Every year, tragic headlines tell of mass casualties due to adulterated or homemade alcohol—cases that grip communities in both India and the United States. Behind these stories is a silent killer: methanol poisoning. Unlike ethanol, which is commonly found in alcoholic beverages, methanol is an industrial alcohol with devastating toxic potential. When consumed, whether knowingly or unknowingly, methanol can swiftly lead to blindness, organ failure, and death. For MBBS students, doctors, allied health professionals, and the general public, understanding the journey methanol takes through the body, the clinical signs it produces, and the right treatment strategies is not just academic—it’s lifesaving knowledge.

What is Methanol Poisoning?

Methanol poisoning occurs when a person ingests methanol, a clear, colorless liquid found in products like antifreeze, windshield washer fluid, and illicitly distilled spirits. Unlike ethanol, methanol itself is only moderately intoxicating; the real danger emerges once it is metabolized by the liver, producing highly toxic compounds—formaldehyde and formic acid. These metabolites disrupt cellular respiration, cause metabolic acidosis, and severely damage the optic nerve. Even a single mouthful can be fatal.

The Global Impact: Why Methanol Poisoning Matters

Methanol poisoning is both a medical and social emergency. In developing countries, where access to legitimate alcohol can be limited, methanol contamination in illegal spirits has led to catastrophic outbreaks. Even in developed nations, accidental ingestion due to chemical misuse remains a persistent risk. Mass incidents in northern India have claimed hundreds of lives, while the U.S. sees sporadic clusters each year, often linked to accidental methanol exposure. For healthcare professionals, rapid diagnosis and treatment can mean the difference between life, death, and lifelong disability.

Common Sources and Risk Factors

Most cases of methanol poisoning arise from three main sources:

- Illicit Liquor: Adulterated or homemade alcohol, where methanol is used to increase potency or as a byproduct of poor distillation.

- Industrial Products: Accidental ingestion of cleaning fluids, antifreeze, and laboratory solvents—often in children or substance abusers.

- Occupational Exposure: Workers in industries using methanol as a solvent, especially without adequate safety measures.

The highest-risk populations include young adults, children, persons with substance abuse disorders, and those living in areas where unregulated alcohol is sold.

Pathophysiology: How Methanol Damages the Body

The toxic effects of methanol stem from its conversion in the liver. Initially, alcohol dehydrogenase converts methanol to formaldehyde, which is swiftly processed by aldehyde dehydrogenase into formic acid. Formic acid is the star villain—it inhibits mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase, halting cellular energy production. This leads to the buildup of lactic acid and hydrogen ions, resulting in a high anion gap metabolic acidosis. Most critically, formic acid targets the optic nerve, causing visual disturbances and potential blindness. Without rapid intervention, multiorgan failure can follow.

Clinical Presentation: Signs and Symptoms

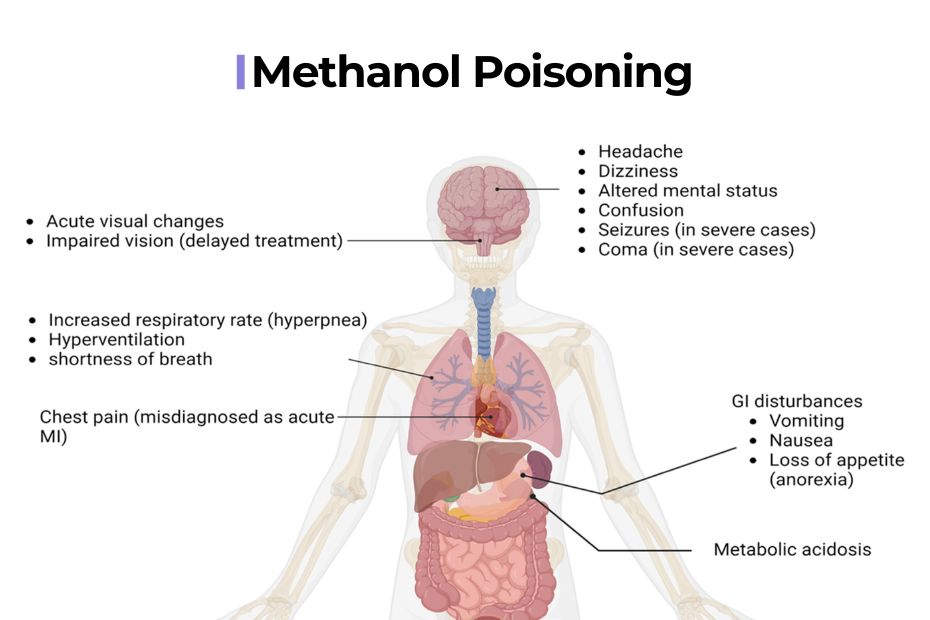

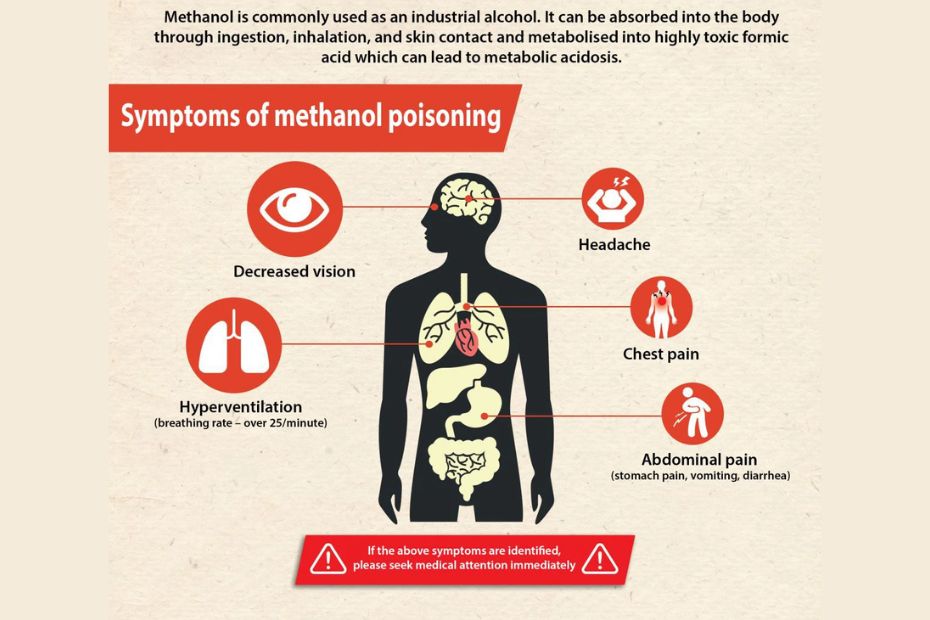

Symptoms of methanol poisoning often develop over several hours, as the body gradually metabolizes methanol.

- Early Signs: Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, dizziness.

- Neurological Effects: Headache, confusion, ataxia, drowsiness.

- Visual Disturbances: Blurred vision, photophobia, “snowfield” vision—a classic sign described as seeing through a fog or snowstorm.

- Severe Poisoning: Respiratory distress, hypotension, seizures, and eventually coma.

Prompt recognition of visual symptoms can be a crucial clue—unlike ethanol poisoning, methanol specifically targets the eyes.

Diagnosis: Approach for Clinicians

Diagnosis combines careful history, clinical suspicion, and laboratory testing.

- Blood Gas Analysis: Reveals high anion gap metabolic acidosis, low pH, and low bicarbonate.

- Osmol Gap Calculation: A key clue; elevated osmol gap indicates toxic alcohol ingestion.

- Serum Methanol Level: Direct measurement when available, with levels >20 mg/dL considered toxic.

- Fundoscopic Exam: Shows optic disc edema and hyperemia if the optic nerve is affected.

- Additional Labs: Renal function, electrolytes, and lactate help gauge severity.

Clinical pearl: Never dismiss unexplained metabolic acidosis with visual or neurological symptoms.

Management: Emergency Stabilization and Antidotes

Immediate stabilization is crucial.

- Airway, Breathing, Circulation: Secure, support, monitor for arrhythmias.

- Acidosis Correction: Sodium bicarbonate IV to maintain pH above 7.3.

-

Antidote Therapy:

-

Fomepizole (Preferred): Blocks alcohol dehydrogenase, preventing toxic metabolite formation.

-

Ethanol (If Fomepizole Unavailable): Competes for metabolism, but requires careful monitoring of blood levels to avoid ethanol toxicity.

-

-

Hemodialysis: Life-saving in severe cases (pH <7.2, visual symptoms, or methanol >50 mg/dL). Rapidly removes methanol and formic acid, correcting acidosis.

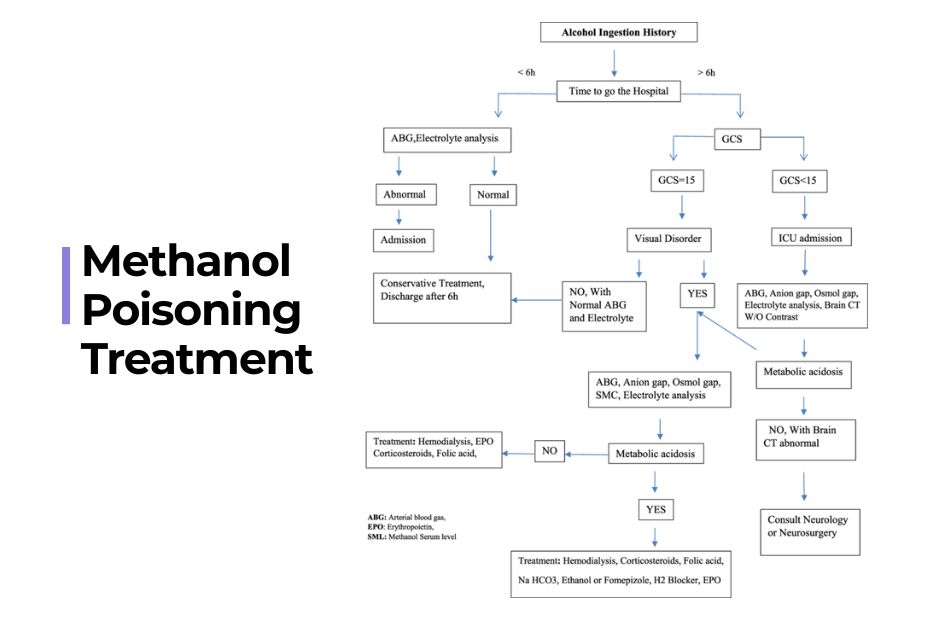

Treatment Algorithm: Practical Steps

- Confirm diagnosis based on history, labs, and clinical features.

- Start supportive therapy: IV fluids, correction of electrolytes.

- Begin antidote: Fomepizole or ethanol immediately—do not wait for lab confirmation.

- Initiate hemodialysis if criteria met.

- Monitor: Mental status, vision, and acid-base status persistently for at least 48 hours.

Case Study: Outbreak in India

In 2021, a mass methanol poisoning occurred in a rural Indian village. Victims presented to the ED with complaints of vomiting and progressive vision loss. Quick-thinking physicians suspected methanol toxicity, initiated fomepizole and hemodialysis, and reduced mortality from 25% to 8%. For survivors, vision returned in 70% of cases—a powerful testament to the lifesaving effect of prompt, evidence-based care.

Prevention and Public Health Strategies

Methanol poisoning can be prevented.

- Public education: Campaigns to warn about the dangers of illicit and homemade alcohol.

- Legal enforcement: Regular testing of commercially available spirits, stricter controls on industrial methanol sales.

- Occupational safety: Proper training, PPE and regulation for workers in methanol-related industries.

- Healthcare training: Toxicology emergency response drills for ED teams.

Such interventions have drastically reduced methanol fatalities in many regions.

University Exam-Style Question:

Question Stem:

A 35-year-old male is admitted to the emergency department 18 hours after consuming home-distilled alcohol. He complains of severe headache, vomiting, and blurred vision described as “seeing through fog.” On examination, he is drowsy with rapid breathing. Laboratory findings show: arterial blood pH 7.09; bicarbonate 7 mEq/L; serum methanol 65 mg/dL; anion gap 28.

Discuss the pathophysiology, clinical features, investigations, and stepwise management of methanol poisoning. Add a labeled metabolic pathway diagram, viva tips, and a quick exam checklist.

Detailed Model Answer:

Introduction

Methanol poisoning is a life-threatening emergency resulting from the ingestion of methanol—a toxic alcohol found in industrial products and sometimes illicit liquors. Unlike ethanol, methanol itself is not acutely intoxicating; its fatal potential lies in its hepatic metabolism to formic acid, which leads to profound acidosis and optic nerve injury. This answer outlines the pathophysiology, clinical features, diagnostic approach, and the evidence-based management protocol for methanol poisoning, with key focus areas for university exams.

Pathophysiology

After ingestion, methanol is rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and peaks in plasma within one hour. It undergoes hepatic oxidation in two main steps:

-

Step 1: Methanol → Formaldehyde

By alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) in the liver. -

Step 2: Formaldehyde → Formic Acid

By aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH).

Formic acid is the primary toxic metabolite. It inhibits mitochondrial enzyme cytochrome c oxidase, halting cellular respiration and ATP synthesis. This leads to anaerobic metabolism, lactic acid build-up, and a profound high-anion gap metabolic acidosis. Formic acid has a particular affinity for the optic nerve, causing demyelination and necrosis, manifesting as visual disturbances progressing to permanent blindness.

[Diagram Prompt]

Labelled pathway:

-

Methanol → (ADH) → Formaldehyde → (ALDH) → Formic Acid

-

Formic acid: (1) Inhibits mitochondrial function → acidosis, (2) Damages optic nerve → vision loss.

Clinical Features

Methanol poisoning manifests after a latent period of 6–24 hours (delayed symptoms due to slow metabolism), but faster if ethanol is not co-ingested.

1. GI and Neurologic Phase (6–12 hours):

- Nausea, vomiting, epigastric pain

- Headache, dizziness, drowsiness

2. Visual Toxicity Phase (12–18 hours):

- Blurred vision, photophobia

- “Snowfield” vision (classic: vision as if through a snowstorm)

- Dilated pupils, decreased visual acuity to complete blindness

3. Severe Poisoning (18–24+ hours):

- Kussmaul’s respiration (deep, rapid breathing from metabolic acidosis)

- Altered sensorium, seizures, coma

- Hypotension, acute tubular necrosis, multi-organ failure

Exam Pearl:

Persistent vomiting or any visual disturbance after alcohol ingestion—think methanol poisoning, not just ethanol intoxication!

Diagnostic Approach

1. Biochemical Labs:

-

Arterial Blood Gas (ABG):

Profound metabolic acidosis (low pH, low HCO₃⁻, high anion gap) -

Serum Methanol Level:

Diagnostic if >20 mg/dL, but therapy should not wait for results. -

Osmol Gap:

(Measured osmolality) – (Calculated osmolality: 2 × [Na⁺] + glucose/18 + BUN/2.8)

Osmol gap >10 mOsm/kg supports toxic alcohol ingestion.

2. Visual & Neurological Evaluation:

- Fundoscopy: Optic disc hyperemia or edema

- Serial vision assessments: To track progression and response

3. Additional tests:

- Renal function, electrolytes, lactate (prognostic)

- ECG to detect arrhythmias

Pitfall to Avoid:

Normal initial methanol level if delayed—methanol rapidly metabolized, but metabolites still toxic!

Management – Stepwise Protocol

A. Immediate Stabilization

- Airway, breathing, circulation

- High-flow oxygen (even if not hypoxic, as it helps metabolize formate)

B. Correct Metabolic Acidosis

- IV sodium bicarbonate (1-2 mEq/kg bolus, repeat as needed)

- Aim for pH >7.3

C. Specific Antidotes

-

Fomepizole (preferred):

-

Loading 15 mg/kg IV; then 10 mg/kg q12h

-

Inhibits ADH, stopping methanol metabolism

-

-

Ethanol (if fomepizole unavailable):

-

Loading 10 mL/kg 10% ethanol IV

-

Titrate infusion to maintain blood ethanol 100–150 mg/dL (out-competes methanol for ADH)

-

D. Indications for Hemodialysis

- Severe acidosis (pH <7.25 or HCO₃⁻ <15)

- Visual symptoms

- Serum methanol >50 mg/dL

- Deterioration despite therapy

- Procedure: Continue until methanol <20 mg/dL, acidosis resolves, and symptoms improve

E. Supportive Care

- Electrolyte correction

- Renal and hepatic monitoring

- Seizure control if required

Practical Tip for Exams:

Start fomepizole/ethanol IMMEDIATELY on suspicion—do not wait for labs!

Prognosis

If treatment is early (within 24 hours), most patients survive with little or no sequelae. Delay in therapy results in irreversible blindness or death in up to 40–60%.

Viva Tips

- List methanol sources: industrial solvents, illicit liquor, antifreeze.

- 1st clinical clue: Visual change after alcohol ingestion.

- Key enzyme target: ADH (antidotes block this).

- Best test for diagnosis: High anion gap acidosis with high osmol gap.

- Indications for dialysis: severe acidosis, vision loss, methanol >50 mg/dL.

Last-Minute Checklist

- Check ABG and electrolytes

- Calculate anion and osmol gaps

- Assess fundus for optic neuropathy

- Antidote ready: Fomepizole/Ethanol

- Prepare for dialysis if severe

- Monitor vitals, urine output, vision

- Educate patient/family on risks of illicit alcohol

Diagram

Methanol [CH₃OH] | | (Alcohol Dehydrogenase) v Formaldehyde [HCHO] | | (Aldehyde Dehydrogenase) v Formic Acid [HCOOH] | -- Inhibits Cytochrome c Oxidase --> Cellular hypoxia, lactic acidosis -- Optic nerve damage --> Visual failure

Conclusion

Methanol poisoning is a medical and social tragedy, but with high suspicion and immediate intervention (antidote and dialysis), blindness, organ failure, and mortality can be drastically reduced. For exams and practice: Recognize early visual complaints, correct acidosis, use antidotes without delay, and dialyze aggressively when criteria are met.

This comprehensive model answer covers all essential exam points and clinical pearls on methanol poisoning. Use structured paragraphing, add a hand-drawn diagram if possible, and highlight management priorities for extra marks!

Comparing Methanol and Ethylene Glycol Poisoning

While both methanol and ethylene glycol are toxic alcohols, only methanol poses a distinct risk for vision loss. Ethylene glycol poisoning causes kidney damage, calcium oxalate crystal deposition, and severe acidosis but eye symptoms are rare. Similar antidote strategies apply, but clinical focus differs—rapid visual changes point to methanol, renal failure suggests ethylene glycol.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Many lives are lost because:

- Clinicians wait for lab confirmation before starting antidotes.

- Early symptoms are misattributed to ethanol or simple gastroenteritis.

- Ethanol infusions are used without frequent monitoring, causing further complications.

- Outbreak victims are not screened systematically—community awareness is key.

Avoiding these errors requires vigilance, suspicion, and immediate action.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1. Can home remedies treat methanol poisoning?

No—medical intervention is essential. Delaying antidotes or dialysis can result in blindness and death.

Q2. Is blindness from methanol reversible?

If treated within 24–48 hours, vision may return. Delays lead to permanent optic nerve damage.

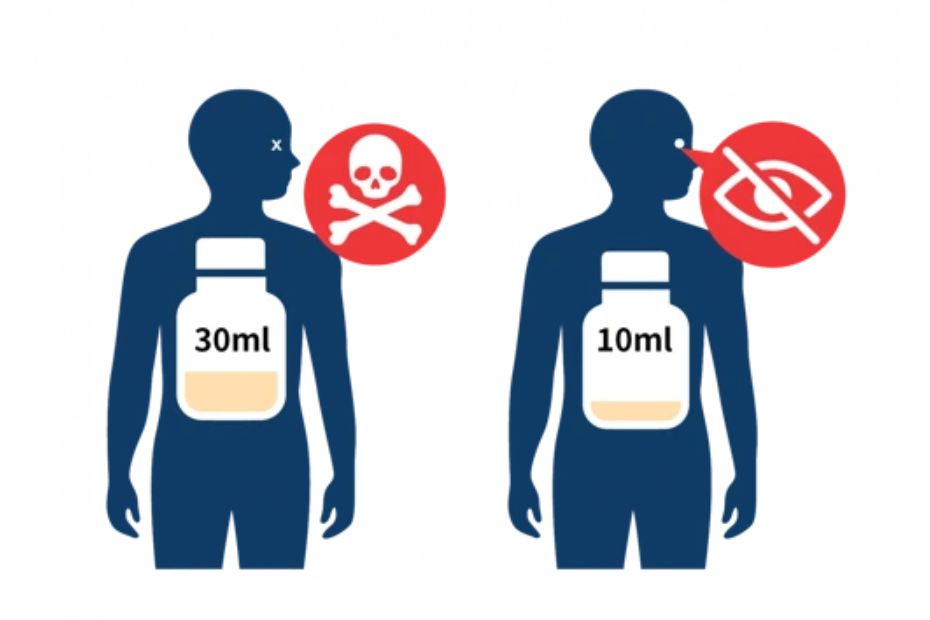

Q3. What is the safe amount of methanol?

Any ingestion should be treated as dangerous. Doses as low as 10 mL can result in toxicity.

Q4. Can ethanol found in drinks protect against methanol poisoning?

Not reliably. Medical-grade ethanol infusions are calculated and monitored for therapeutic effect.

Q5. How do hospitals monitor progress?

Serial blood gases, electrolytes, osmol gap, and visual status checks every few hours.

Latest Insights and Data-Driven Statistics

Data shows that in regions with rapid access to antidotes and dialysis, mortality for methanol poisoning drops below 10%. Public education campaigns can prevent up to 70% of outbreaks. Collaborative networks between poison control centers and emergency departments have reduced time-to-treatment by up to 50%—a crucial factor for survival.

The Role of Simply MBBS and Reliable Medical Sources

Simply MBBS is dedicated to producing clear, evidence-based guides on toxicology and acute medicine. Students, clinicians, and the public benefit from our straightforward explanations, exam notes, and Q&A formats. We back our guidance with citations from NCBI PMC and MedlinePlus, ensuring up-to-date, trustworthy advice (read more at simplymbbs.com/metabolic-acidosis and simplymbbs.com/iron-poisoning).

Conclusion

Methanol poisoning should always be considered in patients with unexplained metabolic acidosis and visual complaints—especially after suspected alcohol consumption. Early diagnosis, timely antidote therapy, and hemodialysis save lives and sight. Healthcare professionals, students, and community leaders must champion awareness and rapid response.

For exclusive medical guides, step-wise notes for MBBS exams, and updates on critical care, bookmark Simply MBBS. Subscribe to our newsletter for expert tips and deeper dives—where lifesaving knowledge meets exam success and clinical excellence