Understanding heart failure: classification, diagnosis & MBBS notes is essential for medical students, doctors, and anyone interested in cardiovascular health. Heart failure affects millions worldwide and represents a critical challenge in modern medicine. This comprehensive guide breaks down everything you need to know about heart failure classification systems, diagnostic approaches, and practical clinical applications—perfect for acing your exams and understanding real-world cardiology.

What is Heart Failure?

Heart failure (HF) is a complex clinical syndrome that occurs when the heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the body’s metabolic demands, or it can only do so at elevated filling pressures. According to standard medical textbooks like Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine and Braunwald’s Heart Disease, heart failure: classification, diagnosis & MBBS notes encompasses a progressive condition where structural or functional cardiac abnormalities lead to reduced cardiac output and/or increased intracardiac pressures.

The condition is not simply “heart failure” in the literal sense—the heart continues beating but cannot adequately supply oxygen-rich blood to tissues. This results in characteristic symptoms like shortness of breath, fatigue, and fluid retention.

Key Definition Points

Heart failure manifests when the heart muscle becomes damaged, overloaded, or stiff, leading to inefficient pumping. The Universal Definition of Heart Failure requires three components:

- Symptoms and/or signs of heart failure (dyspnea, fatigue, edema)

- Structural and/or functional cardiac abnormalities

- Elevated natriuretic peptides OR objective evidence of pulmonary or systemic congestion

Why Heart Failure: Classification, Diagnosis & MBBS Notes Matters

Understanding heart failure classification is crucial for several reasons:

- For Medical Students: Heart failure is a high-yield topic in university exams, NEET-PG, and clinical rotations. Mastering classification systems helps you answer pattern-based questions and understand treatment algorithms.

- For Clinicians: Proper classification guides treatment decisions. A patient with HFrEF receives entirely different medications than someone with HFpEF. The 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guidelines emphasize that classification determines guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT).

- For Patients and Families: Knowing whether your loved one has Stage B or Stage C heart failure helps you understand prognosis, treatment intensity, and lifestyle modifications needed.

- Clinical Significance: Heart failure carries significant mortality—approximately 10% annual death rate overall, with 5-year survival around 50%. Early diagnosis and proper classification improve outcomes dramatically.

Heart Failure Classification Systems

Two major classification systems dominate modern cardiology: the ACC/AHA Staging System and the NYHA Functional Classification.

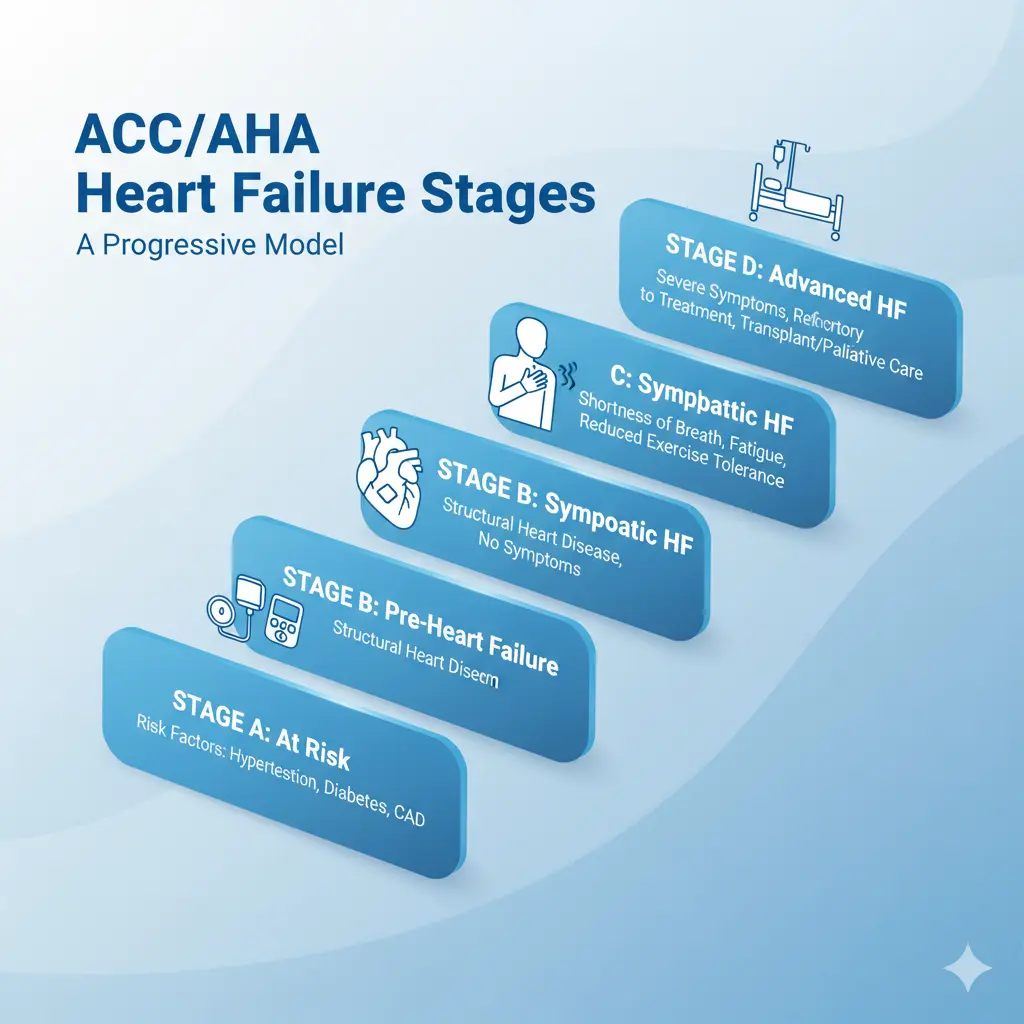

ACC/AHA Stages of Heart Failure

The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association developed a staging system that recognizes heart failure as a progressive disease:

| Stage | Description | Key Features | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage A | At risk for HF | No structural disease, no symptoms, but risk factors present | Hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, family history of cardiomyopathy, exposure to cardiotoxic drugs |

| Stage B | Pre-HF | Structural heart disease present, but no HF symptoms | Previous MI, reduced LVEF, LV hypertrophy, valvular disease, elevated biomarkers without symptoms |

| Stage C | Symptomatic HF | Structural disease WITH current or past HF symptoms | Dyspnea, fatigue, reduced exercise tolerance with structural abnormalities |

| Stage D | Advanced HF | Severe symptoms despite maximal therapy, recurrent hospitalizations | Refractory symptoms interfering with daily life, requiring advanced interventions |

Important Clinical Note: The ACC/AHA stages are progressive and irreversible—once you reach Stage C, you cannot return to Stage B even with treatment. However, ejection fraction can improve with therapy.

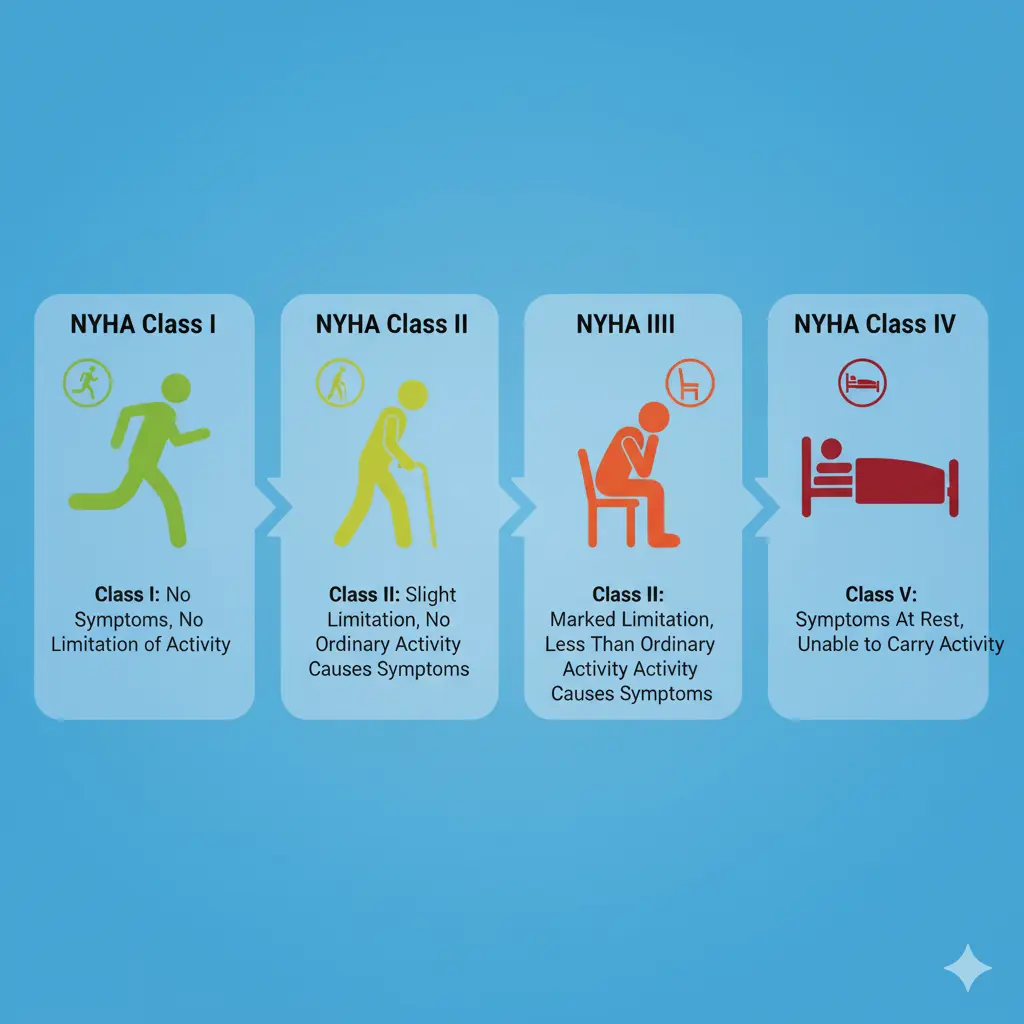

NYHA Functional Classification

The New York Heart Association classification assesses functional limitations based on physical activity tolerance:

| NYHA Class | Symptoms | Physical Activity Limitation | Metabolic Equivalents (METs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | No symptoms with ordinary activity | No limitation—ordinary activity does not cause fatigue, palpitation, or dyspnea | ≥7 METs (can climb stairs, jog) |

| Class II | Symptoms with ordinary activity | Slight limitation—comfortable at rest, but ordinary activity causes symptoms | 5-7 METs (can walk briskly, light housework) |

| Class III | Symptoms with minimal activity | Marked limitation—less than ordinary activity causes symptoms | 2-5 METs (can dress self, walk slowly) |

| Class IV | Symptoms at rest | Unable to perform any activity without discomfort, symptoms present at rest | <2 METs (symptoms with all activities) |

Key Difference: NYHA classification can change with treatment—a patient can improve from Class III to Class II with proper therapy, unlike ACC/AHA stages.

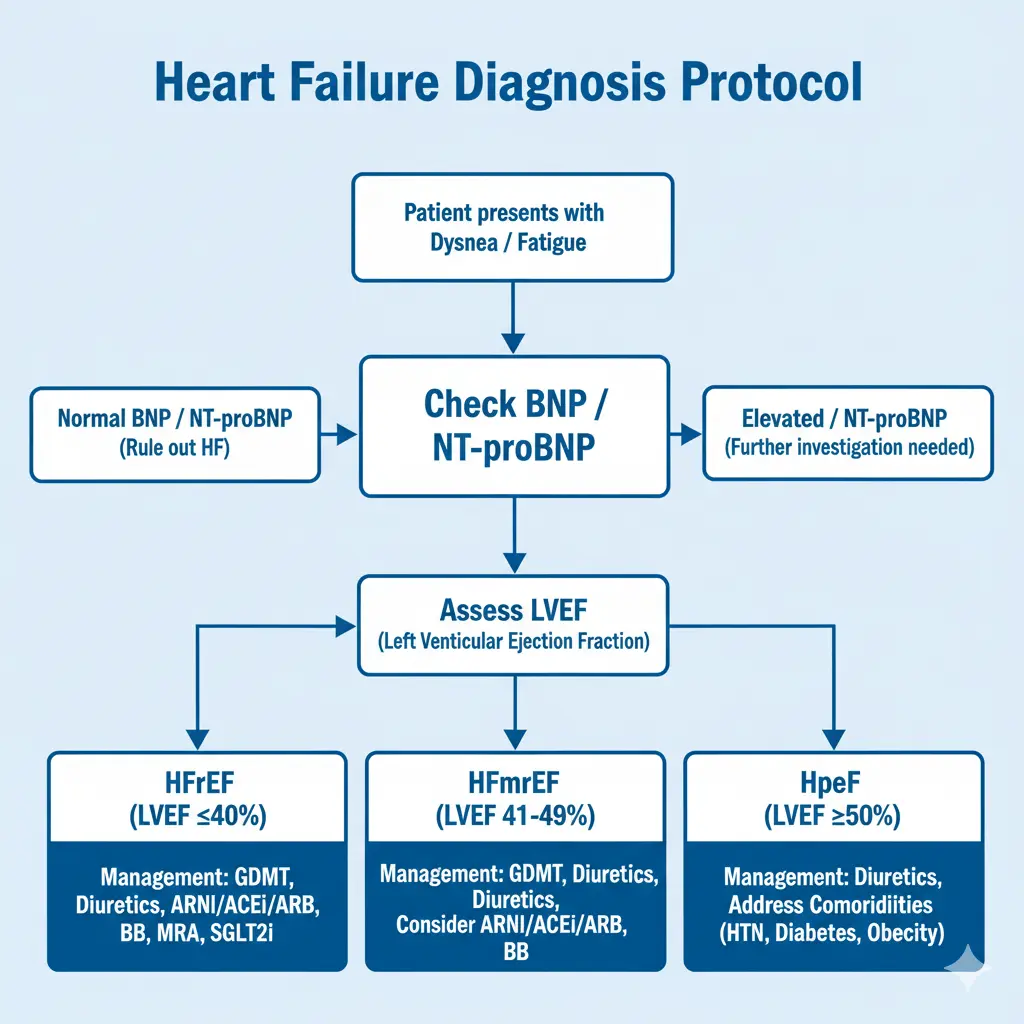

Classification by Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction (LVEF)

Modern heart failure diagnosis categorizes patients by ejection fraction:

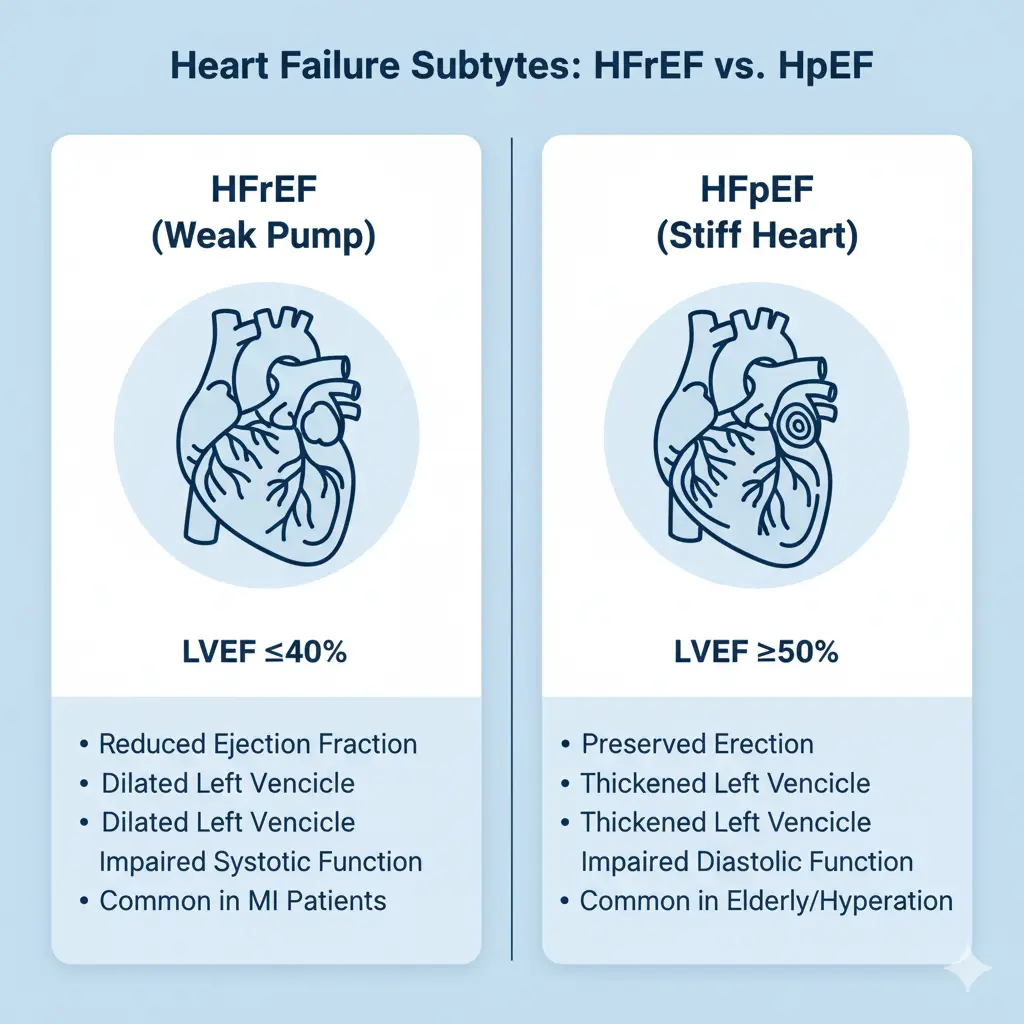

HFrEF (Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction)

- LVEF ≤40%

- Previously called “systolic heart failure”

- Most common after myocardial infarction

- Strong evidence for GDMT benefit

HFmrEF (Heart Failure with Mildly Reduced Ejection Fraction)

- LVEF 41-49%

- Intermediate category added in recent guidelines

- Shares features of both HFrEF and HFpEF

- Requires evidence of elevated filling pressures or biomarkers

HFpEF (Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction)

- LVEF ≥50%

- Previously called “diastolic heart failure”

- Common in elderly, hypertension, women

- Requires evidence of structural/functional abnormalities

HFimpEF (Heart Failure with Improved Ejection Fraction)

- Current LVEF >40% with previously documented LVEF ≤40%

- Important to recognize—these patients still have heart failure

- Should continue most HF medications

Pathophysiology: How Heart Failure Develops

Understanding the mechanisms behind heart failure helps with both exam answers and clinical reasoning.

Primary Mechanisms

1. Myocardial Dysfunction

The heart muscle loses contractile function due to injury, overload, or infiltration. Myocytes show decreased myosin heavy chain expression, loss of myofilaments, and altered calcium handling.

2. Hemodynamic Abnormalities

In HFrEF: The ventricle contracts poorly, leading to increased end-systolic volume, decreased ejection fraction, and reduced stroke volume.

In HFpEF: The ventricle becomes stiff, impairing relaxation and filling. This increases filling pressures despite normal ejection fraction.

3. Neurohormonal Activation

Compensatory mechanisms become maladaptive:

-

Sympathetic nervous system: Increases heart rate and contractility but causes arrhythmias and myocyte toxicity

-

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS): Causes vasoconstriction, sodium retention, and cardiac remodeling

-

Vasopressin (ADH): Increases water retention, worsening congestion

4. Cardiac Remodeling

Progressive changes in heart structure:

-

Chamber dilation: Ventricles enlarge

-

Wall thinning or hypertrophy: Depending on type of stress

-

Extracellular matrix changes: Fibrosis develops via matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)

-

Myocyte changes: Cell death, slippage, and dysfunction

Frank-Starling Mechanism Failure

In healthy hearts, increased filling (preload) improves contractility. In heart failure, the ventricle operates beyond optimal stretch, and the Frank-Starling curve flattens—more filling doesn’t improve output and may worsen pulmonary congestion.

Causes and Risk Factors of Heart Failure

Major Causes

Coronary Artery Disease: The leading cause in developed nations. Narrowed arteries reduce oxygen supply, weakening heart muscle. Previous heart attacks leave scarred, non-contractile tissue.

Hypertension: Chronic high blood pressure forces the heart to work harder, leading to left ventricular hypertrophy and eventual dysfunction. Doubles HF risk.

Valvular Heart Disease: Stenotic or regurgitant valves create volume or pressure overload.

Cardiomyopathies:

- Dilated cardiomyopathy: Enlarged, weakened heart chambers

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: Thickened walls impair filling

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy: Stiff heart muscle

Myocarditis: Viral or inflammatory damage to heart muscle.

Cardiotoxic Medications: Chemotherapy agents (anthracyclines), some diabetes drugs (thiazolidinediones).

Key Risk Factors

- Age >65 years

- Diabetes mellitus (triples risk)

- Obesity and metabolic syndrome

- Chronic kidney disease

- Sleep apnea

- Alcohol abuse

- Smoking

- Arrhythmias (especially atrial fibrillation)

Heart Failure Diagnosis: Clinical Approach

Diagnosing heart failure requires integrating history, physical examination, biomarkers, and imaging.

Clinical History and Symptoms

Cardinal Symptoms (FACES Mnemonic):

- Fatigue: Reduced oxygen delivery causes tiredness

- Activity limitation: Exercise intolerance, reduced functional capacity

- Congestion: Pulmonary edema causes dyspnea, cough, wheezing

- Edema: Ankle swelling, weight gain from fluid retention

- Shortness of breath: Dyspnea on exertion, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea

Additional Symptoms:

- Nocturnal cough

- Nocturia (nighttime urination)

- Chest discomfort

- Confusion (in advanced HF)

- Anorexia

Physical Examination Findings

Cardiovascular Signs:

- Elevated jugular venous pressure (JVP): >4-5 cm above sternal angle (90% specificity, 30% sensitivity)

- Third heart sound (S3 gallop): Pathognomonic for heart failure

- Displaced apex beat: Indicates left ventricular dilation

- Tachycardia: Compensatory mechanism

- Hypotension: Poor prognostic sign if <90-100 mmHg

- Heart murmurs: Suggest valvular disease

Respiratory Signs:

- Bibasal crackles: Pulmonary edema

- Tachypnea: Increased respiratory rate

- Pleural effusion: Dullness to percussion

Other Signs:

- Peripheral edema: Ankle/leg swelling

- Hepatomegaly: Enlarged, tender liver

- Ascites: Fluid in abdomen

- Cachexia: Muscle wasting in advanced HF

Framingham Diagnostic Criteria

The Framingham criteria remain widely used for heart failure diagnosis. Requires 2 major criteria OR 1 major + 2 minor criteria:

Major Criteria:

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea or orthopnea

- Jugular venous distension

- Rales (crackles)

- Cardiomegaly on chest X-ray

- Acute pulmonary edema

- S3 gallop

- Hepatojugular reflux

Minor Criteria:

- Ankle edema

- Nocturnal cough

- Dyspnea on exertion

- Hepatomegaly

- Pleural effusion

- Tachycardia (>120 bpm)

Diagnostic Performance: Framingham criteria show 97% sensitivity for systolic HF and 89% for diastolic HF, with strong rule-out ability (LR- = 0.04-0.1).

Diagnostic Tests for Heart Failure

Biomarkers: BNP and NT-proBNP

B-type natriuretic peptides are the most valuable biomarkers for heart failure diagnosis.

What They Are: Hormones released by stressed heart ventricles in response to pressure/volume overload.

Diagnostic Cutoffs:

| Test | Rule Out HF | Possible HF | High Probability HF |

|---|---|---|---|

| BNP | <100 pg/mL | 100-400 pg/mL | >400 pg/mL |

| NT-proBNP (age-adjusted) | <300 pg/mL | 300-900 pg/mL | >900 pg/mL (age <50) >1800 pg/mL (age >75) |

Clinical Use:

- Excellent for ruling out HF: Normal levels make HF unlikely

- Correlates with severity: Higher levels indicate worse NYHA class

- Prognostic value: Predicts mortality and hospitalization risk

- Monitors treatment: Reduction indicates improvement

Limitations:

- Elevated in: Renal failure, pulmonary embolism, sepsis, atrial fibrillation, elderly patients

- Lower in: Obesity (falsely reassuring)

- Some HFpEF patients have normal levels despite confirmed HF

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

Key Findings in Heart Failure:

- Sinus tachycardia

- Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH)

- Q waves (prior myocardial infarction)

- Left bundle branch block (LBBB)

- Atrial fibrillation

- Prolonged QRS (>120 ms suggests need for cardiac resynchronization therapy)

Important: A normal ECG makes heart failure unlikely (negative predictive value >90%).

Chest X-Ray

Classic Findings:

- Cardiomegaly (cardiothoracic ratio >0.5)

- Pulmonary congestion/edema

- Pleural effusions (usually bilateral)

- Kerley B lines (interstitial edema)

- Redistribution of pulmonary vessels

Echocardiography: The Gold Standard

Echocardiography is the most important test for confirming heart failure diagnosis and determining type.

Key Measurements:

- Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): Defines HF subtype (normal: 55-70%)

- Left ventricular dimensions: LVEDD (end-diastolic dimension), volumes

- Wall motion abnormalities: Suggest ischemic etiology

- Valvular function: Identifies valve disease

- Diastolic parameters: E/e’ ratio, left atrial size

-

-

E/e’ >13-15 suggests elevated filling pressures

-

-

Global longitudinal strain (GLS): Sensitive marker of dysfunction

- Normal: <-16%

- Reduced GLS predicts outcomes even with normal LVEF

HFpEF-Specific Findings:

- Preserved LVEF (≥50%)

- Left atrial enlargement (LAVi >28 mL/m²)

- Left ventricular hypertrophy (increased LV mass index)

- Elevated E/e’ ratio

- Pulmonary hypertension (elevated PASP)

Additional Tests

Blood Tests:

- Complete blood count (anemia worsens HF)

- Renal function (creatinine, eGFR)

- Electrolytes (Na+, K+)

- Liver function tests

- Thyroid function (TSH)

- Lipid profile

- Cardiac troponin (if ACS suspected)

- Hemoglobin A1c (diabetes screening)

Advanced Imaging:

- Cardiac MRI: Detailed tissue characterization, fibrosis assessment, helps distinguish HF causes

- Cardiac catheterization: Measures filling pressures directly, evaluates coronary arteries

- Stress testing: Assesses ischemia, functional capacity

Differential Diagnosis: Heart Failure Mimics

Many conditions present similarly to heart failure. Key differentials include:

Pulmonary Causes:

- COPD/Asthma: Most common HF mimic

- Pneumonia: Infectious infiltrate

- Pulmonary embolism: Acute dyspnea, chest pain

- Interstitial lung disease: Chronic progressive dyspnea

Renal Causes:

- Acute kidney injury: Fluid overload

- Nephrotic syndrome: Hypoalbuminemia causing edema

- Chronic kidney disease: Volume overload

Hepatic:

-

Cirrhosis: Ascites, edema from portal hypertension

Cardiac (Non-HF):

- Pericardial disease: Constrictive pericarditis, tamponade

- Valvular disease: Without myocardial dysfunction

- High-output states: Severe anemia, thyrotoxicosis

How to Differentiate:

- BNP/NT-proBNP levels (very low in non-cardiac causes)

- Echocardiography shows normal cardiac function

- Clinical context and risk factors

- Response to diuretics (effective in HF, less in other causes)

Treatment Overview: Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy (GDMT)

Modern heart failure treatment for HFrEF centers on “quadruple therapy”:

The Four Pillars of HFrEF Treatment

1. ARNI (Angiotensin Receptor-Neprilysin Inhibitor)

- Sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto)

- Reduces mortality and hospitalizations

- Preferred over ACE-I/ARB

2. Beta-Blockers

- Carvedilol, metoprolol succinate, bisoprolol

- Reduce mortality, improve LVEF

3. Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonists (MRA)

- Spironolactone, eplerenone

- Reduce mortality in symptomatic HF

4. SGLT2 Inhibitors

- Dapagliflozin, empagliflozin

- Newest addition, reduce hospitalizations

- Benefit regardless of diabetes status

Additional Therapies:

- Loop diuretics (furosemide) for congestion

- Ivabradine (if heart rate >70 in sinus rhythm)

- Hydralazine-nitrate combination (especially for African Americans)

- Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) for LBBB with QRS >130 ms

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) for ischemic cardiomyopathy

Lifestyle Modifications

Essential for All HF Patients:

- Sodium restriction: <2-3 grams/day

- Fluid monitoring: Daily weights, report 2-3 lb gain in 1 day or 5 lb in 1 week

- Regular exercise: Cardiac rehabilitation improves outcomes

- Smoking cessation: Mandatory

- Limit alcohol: Maximum 14 units/week, or abstain if alcohol-related cardiomyopathy

- Vaccinations: Annual influenza, one-time pneumococcal

- Medication adherence: Critical for preventing exacerbations

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Students:

- Confusing ACC/AHA stages with NYHA classes: Remember, stages progress A→D and never reverse; NYHA classes can improve

- Forgetting HFmrEF category: Recent guidelines added this intermediate group (LVEF 41-49%)

- Assuming normal BNP rules out HFpEF: Some HFpEF patients have normal peptides

- Not checking ECG first: If normal, HF is unlikely

For Clinicians:

- Stopping GDMT when EF improves: HFimpEF patients still need treatment

- Using thiazide diuretics alone: Loop diuretics are preferred for HF

- Missing diuretic resistance: May need combination therapy or higher doses

- Not uptitrating medications: Target or maximally tolerated doses crucial

For Patients:

- Not monitoring daily weights: Early indicator of worsening

- Consuming high-sodium foods: Hidden salt in processed foods

- Stopping medications when feeling better: Recipe for decompensation

- Ignoring early warning signs: Prompt reporting prevents hospitalizations

FAQs About Heart Failure

Q1: What’s the difference between HFrEF and HFpEF?

HFrEF (reduced ejection fraction ≤40%) involves poor pumping—the heart doesn’t squeeze effectively. HFpEF (preserved ejection fraction ≥50%) involves poor filling—the heart is too stiff to relax. Think of HFrEF as a “weak heart” and HFpEF as a “stiff heart.”

Q2: Can heart failure be cured?

Heart failure is typically a chronic, progressive condition without a cure. However, some reversible causes (alcohol-related, peripartum cardiomyopathy, tachycardia-induced) can resolve with treatment. Most patients require lifelong management, though ejection fraction can improve.

Q3: What BNP level indicates heart failure?

BNP >400 pg/mL or NT-proBNP >900 pg/mL (adjusted for age) strongly suggests heart failure. However, levels <100 pg/mL (BNP) or <300 pg/mL (NT-proBNP) effectively rule out HF.

Q4: How long can you live with heart failure?

Prognosis varies by severity. Five-year survival averages around 50%, but this improves dramatically with modern GDMT. Stage A/B patients have better outcomes than Stage C/D. Early diagnosis and adherence to treatment are crucial.

Q5: What’s the most important test for diagnosing heart failure?

Echocardiography is the gold standard—it confirms diagnosis, determines HF type (HFrEF vs HFpEF), identifies causes, and guides treatment. However, BNP/NT-proBNP are excellent initial screening tests.

Q6: Can you have heart failure with a normal ejection fraction?

Yes—this is called HFpEF (heart failure with preserved ejection fraction). It accounts for approximately 50% of all HF cases and is especially common in elderly patients, women, and those with hypertension.

Q7: What are the early warning signs of worsening heart failure?

Watch for: sudden weight gain (2-3 lbs in a day), increased swelling, worsening shortness of breath, inability to lie flat, reduced exercise tolerance, persistent cough, and increased fatigue. Report these to your doctor immediately.

Exam Question–Answer (University Pattern)

Question 1: Short Answer (10 Marks)

Q: A 65-year-old man presents with progressive dyspnea on exertion over 3 months. He has a history of myocardial infarction 2 years ago. On examination, his BP is 100/70 mmHg, pulse 98 bpm, bilateral basal crackles are present, and there is ankle edema. His NT-proBNP is 1500 pg/mL.

a) What is the most likely diagnosis? (2 marks)

b) Outline the classification of this condition based on LVEF. (4 marks)

c) List four investigations you would order and their rationale. (4 marks)

Model Answer:

a) Diagnosis (2 marks):

- Heart failure (most likely HFrEF given history of MI)

- Post-myocardial infarction cardiomyopathy

b) Classification by LVEF (4 marks):

- HFrEF: LVEF ≤40% (1 mark) – Most common post-MI, responds to GDMT

- HFmrEF: LVEF 41-49% (1 mark) – Intermediate category with mixed features

- HFpEF: LVEF ≥50% (1 mark) – Preserved systolic function, diastolic dysfunction

- HFimpEF: Previous LVEF ≤40% now improved to >40% with treatment (1 mark)

c) Investigations (4 marks):

- Echocardiography (1 mark): Gold standard to assess LVEF, wall motion abnormalities, valve function, and diastolic parameters

- ECG (1 mark): Check for arrhythmias, Q waves (prior MI), LBBB, LVH

- Chest X-ray (1 mark): Assess cardiomegaly, pulmonary congestion, pleural effusions

- Renal function & electrolytes (1 mark): Baseline before starting GDMT, assess for renal dysfunction affecting prognosis

Question 2: Long Answer (20 Marks)

Q: Discuss the ACC/AHA staging system and NYHA functional classification for heart failure. How do these systems complement each other in clinical practice?

Model Answer Structure:

Introduction (2 marks):

- Two main classification systems used complementarily

- ACC/AHA stages describe disease progression (structural)

- NYHA classes describe functional capacity (symptoms)

ACC/AHA Stages (6 marks):

- Stage A: At-risk patients (hypertension, diabetes, CAD, family history) – no structural disease or symptoms

- Stage B: Pre-HF with structural disease (previous MI, reduced LVEF, LVH) but asymptomatic

- Stage C: Symptomatic HF with structural abnormalities

- Stage D: Advanced/refractory HF despite maximal therapy

- Emphasize progressive, irreversible nature

- Guides prevention strategies and treatment intensity

NYHA Functional Classification (6 marks):

- Class I: No symptoms, no limitation

- Class II: Symptoms with ordinary activity, slight limitation

- Class III: Symptoms with minimal activity, marked limitation

- Class IV: Symptoms at rest, unable to perform any activity

- Reversible with treatment—patients can move between classes

- Correlates with exercise capacity (METs)

Clinical Complementarity (4 marks):

- Stages guide what to treat (prevention vs symptomatic therapy)

- NYHA guides intensity of treatment and functional prognosis

- Example: Stage C, NYHA Class II receives full GDMT but has better functional status than Stage C, NYHA Class IV

- Stages determine trial eligibility, transplant consideration

Conclusion (2 marks):

- Both systems essential for comprehensive HF assessment

- Together provide structural and functional evaluation

- Guide evidence-based treatment decisions

Question 3: OSCE Station/Viva Tips (5 Marks)

Common Viva Questions:

Q: “What are the components of the Framingham criteria?”

A: Need 2 major OR 1 major + 2 minor criteria. Majors: PND/orthopnea, JVD, rales, cardiomegaly, acute pulmonary edema, S3, hepatojugular reflux. Minors: ankle edema, nocturnal cough, DOE, hepatomegaly, pleural effusion, tachycardia >120.

Q: “How would you differentiate HFrEF from HFpEF at the bedside?”

A: Both present similarly clinically. Key difference: Echocardiography shows LVEF ≤40% in HFrEF vs ≥50% in HFpEF. HFpEF more common in elderly, women, hypertensives; HFrEF more common post-MI. Treatment differs significantly.

Q: “What is the quadruple therapy for HFrEF?”

A: (1) ARNI (sacubitril/valsartan), (2) Beta-blocker, (3) MRA (spironolactone), (4) SGLT2 inhibitor—all together reduce mortality and hospitalizations.

Last-Minute Checklist for Exams

Must Remember:

- ✓ ACC/AHA Stages: A (at risk) → B (pre-HF) → C (symptomatic) → D (advanced) – irreversible

- ✓ NYHA Classes: I (no symptoms) → IV (rest symptoms) – reversible

- ✓ LVEF cutoffs: ≤40% (HFrEF), 41-49% (HFmrEF), ≥50% (HFpEF)

- ✓ BNP cutoffs: <100 rules out, >400 highly suggestive

- ✓ Framingham: 2 major OR 1 major + 2 minor

- ✓ S3 gallop = pathognomonic for HF

- ✓ Normal ECG makes HF unlikely

- ✓ Echo = gold standard diagnostic test

- ✓ Quadruple therapy for HFrEF (ARNI, BB, MRA, SGLT2i)

- ✓ Frank-Starling curve flattens in HF

Quick Diagram Prompt for Practice:

“Draw and label: (1) Frank-Starling curves comparing normal heart vs HF; (2) Flow chart for HF diagnostic approach starting with symptoms; (3) ACC/AHA stages as progressive boxes A→B→C→D”

Conclusion

Mastering heart failure: classification, diagnosis & MBBS notes requires understanding multiple classification systems, diagnostic approaches, and treatment principles. The ACC/AHA staging system and NYHA functional classification work together to provide comprehensive patient assessment. Modern diagnosis relies on clinical evaluation, biomarkers (especially BNP/NT-proBNP), and echocardiography as the gold standard. With proper classification, we can deliver targeted, evidence-based treatments—particularly the quadruple therapy for HFrEF—that dramatically improve outcomes.

Whether you’re an MBBS student preparing for exams, a healthcare professional refining clinical skills, or someone seeking to understand this complex condition, remember: early recognition and appropriate management save lives. Heart failure may be chronic, but with modern therapies and lifestyle modifications, patients can achieve excellent quality of life and longevity.

Ready to learn more about cardiovascular medicine and ace your medical exams? Subscribe to the Simply MBBS newsletter for weekly updates on high-yield medical topics, exam tips, clinical pearls, and evidence-based practice guides. We make complex medicine simple—because your education matters.

Join thousands of medical students and doctors who trust Simply MBBS for clear, accurate, and exam-focused medical content. Visit simplymbbs.com today and explore our comprehensive libra