrome

Milk alkali syndrome is defined by three core components that occur together, creating a distinctive clinical and laboratory presentation. Understanding each component helps clinicians recognize the syndrome promptly and distinguish it from other causes of hypercalcemia.

The Three Defining Components:

1. Hypercalcemia (Elevated Calcium Levels)

Hypercalcemia, defined as serum calcium levels above 10.5 mg/dL (2.6 mmol/L), represents the hallmark feature of milk alkali syndrome. Patients typically present with calcium levels ranging from 12 to 15 mg/dL, though levels can occasionally exceed 16 mg/dL in severe cases. The elevated calcium results from excessive intestinal absorption that overwhelms normal regulatory mechanisms, particularly when vitamin D levels are adequate or elevated. The severity of hypercalcemic symptoms correlates with both the absolute calcium level and the rapidity of elevation.

Mild hypercalcemia (10.5-12 mg/dL) may cause subtle symptoms like fatigue, constipation, and difficulty concentrating that patients often attribute to other causes. Moderate hypercalcemia (12-14 mg/dL) produces more pronounced manifestations including nausea, vomiting, profound weakness, polyuria, and polydipsia. Severe hypercalcemia above 14 mg/dL can cause confusion, altered mental status, cardiac arrhythmias, and potentially life-threatening complications. A classic mnemonic helps students remember hypercalcemia symptoms: “stones, bones, groans, and psychiatric overtones,” referring to kidney stones, bone pain, abdominal discomfort, and mental status changes.

2. Metabolic Alkalosis (Elevated Blood pH)

Metabolic alkalosis in milk alkali syndrome develops through multiple interconnected mechanisms. The condition manifests as elevated blood pH (above 7.45) and increased serum bicarbonate levels (typically above 28 mEq/L). When patients ingest large amounts of calcium carbonate or other absorbable alkali, they directly add bicarbonate to the bloodstream. Additionally, hypercalcemia impairs kidney function, reducing the kidneys’ ability to excrete excess bicarbonate effectively. The resulting volume depletion from hypercalcemia-induced polyuria triggers compensatory proximal tubular bicarbonate reabsorption, further worsening the alkalosis.

The alkalotic state creates a dangerous positive feedback loop that perpetuates and worsens the syndrome. Alkalosis increases calcium reabsorption in the distal tubules of the nephron, further worsening hypercalcemia. This metabolic derangement also shifts the equilibrium between ionized and protein-bound calcium, potentially masking the true severity of calcium elevation when measuring only total serum calcium. The presence of metabolic alkalosis alongside hypercalcemia is the key distinguishing feature that immediately suggests milk-alkali syndrome rather than other causes of hypercalcemia like primary hyperparathyroidism or malignancy, which typically present with normal acid-base status.

3. Acute Kidney Injury (Renal Dysfunction)

Acute kidney injury (AKI) completes the classic triad of milk alkali syndrome, typically presenting with elevated serum creatinine and reduced glomerular filtration rate. The kidney dysfunction develops through several pathologic mechanisms working simultaneously. Hypercalcemia causes direct vasoconstriction of renal blood vessels, decreasing blood flow to the kidneys and reducing glomerular filtration. High calcium levels impair the kidneys’ concentrating ability by interfering with antidiuretic hormone action in the collecting ducts, leading to a nephrogenic diabetes insipidus-like state with massive water losses.

Calcium can precipitate in renal tubules, causing nephrocalcinosis and direct tubular damage. The combination of reduced renal perfusion, tubular injury, and impaired sodium-potassium-chloride transport in the thick ascending limb of Henle creates progressive kidney dysfunction. Laboratory markers typically show elevated serum creatinine (often 2-4 mg/dL), elevated blood urea nitrogen, and a BUN/creatinine ratio often exceeding 20:1 reflecting prerenal azotemia from volume depletion. Early recognition and treatment can reverse kidney injury in most cases, but delayed diagnosis may result in chronic kidney disease requiring long-term management or dialysis. The reversibility of renal function depends heavily on the duration and severity of hypercalcemia before treatment initiation.

How Milk Alkali Syndrome Develops: Pathophysiology Explained

The Vicious Cycle of Calcium and Alkalosis

The pathophysiology of milk alkali syndrome exemplifies a dangerous positive feedback loop in medicine, where initial disturbances trigger compensatory responses that paradoxically worsen rather than correct the problem. Understanding this mechanism is crucial for medical students and explains why the syndrome rapidly progresses without intervention.

The syndrome begins when individuals consume excessive calcium—typically 4-5 grams daily, far exceeding the recommended 1000-1200 mg. This calcium, usually combined with absorbable alkali as calcium carbonate, is rapidly absorbed by the small intestine within 3-4 hours, causing acute serum calcium elevation. Hypercalcemia triggers compensatory responses that ultimately create a self-perpetuating cycle through activated calcium-sensing receptors throughout the body, particularly in the kidneys.

Activated renal calcium-sensing receptors cause afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction in the glomeruli, reducing glomerular filtration rate and renal blood flow. Simultaneously, hypercalcemia inhibits the sodium-potassium-2-chloride (NKCC2) cotransporter in the thick ascending limb of Henle, impairing urinary concentration. This produces a nephrogenic diabetes insipidus-like state with polyuria—patients produce 3-4 liters of dilute urine daily, causing progressive volume depletion.

As dehydration develops, kidneys attempt volume conservation by increasing proximal tubular bicarbonate reabsorption. This compensatory mechanism exacerbates metabolic alkalosis, already present from direct alkali ingestion. The alkalotic environment then increases passive calcium reabsorption in distal convoluted tubules, creating more hypercalcemia and perpetuating the cycle.

Worsening kidney dysfunction prevents adequate calcium excretion while continued excessive intake maintains elevated levels. This creates the vicious cycle: hypercalcemia → renal dysfunction → volume depletion → bicarbonate reabsorption → alkalosis → increased calcium reabsorption → worsening hypercalcemia. Without intervention—stopping calcium intake and providing aggressive intravenous hydration—the syndrome worsens, potentially causing irreversible kidney damage, cardiac arrhythmias, altered consciousness, and death in extreme cases.

Role of Parathyroid Hormone Suppression

A critical component in understanding the mechanism of milk alkali syndrome involves parathyroid hormone (PTH) regulation. Normally, PTH maintains calcium homeostasis by responding to serum calcium levels through a sophisticated negative feedback system. The parathyroid glands contain calcium-sensing receptors that constantly monitor blood calcium levels. When calcium rises, these receptors detect the change and suppress PTH secretion. In milk alkali syndrome, hypercalcemia causes profound PTH suppression, with levels typically falling below 20 pg/mL and often below 10 pg/mL in severe cases, compared to the normal range of 10-65 pg/mL.

While PTH suppression initially represents an appropriate physiologic response to hypercalcemia, it paradoxically contributes to syndrome progression in several ways. Low PTH levels reduce calcitriol (active vitamin D) production in the kidneys by decreasing 1-alpha-hydroxylase activity, which should theoretically decrease intestinal calcium absorption. However, in the presence of continued excessive calcium intake, this protective mechanism proves insufficient. Additionally, some patients have inadequate suppression of calcitriol despite hypercalcemia, leading to continued hyperabsorption of dietary calcium.

The suppressed PTH also significantly affects phosphate handling in the kidneys. PTH normally promotes phosphate excretion by inhibiting phosphate reabsorption in the proximal tubules. When PTH is suppressed, the kidneys retain phosphate, causing serum phosphate levels to remain normal or elevated. This laboratory finding is diagnostically crucial because it helps clinicians distinguish milk-alkali syndrome from primary hyperparathyroidism, where elevated PTH causes phosphate wasting and hypophosphatemia. The combination of suppressed PTH with normal or elevated phosphate levels, along with metabolic alkalosis, creates a distinctive laboratory pattern that points definitively toward the diagnosis of milk alkali syndrome rather than other causes of hypercalcemia.

Read More : Acute Kidney Injury (AKI): Clinical Classification, Urine Indices, and Management

Milk Alkali Syndrome Symptoms: What to Watch For

Acute Presentation

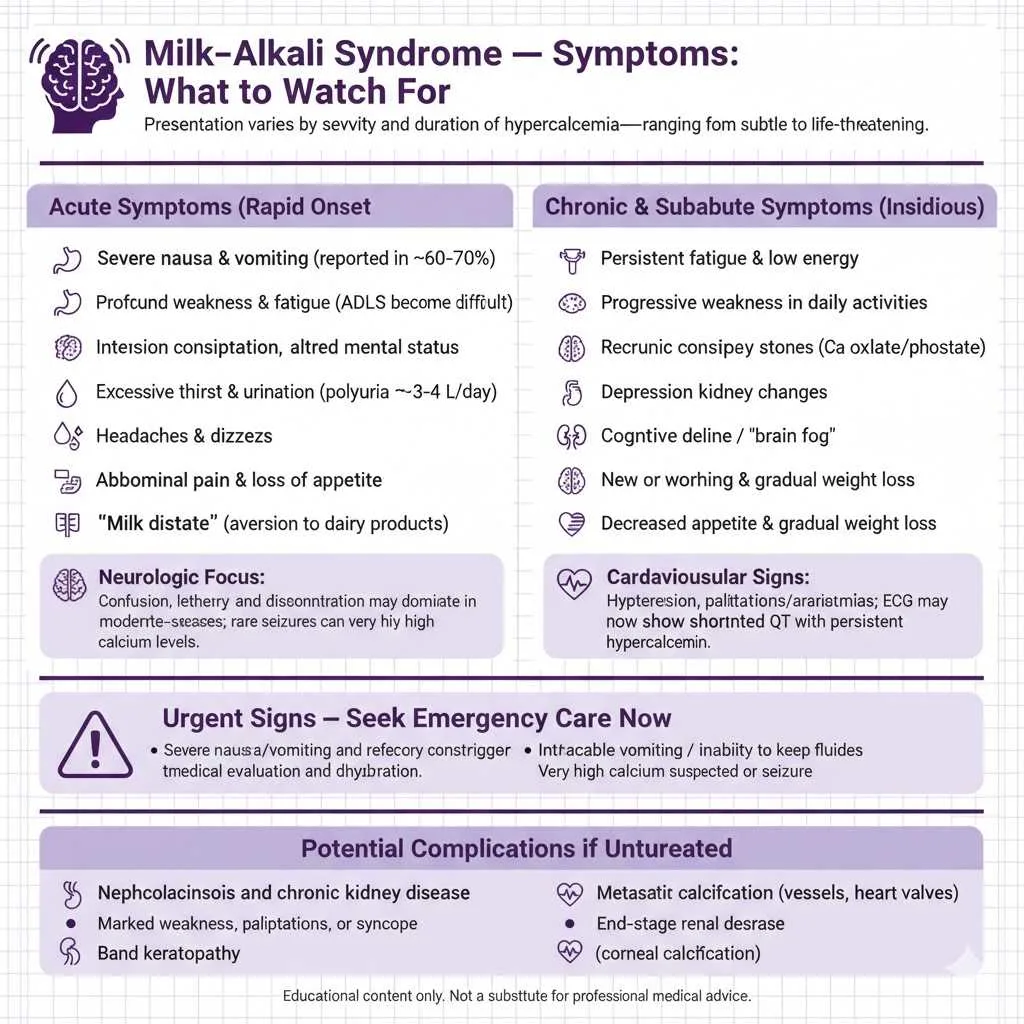

The symptoms of milk alkali syndrome vary significantly depending on the severity and duration of calcium elevation, ranging from subtle findings easily overlooked to dramatic life-threatening manifestations. Acute cases develop rapidly over days to weeks and present with more dramatic clinical features.

Common Acute Symptoms:

- Severe nausea and vomiting (present in 60-70% of patients)

- Profound weakness and fatigue making daily activities difficult

- Intense constipation due to decreased gastrointestinal motility

- Confusion, disorientation, or altered mental status

- Excessive thirst (polydipsia) and urination (polyuria, 3-4 liters daily)

- Headaches and dizziness

- Abdominal pain and loss of appetite

- “Milk distaste”—aversion to dairy products (protective mechanism)

Neurological symptoms often dominate the clinical picture in moderate to severe cases. Patients may exhibit confusion, disorientation, lethargy, or altered mental status ranging from mild cognitive impairment to profound stupor requiring intensive care. Some individuals develop headaches, dizziness, or vertigo that interfere with normal functioning. In severe cases with calcium levels exceeding 16 mg/dL, seizures can occur, though this remains relatively uncommon. The intense thirst and excessive urination paradoxically worsen the condition by causing volume depletion, which perpetuates the metabolic abnormalities.

Gastrointestinal manifestations are often the initial presenting complaints that prompt medical evaluation. Patients commonly experience severe nausea and vomiting, which ironically may limit further calcium intake and prevent even more severe hypercalcemia, acting as a natural protective mechanism. Many patients develop profound constipation that doesn’t respond to typical over-the-counter laxatives, caused by hypercalcemia’s inhibitory effects on smooth muscle contractility in the intestines. The combination of nausea, vomiting, and constipation often leads to decreased oral intake and further volume depletion, exacerbating the metabolic derangements.

Chronic and Subacute Manifestations

Chronic milk alkali syndrome develops gradually over months when patients consistently consume moderately excessive calcium amounts without reaching acutely dangerous levels. These individuals may present with subtler, insidious symptoms that complicate timely diagnosis and often lead to delayed recognition until complications develop.

Chronic Symptom Patterns:

- Persistent fatigue and low energy (often attributed to aging or stress)

- Progressive weakness affecting ability to perform daily activities

- Chronic constipation resistant to dietary modifications

- Recurrent kidney stones (calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate)

- Depression and mood changes

- Cognitive decline and “brain fog”

- New-onset or worsening hypertension

- Decreased appetite and gradual weight loss

Cardiovascular manifestations develop insidiously in chronic cases. Patients often experience new-onset hypertension or worsening of pre-existing high blood pressure due to calcium’s vasoconstrictive effects and volume expansion from increased sodium reabsorption. Some patients complain of palpitations or irregular heartbeats reflecting subclinical cardiac arrhythmias. Electrocardiogram changes may show shortened QT intervals, a classic finding in hypercalcemia that increases risk of dangerous ventricular arrhythmias. The cardiovascular risks increase substantially with calcium levels persistently above 12 mg/dL.

Long-term complications of untreated chronic milk alkali syndrome include nephrocalcinosis where calcium deposits accumulate in kidney tissue causing permanent structural damage, metastatic calcification with calcium deposits in soft tissues including blood vessels and heart valves, chronic kidney disease potentially progressing to end-stage renal disease requiring dialysis, and corneal calcification (band keratopathy) visible on eye examination in severe chronic cases. The insidious nature of chronic presentations means patients may not seek medical attention until acute-on-chronic decompensation occurs, often triggered by dehydration from illness, heat exposure, or diuretic use, suddenly converting a stable chronic situation into a medical emergency.

Which Type of Antacids Can Lead to Milk Alkali Syndrome?

Calcium Carbonate: The Primary Culprit

Calcium carbonate-containing antacids represent the most common cause of modern milk-alkali syndrome cases. These products, marketed under brand names like Tums, Rolaids, and countless generic formulations, are ubiquitous in pharmacies and supermarkets. Each tablet typically contains 500-750 mg of elemental calcium, and manufacturers often recommend multiple doses throughout the day for heartburn relief. A patient taking the maximum recommended dose of some antacids could consume 4-7 grams of elemental calcium daily, far exceeding safe limits and creating substantial risk for developing the syndrome.

Calcium carbonate serves dual purposes that drive its popularity but also increase its danger. It neutralizes gastric acid providing rapid heartburn relief, and it simultaneously provides supplemental calcium marketed for bone health. This dual benefit particularly attracts postmenopausal women concerned about osteoporosis who may view these products as serving two beneficial purposes with one convenient tablet. However, this same property makes calcium carbonate uniquely dangerous for causing milk alkali syndrome. When patients take these antacids for acid reflux, they often consume them frequently throughout the day and evening, sometimes exceeding recommended doses to achieve adequate symptom relief. The carbonate component directly contributes bicarbonate that causes alkalosis, while the high calcium load causes hypercalcemia, perfectly setting up both components necessary for the syndrome.

Common High-Risk Calcium Carbonate Products:

- Tums (regular, extra strength, ultra strength)

- Rolaids (original and various formulations)

- Alka-Mints

- Caltrate (marketed as calcium supplement)

- Os-Cal (calcium supplement)

- Generic calcium carbonate (countless store brands)

- Viactiv calcium chews

The risk increases dramatically when patients combine calcium carbonate antacids with separate calcium supplements, calcium-fortified foods like orange juice and cereals, and dairy products rich in calcium. Many patients remain completely unaware that they’re consuming excessive total calcium from multiple sources because they don’t think to add up calcium from different product categories. Additionally, certain medications compound the problem: thiazide diuretics reduce urinary calcium excretion, vitamin D supplements enhance intestinal calcium absorption, and impaired kidney function limits calcium elimination—all substantially elevating risk when combined with calcium carbonate products.

Safer Alternatives and Other Alkali Sources

While calcium carbonate dominates as the causative agent, understanding other alkali sources and identifying safer alternatives is crucial for prevention of milk alkali syndrome.

Safer Antacid Alternatives (Lower MAS Risk):

- Aluminum hydroxide antacids (Amphojel)—no calcium content

- Magnesium hydroxide or Milk of Magnesia—causes diarrhea at high doses, self-limiting

- Aluminum-magnesium combinations (Maalox, Mylanta)—balanced formulation

- Proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole, esomeprazole)—superior for chronic reflux

- H2-receptor antagonists (famotidine)—effective without calcium

Regarding magnesium-containing antacids, these generally pose less risk for milk alkali syndrome because magnesium typically causes diarrhea at high doses, which limits absorption and discourages excessive intake through unpleasant side effects. However, in patients with kidney disease who have impaired magnesium excretion, these products can still contribute to electrolyte imbalances and cause hypermagnesemia. Aluminum-containing antacids do not cause milk-alkali syndrome but carry other risks like aluminum toxicity with chronic use, particularly in patients with renal insufficiency, and can cause constipation and phosphate depletion with prolonged administration.

Other absorbable alkali that can contribute to syndrome development include sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) sometimes used as a home remedy for indigestion, which contains significant alkali that can trigger the syndrome when consumed excessively alongside calcium-rich foods or supplements. Some proprietary antacid formulations combine multiple alkali compounds, amplifying the risk. Calcium citrate supplements, while generally safer than calcium carbonate because they don’t contribute to alkalosis and are better absorbed, can still contribute to hypercalcemia if consumed excessively, though they require higher doses to cause problems.

Milk Alkali Syndrome Lab Results: Diagnostic Criteria

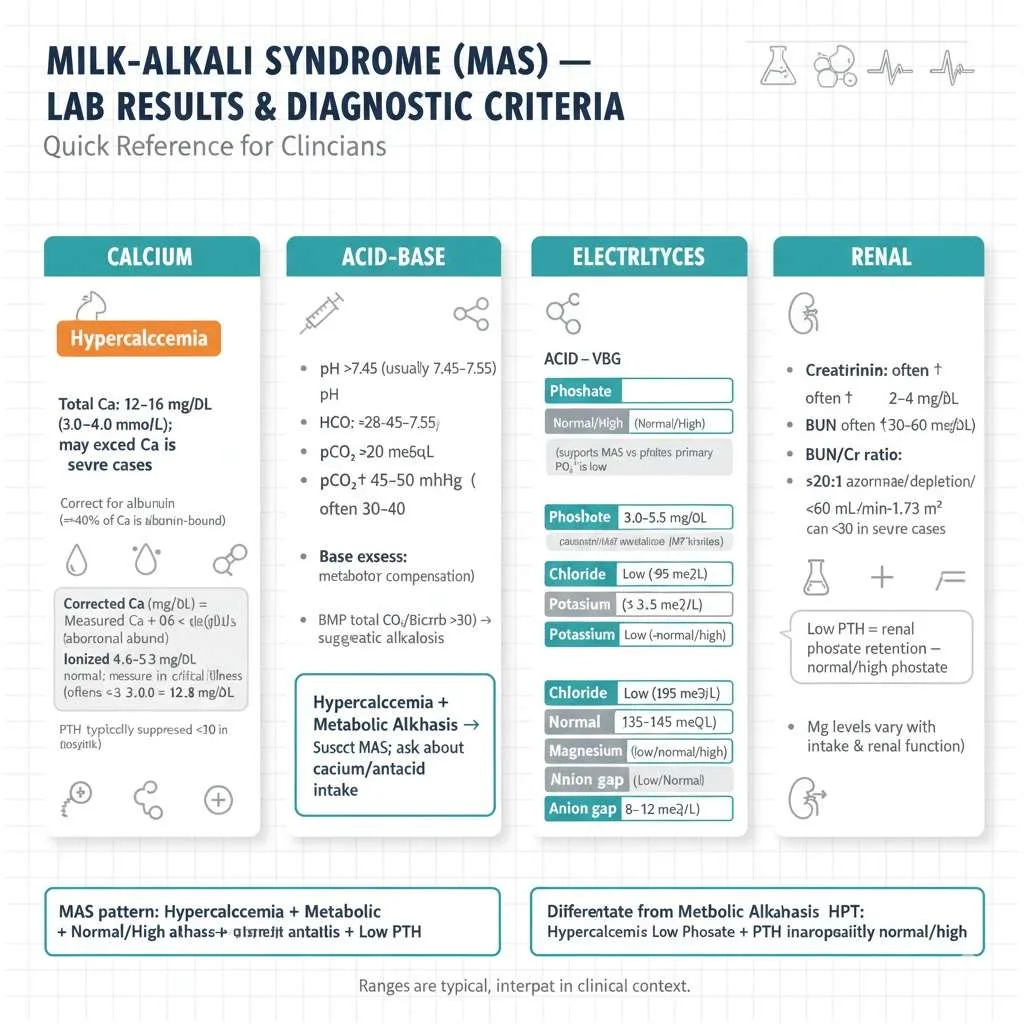

Calcium Levels

The laboratory diagnosis of milk alkali syndrome begins with documenting hypercalcemia through comprehensive calcium measurement. Total serum calcium levels typically range from 12-16 mg/dL (3.0-4.0 mmol/L) in affected patients, though values can occasionally exceed this range in severe cases. It is crucial to measure or correct calcium for albumin levels because approximately 40% of serum calcium binds to albumin. The corrected calcium formula adds 0.8 mg/dL to the measured calcium for every 1 g/dL that albumin falls below 4.0 g/dL. For example, if measured calcium is 12 mg/dL and albumin is 3.0 g/dL, the corrected calcium equals 12 + 0.8 × (4.0 – 3.0) = 12.8 mg/dL, revealing a more severe hypercalcemia than the uncorrected value suggested.

Alternatively, measuring ionized calcium (the physiologically active form) provides a more accurate assessment, with normal values ranging from 4.6-5.3 mg/dL. Ionized calcium measurement is particularly valuable in critically ill patients, those with abnormal albumin levels, and when there is discrepancy between clinical presentation and total calcium levels. The calcium elevation in milk alkali syndrome can be dramatic and develop rapidly, with serial measurements often showing progressive increase if calcium ingestion continues. When evaluating hypercalcemia, clinicians should simultaneously measure parathyroid hormone (PTH), which is characteristically suppressed (typically <20 pg/mL, often <10 pg/mL in severe cases) in milk alkali syndrome, helping distinguish it from primary hyperparathyroidism where PTH is elevated or inappropriately normal despite hypercalcemia.

Arterial Blood Gas and Acid-Base Findings

Arterial blood gas analysis or venous chemistry panels reveal metabolic alkalosis as a defining feature of milk alkali syndrome labs, providing crucial diagnostic information. The pH is elevated above 7.45, often ranging from 7.45-7.55 in typical cases, with some severe cases exceeding 7.55. Serum bicarbonate (HCO3-) is increased above 28 mEq/L, frequently reaching 30-40 mEq/L depending on severity and duration. The partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) may be mildly elevated at 45-50 mmHg as respiratory compensation for metabolic alkalosis, though compensation is usually incomplete because the respiratory system can only partially compensate for metabolic acid-base disturbances.

The base excess is positive, typically +5 to +15 mEq/L, reflecting the excess alkali in the system. Venous chemistry panels provide similar information more conveniently than arterial sampling for most clinical situations. An elevated total CO2 or bicarbonate level above 30 mEq/L on a basic metabolic panel suggests metabolic alkalosis and should prompt further investigation. The combination of hypercalcemia with metabolic alkalosis immediately raises suspicion for milk-alkali syndrome and should prompt specific questioning about calcium and antacid use. This laboratory pattern distinguishes milk alkali syndrome from other hypercalcemic conditions like hyperparathyroidism or malignancy, where acid-base status is typically normal or may even be acidotic in advanced malignancy with lactic acidosis.

Phosphate and Other Electrolytes

Serum phosphate levels in milk alkali syndrome typically remain normal or elevated, ranging from 3.0-5.5 mg/dL, holding significant diagnostic value. This finding is clinically important because primary hyperparathyroidism, the most common cause of hypercalcemia, typically produces hypophosphatemia (low phosphate below 2.5 mg/dL) due to PTH-mediated renal phosphate wasting. The normal to high phosphate in milk alkali syndrome results from suppressed PTH, which normally promotes renal phosphate excretion. When PTH is low, the kidneys retain phosphate, maintaining or elevating serum levels, creating a distinctive pattern that helps narrow the differential diagnosis.

Complete Electrolyte Patterns in MAS:

- Chloride: Typically low (hypochloremia <95 mEq/L) from urinary losses

- Potassium: May be low (hypokalemia <3.5 mEq/L) from renal losses and alkalosis

- Sodium: Usually normal (135-145 mEq/L) unless significant dehydration

- Magnesium: Variable (may be low, normal, or high depending on intake and kidney function)

- Anion gap: Low or normal (8-12 mEq/L), consistent with alkalosis

Kidney function markers are invariably abnormal, with creatinine elevated above baseline (often 2-4 mg/dL), blood urea nitrogen elevated (often 30-60 mg/dL), and BUN/creatinine ratio frequently exceeding 20:1 reflecting prerenal azotemia from volume depletion. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is reduced below 60 mL/min/1.73m² in most cases, sometimes falling below 30 mL/min/1.73m² in severe presentations. Serum magnesium levels vary depending on multiple factors including dietary intake, use of magnesium-containing products, and degree of kidney dysfunction. Some patients develop hypomagnesemia from increased urinary losses, while others taking combination calcium-magnesium antacids may have normal or elevated levels, particularly if kidney function is significantly impaired.

Read More : Management of Shock: Types, Clinical Assessment, and Latest Guidelines in Resuscitation

Milk Alkali Syndrome vs Other Causes of Hypercalcemia

Comprehensive Comparison Table

Understanding how milk alkali syndrome differs from other hypercalcemic conditions is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate management, preventing unnecessary testing and treatments.

| Feature | Milk Alkali Syndrome | Primary Hyperparathyroidism | Malignancy-Related | Vitamin D Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium Level | 12-15 mg/dL | 10.5-12 mg/dL (mild) | >14 mg/dL (severe) | 12-16 mg/dL |

| PTH | Suppressed (<20) | Elevated or inappropriately normal | Suppressed | Suppressed |

| Phosphate | Normal to high | Low | Variable | High |

| Alkalosis | Present | Absent | Absent | Absent |

| Chloride | Low | High | Normal | Normal |

| 25-OH Vit D | Normal to high | Normal | Normal to low | >150 ng/mL |

| PTHrP | Normal | Normal | Elevated (in humoral type) | Normal |

| Kidney Function | AKI common | Usually normal | Variable | Can have AKI |

| Onset | Acute/subacute | Gradual, chronic | Rapid | Subacute |

| History | Calcium/antacid use | Often asymptomatic | Known cancer | High-dose supplements |

| Reversibility | Rapidly reversible | Requires surgery | Depends on cancer | Slow resolution |

Key Distinguishing Features

Differentiating Milk Alkali Syndrome from Other Hypercalcemic Conditions

Distinguishing milk alkali syndrome from primary hyperparathyroidism is clinically essential because treatments and prognoses differ dramatically. Primary hyperparathyroidism, caused by parathyroid adenoma (80-85%) or hyperplasia (15%), produces mild-moderate hypercalcemia with elevated or inappropriately normal PTH levels. Key laboratory distinctions include low serum phosphate from PTH-mediated renal wasting (versus normal-high phosphate in milk alkali syndrome), high urinary calcium or hypercalciuria (versus low chloride in MAS), and elevated chloride levels (hyperchloremic versus hypochloremic in MAS). Hyperparathyroidism develops chronically, often discovered incidentally on routine labs, with asymptomatic or mild symptoms. Treatment requires parathyroidectomy—surgical removal of the abnormal gland—whereas milk alkali syndrome resolves with conservative management alone.

Malignancy-Related Hypercalcemia

Malignancy-related hypercalcemia presents with severe, rapidly progressive calcium elevation. Patients typically appear systemically ill with evident cancer, though hypercalcemia occasionally precedes cancer diagnosis. Two main mechanisms exist: humoral hypercalcemia where tumors secrete PTH-related peptide (PTHrP) in lung, breast, and kidney cancers; and local osteolytic activity from bone metastases in multiple myeloma and breast cancer. Distinguishing features include severe hypercalcemia often exceeding 14 mg/dL, elevated PTHrP in humoral type, absence of metabolic alkalosis, and poor prognosis linked to underlying malignancy. Treatment involves bisphosphonates, denosumab, and addressing the cancer itself.

Vitamin D Intoxication

Vitamin D intoxication from excessive supplementation (typically >10,000 IU daily for months) causes hypercalcemia with dramatically elevated 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels exceeding 150 ng/mL, often surpassing 200 ng/mL. Like milk alkali syndrome, it features suppressed PTH and high serum phosphate. However, the critical difference is absence of metabolic alkalosis and characteristic vitamin D elevation. Resolution is slow because vitamin D’s fat-soluble nature creates a long half-life (measured in weeks), contrasting with milk alkali syndrome’s rapid reversal after stopping calcium intake.

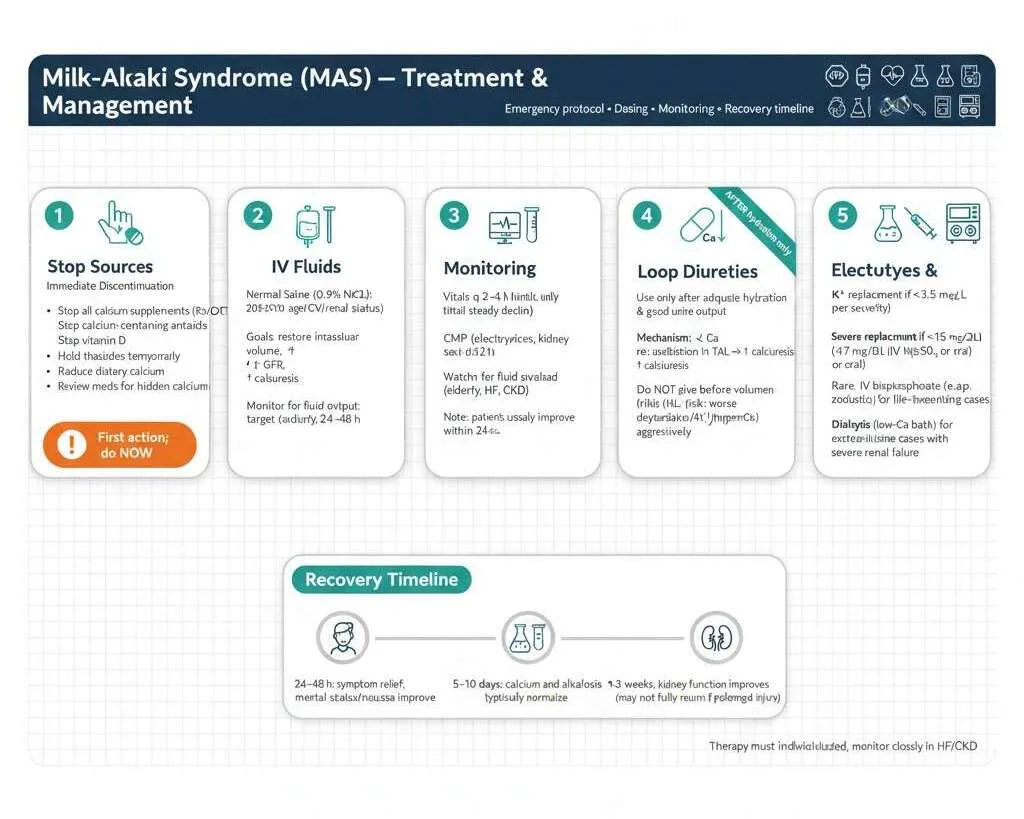

Treatment and Management of Milk Alkali Syndrome

Immediate Interventions

The cornerstone of milk alkali syndrome treatment involves immediately discontinuing the source and providing supportive care to reverse the metabolic derangements. The approach is straightforward but requires attention to detail and careful monitoring.

Emergency Management Protocol:

1. Stop All Calcium and Alkali Sources Immediately

- Discontinue all calcium supplements (prescription and over-the-counter)

- Stop all calcium-containing antacids (Tums, Rolaids, all brands)

- Eliminate vitamin D supplements

- Hold thiazide diuretics temporarily if patient is taking them

- Temporarily reduce dietary calcium intake

- Review entire medication list for hidden calcium sources

2. Aggressive Intravenous Fluid Resuscitation

The most important therapeutic intervention is aggressive intravenous fluid administration. Normal saline (0.9% NaCl) is the fluid of choice, administered initially at 200-300 mL/hour depending on the patient’s cardiovascular status, age, and presence of heart failure or severe kidney disease. Rehydration serves multiple critical purposes: it restores intravascular volume depleted by polyuria, improves kidney perfusion and glomerular filtration rate, and promotes urinary calcium excretion through increased glomerular filtration and decreased proximal tubular calcium reabsorption. Most patients are significantly volume depleted and may require 3-6 liters of intravenous fluids over the first 24 hours, with ongoing fluid administration based on urine output and clinical status.

Close monitoring of fluid balance is essential to avoid complications. Healthcare providers should monitor urine output with a goal exceeding 100 mL/hour, track strict intake and output, assess for signs of fluid overload particularly in elderly patients or those with heart failure, and adjust infusion rates based on response and cardiovascular tolerance. Patients typically begin to feel better within 24-48 hours as calcium levels decline, nausea improves, and mental status clears.

3. Close Clinical and Laboratory Monitoring

- Vital signs every 2-4 hours initially

- Serum calcium every 6-12 hours until declining consistently

- Comprehensive metabolic panel every 6-12 hours (electrolytes, kidney function)

- Cardiac monitoring (continuous telemetry if calcium >14 mg/dL)

- Strict fluid intake and output documentation

4. Loop Diuretics (Only After Adequate Hydration)

Once adequate hydration is achieved and urine output is well-established, loop diuretics like furosemide can be considered to enhance urinary calcium excretion. Furosemide 20-40 mg intravenously every 6-12 hours inhibits calcium reabsorption in the thick ascending limb of Henle, promoting calcium loss in urine. However, diuretics should never be given before volume repletion because this would worsen dehydration, prerenal azotemia, and potentially hypercalcemia. Close monitoring for electrolyte depletion is mandatory with diuretic use, as furosemide causes potassium, magnesium, and sodium losses requiring aggressive repletion.

5. Electrolyte Repletion and Additional Therapies

- Replace potassium if <3.5 mEq/L (oral or IV depending on severity)

- Replace magnesium if <1.7 mg/dL (magnesium sulfate IV or oral supplements)

- For severe cases with calcium >15-16 mg/dL: consider calcitonin 4 IU/kg every 12 hours for rapid but temporary reduction

- Rarely needed: bisphosphonates (zoledronic acid) for life-threatening cases

- Dialysis with low-calcium dialysate reserved for extreme cases with severe kidney failure

Most patients experience significant symptom improvement within 24-48 hours, calcium normalization within 5-10 days, metabolic alkalosis resolution within 5-10 days, and kidney function improvement over 1-3 weeks, though complete recovery to baseline may not occur if prolonged damage occurred.

Long-Term Management and Follow-Up

After the acute crisis resolves, patients require careful follow-up to prevent recurrence and address underlying conditions that prompted calcium supplementation in the first place.

Follow-Up Schedule and Monitoring:

- Week 1-2 post-discharge: Outpatient visit within 7-10 days, check calcium and kidney function

- Weeks 3-4: Repeat labs to ensure sustained normal calcium levels

- Months 2-3: Monthly monitoring to detect any recurrence

- Month 6: Final reassessment, bone density testing if indicated

Patient education is paramount in preventing recurrence. Adults should consume 1000-1200 mg calcium daily, often achievable through dietary sources without supplements. When supplementation is necessary, take maximum 500-600 mg per dose (optimal absorption limit) with 4-6 hours between doses. Calcium citrate is safer than calcium carbonate for patients with milk-alkali syndrome history because it contains less elemental calcium and doesn’t cause alkalosis.

Healthcare providers must evaluate why patients consumed excessive calcium and offer alternative strategies. Postmenopausal women concerned about osteoporosis should undergo bone density screening and fracture risk counselling, with consideration of alternative treatments including bisphosphonates, denosumab, or selective estrogen receptor modulators instead of calcium supplementation.

Patients using calcium carbonate for acid reflux should transition to proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists, or calcium-free antacids permanently. This comprehensive approach addresses underlying conditions while preventing milk-alkali syndrome recurrence, ensuring both bone health and safety.

Prevention Strategies: Avoiding Milk Alkali Syndrome

Safe Calcium Supplementation Guidelines

Preventing milk alkali syndrome requires adherence to evidence-based calcium supplementation principles and awareness of total calcium intake from all sources combined.

Recommended Daily Calcium Intake by Age/Group:

- Adults 19-50 years: 1000 mg/day (upper limit 2500 mg/day)

- Women >50 years: 1200 mg/day (upper limit 2000 mg/day)

- Men 51-70 years: 1000 mg/day (upper limit 2000 mg/day)

- Men >70 years: 1200 mg/day (upper limit 2000 mg/day)

Patients should first assess their dietary calcium intake before starting supplements. Many individuals can meet requirements through diet alone, eliminating the need for supplements and the risk of milk-alkali syndrome. Dairy products provide substantial calcium with one cup of milk containing approximately 300 mg, yogurt providing 300-400 mg per cup, and cheese contributing 300 mg per 1.5 ounces. Calcium-fortified orange juice provides 350 mg per cup, while fortified plant-based milk alternatives, canned sardines with bones, calcium-set tofu, and dark leafy greens also contribute significant amounts. The strategy should involve tracking typical daily dietary calcium for 3 days, calculating average daily intake from food, and only supplementing the difference to reach the 1000-1200 mg goal while accounting for calcium in multivitamins.

Safe Supplementation Practices When Necessary:

- Choose calcium citrate over calcium carbonate (better absorbed, no alkalosis risk)

- Take maximum 500-600 mg elemental calcium per dose

- Space doses at least 4-6 hours apart if multiple doses needed

- Take supplements with meals to slow absorption

- Drink plenty of water with supplements

- Maintain adequate vitamin D (800-1000 IU daily, avoid mega-doses >4000 IU)

High-Risk Populations Requiring Monitoring

Certain populations face elevated risk for developing milk alkali syndrome and require closer monitoring, individualized recommendations, and possibly avoiding calcium supplements altogether.

High-Risk Groups:

- Chronic kidney disease patients (stages 3-5 with eGFR <60 mL/min)

- Thiazide diuretic users (reduced urinary calcium excretion)

- High-dose vitamin D supplement consumers (>4000 IU daily)

- Granulomatous disease patients (sarcoidosis, tuberculosis)

- Postmenopausal women on multiple osteoporosis treatments

- Elderly patients >75 years with declining kidney function

- Patients with history of kidney stones

For chronic kidney disease patients, calcium supplements should be avoided unless specifically prescribed by a nephrologist, with preference for non-calcium-based phosphate binders if needed and monitoring serum calcium every 3-6 months. Thiazide diuretic users should limit calcium supplementation to 500-600 mg daily maximum or consider alternative antihypertensive medications, with calcium checks every 6 months. Those taking high-dose vitamin D should reduce to 800-1000 IU daily, check 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels targeting 30-50 ng/mL rather than exceeding 80 ng/mL, and monitor calcium every 3-6 months. Patients with granulomatous diseases should avoid calcium and vitamin D supplements unless specifically indicated because granulomas produce calcitriol independently of normal regulation.

Read More : Complete Blood Count Interpretation: Red Flags, Clinical Correlates & Exam Caselets

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Patient-Related Mistakes

Common Errors Patients Make:

- Believing “more calcium equals stronger bones” and exceeding recommended doses

- Not accounting for total calcium from supplements, antacids, fortified foods, and dairy combined

- Using antacids as candy, consuming 10-15 tablets daily instead of recommended 2-4

- Combining multiple calcium products without tracking total intake

- Ignoring early warning symptoms like fatigue, constipation, and confusion

- Self-treating without medical evaluation or bone density testing

- Not reading supplement labels and confusing total calcium with elemental calcium

The “more is better” mentality leads individuals to consume multiple calcium supplements throughout the day, often exceeding 3000-5000 mg daily, not realizing they’re reaching toxic levels. Many patients believe that calcium cannot cause harm because it’s “natural,” leading to dangerous overconsumption. Another critical error involves combining multiple calcium sources without accounting for total intake—a patient might take a calcium supplement, drink calcium-fortified orange juice, consume multiple servings of dairy products, take calcium carbonate antacids for heartburn, and use calcium-containing multivitamins all on the same day, with each source individually seeming reasonable but cumulative load becoming excessive.

Healthcare Provider Errors

Common Mistakes Clinicians Make:

- Failing to obtain thorough medication history including OTC supplements and antacids

- Prescribing calcium without assessing dietary intake or baseline calcium needs

- Missing the diagnosis by not recognizing the classic triad pattern

- Seeing hypercalcemia and immediately ordering malignancy workup without basic history

- Not monitoring high-risk patients with periodic calcium level checks

- Providing inadequate patient education about safe use and warning signs

- Misinterpreting suppressed PTH as “appropriate” without investigating the cause

Healthcare providers sometimes fail to ask about over-the-counter supplements, antacids, and vitamins during medication reconciliation, assuming patients aren’t taking dangerous amounts. This oversight allows dangerous consumption patterns to continue undetected until the patient presents with symptomatic hypercalcemia. Another common error involves prescribing calcium supplementation without assessing dietary calcium intake or total calcium needs, recommending 1000-1500 mg of supplemental calcium without determining how much the patient already consumes through diet, pushing total intake well above safe limits. Clinicians sometimes miss the diagnosis by failing to recognize the characteristic triad or by ordering extensive workups for malignancy or hyperparathyroidism without first obtaining a careful history of calcium and antacid use, when the presence of metabolic alkalosis on blood gas or chemistry panel should immediately prompt questions about absorbable alkali intake.

Frequently Asked Questions About Milk Alkali Syndrome

Q : What is milk alkali syndrome?

A: Milk alkali syndrome is a medical condition characterized by high calcium levels (hypercalcemia), metabolic alkalosis (elevated blood pH), and acute kidney injury. It occurs when someone consumes excessive amounts of calcium supplements or calcium-containing antacids, typically more than 4-5 grams daily.

Q : What causes milk alkali syndrome?

A: The syndrome is caused by consuming too much calcium carbonate from supplements or antacids like Tums and Rolaids. The carbonate creates alkalosis while excessive calcium overwhelms the body’s ability to regulate calcium levels, especially when combined with vitamin D supplements or dehydration.

Q : How much calcium is too much?

A: Adults should not exceed 2000-2500 mg of calcium daily from all sources combined (food, supplements, antacids). Most cases of milk alkali syndrome occur when people consume 4000-5000 mg or more daily, though susceptible individuals may develop it at lower doses.

Q : What are the main symptoms?

A: Common symptoms include severe nausea and vomiting, confusion or mental fog, profound weakness and fatigue, intense constipation, excessive thirst and urination, and loss of appetite. Symptoms can develop within days to weeks of excessive calcium intake.

Q : Is milk alkali syndrome reversible?

A: Yes, it’s highly reversible when caught early. Most patients recover completely within 5-10 days after stopping calcium intake and receiving IV fluids. However, prolonged cases may cause permanent kidney damage if not treated promptly.

Q : How is it diagnosed?

A: Diagnosis requires blood tests showing elevated calcium (>12 mg/dL), metabolic alkalosis (high pH and bicarbonate), acute kidney injury (elevated creatinine), suppressed PTH (<20 pg/mL), and normal or high phosphate levels—combined with a history of excessive calcium intake.

Q : What’s the treatment?

A: Immediate treatment includes stopping all calcium supplements and antacids, aggressive IV fluid hydration (3-6 liters over 24 hours), and close monitoring of calcium levels every 6-12 hours. Most patients improve significantly within 48 hours.

Q : Which antacids are safest?

A: Avoid calcium carbonate antacids (Tums, Rolaids). Safer alternatives include aluminum-magnesium antacids (Maalox, Mylanta) for occasional use, or better yet, proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole) or H2-blockers (famotidine) for chronic acid reflux.

Conclusion and Key Takeaways

Milk alkali syndrome represents a preventable yet potentially serious condition affecting thousands of individuals worldwide who consume excessive calcium supplements and antacids. The classic triad of hypercalcemia, metabolic alkalosis, and acute kidney injury—combined with suppressed parathyroid hormone and a history of calcium carbonate intake—makes diagnosis straightforward when clinicians maintain appropriate clinical suspicion.

The excellent prognosis of milk-alkali syndrome contrasts sharply with many other causes of hypercalcemia. Most patients experience complete resolution within 5-10 days after discontinuing calcium sources and receiving appropriate supportive care with intravenous fluids. This favorable outcome underscores the critical importance of early recognition and prompt intervention. However, delayed diagnosis can result in permanent kidney damage, emphasizing why both healthcare providers and patients must remain vigilant about supplement safety.

Essential Takeaways:

- The syndrome is entirely preventable by limiting total calcium intake to 1000-1200 mg daily from all sources

- Calcium carbonate antacids (Tums, Rolaids) are the primary modern culprit

- Early warning signs include persistent constipation, unusual fatigue, increased thirst, and confusion

- Treatment is simple: stop calcium, provide IV hydration, and monitor closely

- Recovery is rapid and complete when caught early

- Prevention through patient education remains the best strategy

As medical knowledge advances and the population ages with increased osteoporosis awareness, the incidence of milk alkali syndrome may continue rising unless healthcare providers and patients remain vigilant about supplement safety. By understanding the pathophysiology, recognizing clinical presentations, distinguishing the syndrome from other hypercalcemic conditions, and implementing appropriate prevention strategies, we can protect patients from this entirely avoidable condition while still ensuring adequate calcium intake for bone health.

Ready to learn more about metabolic disorders and stay updated on important medical conditions? Visit Simply MBBS at simplymbbs.com for evidence-based articles on medicine, physical health, mental health, and MBBS exam preparation. Our student-led platform publishes clear, comprehensive content made simple for medical students, doctors, and curious readers worldwide.

Subscribe to our newsletter today to receive weekly updates featuring clinical pearls, exam tips, breaking medical news, and the latest insights designed specifically for healthcare professionals and students. Join thousands of learners who trust Simply MBBS for quality medical education. Your journey to medical excellence starts here—subscribe now and never miss critical updates on health topics that matter to your practice, studies, and patient care. Stay informed, stay ahead, and become part of our growing medical community dedicated to making complex medicine simple and accessible for everyone.