Diabetic Ketoacidosis is a life-threatening metabolic emergency that requires immediate recognition and treatment. This acute complication of diabetes mellitus affects thousands of patients annually and remains one of the leading causes of hospitalization among diabetic individuals. Whether you are an MBBS student preparing for exams, a practicing physician managing acute cases, or someone seeking to understand this critical condition, this comprehensive guide provides everything you need to know about Diabetic Ketoacidosis diagnosis, pathophysiology, and evidence-based management protocols.

What is Diabetic Ketoacidosis?

Standard Medical Definition of Diabetic Ketoacidosis

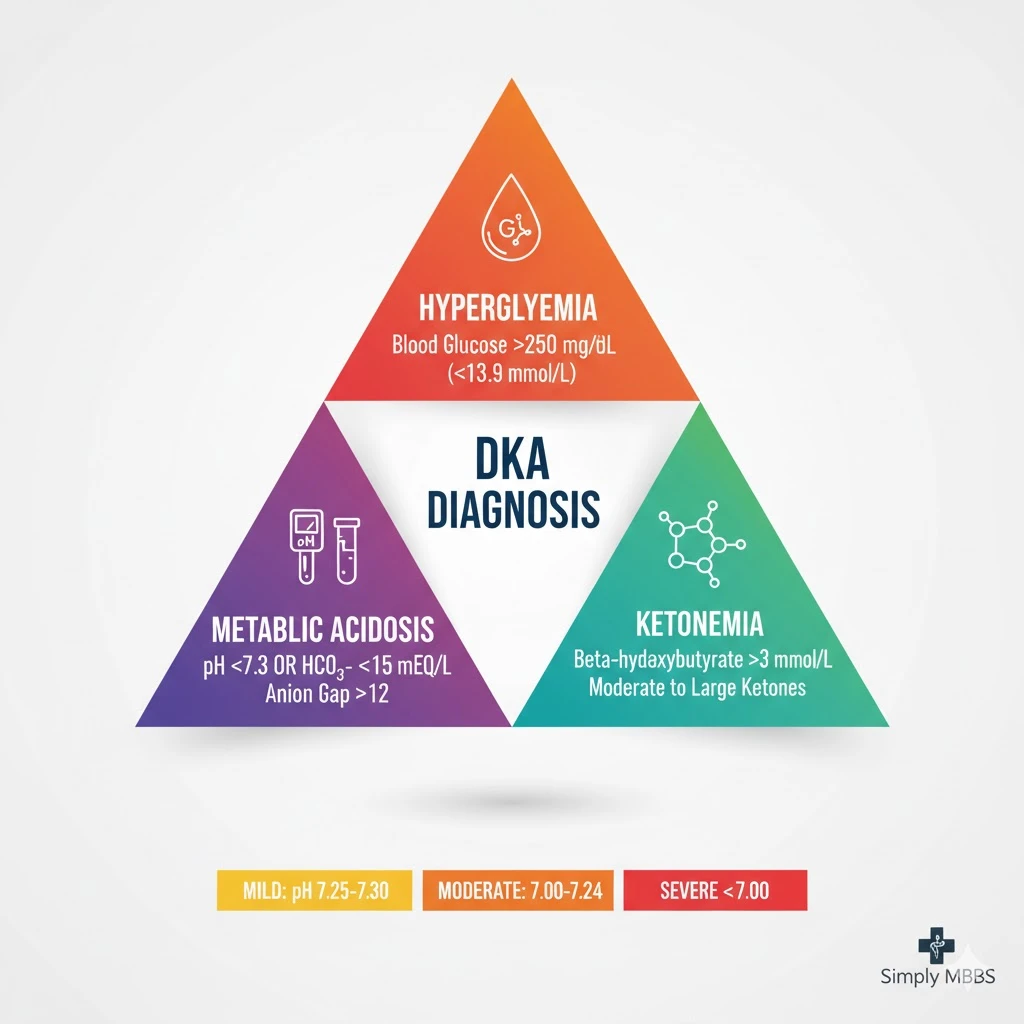

Diabetic Ketoacidosis is defined as a serious metabolic complication of diabetes mellitus characterized by the triad of hyperglycemia (blood glucose >250 mg/dL), anion gap metabolic acidosis (pH <7.3), and ketonemia or ketonuria. This condition results from absolute or relative insulin deficiency combined with elevated counter-regulatory hormones, leading to uncontrolled lipolysis, excessive ketone body production, and severe metabolic derangement.

According to the American Diabetes Association, DKA is diagnosed when all three criteria are present: blood glucose exceeding 250 mg/dL (13.9 mmol/L), arterial pH less than 7.3 or serum bicarbonate less than 15 mEq/L, and the presence of moderate to large serum ketones (beta-hydroxybutyrate >3 mmol/L).

The International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes further categorizes DKA into mild, moderate, and severe based on the degree of acidosis and mental status alterations. This classification system helps clinicians determine appropriate treatment intensity and monitoring requirements.

Why Diabetic Ketoacidosis Matters

Epidemiology and Global Impact

Diabetic Ketoacidosis accounts for approximately 14% of all hospital admissions among diabetic patients and contributes to 16% of diabetes-related deaths worldwide. The condition predominantly affects individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus, though it can occur in type 2 diabetes patients under specific circumstances. The incidence of DKA ranges from 0 to 56 per 1,000 person-years, with significant geographic variation.

In developed countries like the United States, mortality rates from DKA have declined to 0.2-2%, thanks to improved treatment protocols and early recognition. However, in developing countries including parts of India, mortality rates remain concerning at 6-24%, often due to delayed presentation, limited healthcare access, and inadequate treatment facilities.

The financial burden of DKA is substantial, with each hospitalization costing approximately $17,000-26,000 in the United States. In India, while absolute costs are lower, the relative economic impact on families can be devastating. Beyond monetary concerns, DKA causes significant morbidity including cerebral edema (particularly in children), acute kidney injury, and long-term cognitive effects.

For MBBS students and doctors, understanding Diabetic Ketoacidosis is crucial because prompt recognition and appropriate management can dramatically reduce mortality from over 50% (historically) to less than 2% with modern protocols. General public awareness is equally important, as recognizing early warning signs can prevent progression to severe DKA requiring intensive care admission.

Pathophysiology: How Diabetic Ketoacidosis Develops

Insulin Deficiency and Counter-Regulatory Hormones

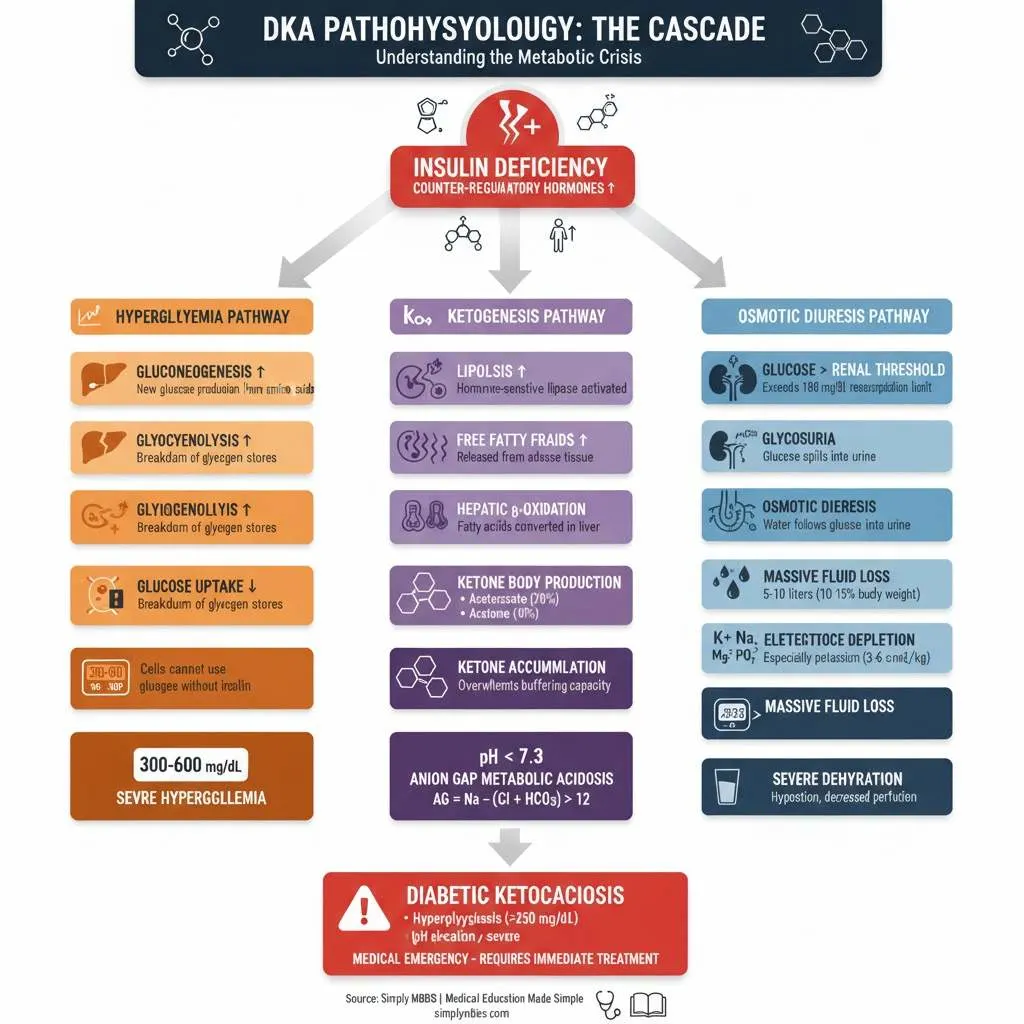

The pathophysiology of Diabetic Ketoacidosis begins with absolute or relative insulin deficiency, which triggers a complex cascade of metabolic derangements. When insulin levels are insufficient, glucose cannot enter cells effectively, leading to cellular starvation despite elevated blood glucose levels. This metabolic crisis prompts the release of counter-regulatory hormones including glucagon, cortisol, catecholamines (epinephrine and norepinephrine), and growth hormone.

These counter-regulatory hormones drive the body into a catabolic state, characterized by three key processes: accelerated glycogenolysis (breakdown of glycogen stores), enhanced gluconeogenesis (creation of new glucose from non-carbohydrate sources like amino acids), and impaired peripheral glucose utilization. The net result is severe hyperglycemia, often exceeding 300-600 mg/dL.

Ketogenesis and Metabolic Acidosis Development

The hallmark feature of DKA is ketone body production through excessive lipolysis. Insulin deficiency and elevated counter-regulatory hormones stimulate hormone-sensitive lipase in adipose tissue, causing rapid breakdown of triglycerides into free fatty acids and glycerol. These free fatty acids are transported to the liver, where they undergo beta-oxidation in mitochondria.

Under normal circumstances, acetyl-CoA produced from fatty acid oxidation enters the citric acid cycle. However, during insulin deficiency, acetyl-CoA accumulates and is diverted to ketone body synthesis. The liver produces three ketone bodies: beta-hydroxybutyrate (the predominant form), acetoacetate, and acetone. Beta-hydroxybutyrate and acetoacetate are strong organic acids that dissociate readily, releasing hydrogen ions and causing anion gap metabolic acidosis.

As serum ketones accumulate beyond the body’s buffering capacity (typically >3 mmol/L), blood pH drops below 7.3, triggering the acidotic state characteristic of DKA. The anion gap (calculated as Na+ – [Cl- + HCO3-]) typically exceeds 12-14 mEq/L, reflecting the presence of unmeasured anions (ketone bodies).

Osmotic Diuresis and Electrolyte Imbalances

Severe hyperglycemia exceeds the renal threshold for glucose reabsorption (approximately 180 mg/dL), causing glycosuria. Glucose in the renal tubules creates an osmotic gradient that prevents water reabsorption, resulting in profound osmotic diuresis. Patients may lose 5-10 liters of fluid (representing 10-15% of total body weight), leading to severe dehydration, hypotension, and decreased renal perfusion.

The osmotic diuresis also causes massive electrolyte losses. Despite total body potassium depletion (deficits of 3-6 mEq/kg), initial serum potassium levels may appear normal or even elevated due to extracellular shifts caused by acidosis and insulin deficiency. Sodium, chloride, magnesium, and phosphate are similarly depleted through urinary losses. The corrected sodium in DKA calculation (measured sodium + 1.6 × [(glucose – 100) / 100]) helps assess true sodium status, as hyperglycemia causes dilutional hyponatremia.

Read More : Acute Myocardial Infarction (MI): ECG Changes, Early Treatment, and Post-MI Care

Precipitating Factors of Diabetic Ketoacidosis

The Five I’s: Common Diabetic Ketoacidosis Triggers

Understanding the precipitating factors of DKA is essential for both prevention and management. Clinicians often use the mnemonic “Five I’s” to remember common triggers:

Infection represents the most frequent precipitating factor, accounting for 30-40% of DKA cases. Urinary tract infections and pneumonia are particularly common culprits. Even minor infections can trigger the stress response, elevating counter-regulatory hormones and precipitating metabolic decompensation. Fever, leukocytosis, and inflammatory markers are often present, though absence of these findings does not exclude infection.

Insulin insufficiency due to non-compliance or inadequate dosing accounts for 20-25% of cases, particularly in urban populations with socioeconomic barriers to healthcare access. Patients may intentionally skip insulin doses due to cost concerns, fear of hypoglycemia, or psychiatric comorbidities including eating disorders. First-time presentations of previously undiagnosed diabetes (particularly type 1 diabetes mellitus) also fall into this category.

Infarction (myocardial infarction or stroke) represents vascular events that trigger massive stress responses. The resulting surge in counter-regulatory hormones can precipitate DKA even in previously well-controlled diabetics. Any patient presenting with DKA should have cardiac workup including electrocardiogram and troponin levels.

Indiscretion (dietary or medication) includes circumstances like excessive alcohol consumption, illicit drug use (cocaine, methamphetamine), or initiation of medications that affect glucose metabolism such as corticosteroids, thiazide diuretics, atypical antipsychotics (clozapine, olanzapine), or SGLT-2 inhibitors.

Iatrogenic causes include insulin pump malfunction, discontinuation of insulin during surgical procedures, or medication errors. SGLT-2 inhibitors deserve special mention as they can cause euglycemic DKA (glucose <250 mg/dL), a diagnostically challenging variant.

Special Populations and Risk Factors

Certain populations face elevated DKA risk. Adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes experience recurrent DKA more frequently, often related to psychosocial stressors, eating disorders, or intentional insulin omission for weight control. Pregnancy increases susceptibility due to insulin resistance and lower buffering capacity. Patients from lower socioeconomic backgrounds face higher rates due to medication access issues and delayed healthcare seeking.

Clinical Presentation and Symptoms of Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Early Warning Signs

The clinical presentation of Diabetic Ketoacidosis typically evolves over hours to days, allowing an intervention window if recognized early. Initial symptoms reflect hyperglycemia and include the classic diabetes triad of polyuria (excessive urination), polydipsia (excessive thirst), and polyphagia (excessive hunger despite eating). Patients often report recent unintentional weight loss due to fluid depletion and catabolism of fat and muscle tissues.

As dehydration progresses, patients develop nausea, vomiting, and diffuse abdominal pain that may mimic acute abdomen. The abdominal pain in DKA correlates with the severity of acidosis and typically resolves with treatment. Generalized weakness, fatigue, and muscle cramps reflect electrolyte imbalances and cellular energy depletion.

Advanced Physical Examination Findings

On physical examination, patients with DKA display multiple characteristic signs. Vital signs reveal tachycardia (compensatory response to volume depletion), tachypnea, and potentially hypotension in severe cases. Blood pressure findings help categorize severity—mild DKA patients maintain normal blood pressure, while severe cases show orthostatic hypotension or frank shock.

The respiratory pattern known as Kussmaul breathing (deep, labored, sighing respirations) represents the body’s compensatory attempt to excrete carbon dioxide and partially correct metabolic acidosis. Respiratory rate may reach 20-30 breaths per minute with pronounced chest wall movement. Some clinicians can detect a fruity or acetone odor on the patient’s breath, caused by volatile acetone excretion through the lungs, though this finding is neither sensitive nor specific.

Signs of dehydration include poor skin turgor (skin tenting), dry mucous membranes, sunken eyes, decreased axillary sweating, and delayed capillary refill. Mental status ranges from full alertness in mild cases to confusion, lethargy, or coma in severe DKA. Altered consciousness correlates with plasma osmolality—patients with osmolality exceeding 320-330 mOsm/kg typically show significant cognitive impairment.

Abdominal examination may reveal diffuse tenderness without peritoneal signs. This “pseudoperitonitis” resolves with DKA treatment and should not prompt immediate surgical consultation unless other acute abdominal pathology is strongly suspected. Signs of the precipitating event (fever suggesting infection, chest pain suggesting MI) should be specifically sought.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Diagnosis: A Systematic Approach

DKA Diagnostic Criteria: The Essential Triad

DKA diagnosis requires systematic laboratory evaluation confirming all three components of the diagnostic triad. The DKA diagnostic criteria established by the American Diabetes Association categorize severity into mild, moderate, and severe based on specific thresholds:

Mild DKA:

- Blood glucose >250 mg/dL (>13.9 mmol/L)

- Arterial pH 7.25-7.30

- Serum bicarbonate 15-18 mEq/L

- Anion gap >10 mEq/L

- Positive urine or serum ketones

- Alert mental status

Moderate DKA:

- Blood glucose >250 mg/dL

- Arterial pH 7.00-7.24

- Serum bicarbonate 10-14 mEq/L

- Anion gap >12 mEq/L

- Positive ketones

- Alert or drowsy

Severe DKA:

- Blood glucose >250 mg/dL

- Arterial pH <7.00

- Serum bicarbonate <10 mEq/L

- Anion gap >12 mEq/L

- Positive ketones

- Stupor or coma

Arterial Blood Gas in DKA: Interpretation Guide

Arterial blood gas in DKA analysis reveals high anion gap metabolic acidosis with compensatory respiratory alkalosis. The typical ABG pattern shows:

- pH: <7.3 (acidemia)

- PaCO2: Reduced (20-30 mmHg) due to compensatory hyperventilation

- HCO3-: Markedly reduced (<15 mEq/L)

- PaO2: Usually normal unless concurrent respiratory pathology

The expected PaCO2 can be calculated using Winter’s formula: Expected PaCO2 = (1.5 × HCO3-) + 8 ± 2. If the actual PaCO2 exceeds the expected value, consider concurrent respiratory acidosis. If the actual PaCO2 is lower than expected, a mixed disorder with additional respiratory alkalosis may exist.

Venous blood gas (VBG) serves as an acceptable alternative to arterial sampling for DKA diagnosis and monitoring. Venous pH averages 0.03 units lower than arterial pH, and venous bicarbonate closely approximates arterial values. VBG reduces patient discomfort and is particularly useful for serial monitoring during treatment.

Corrected Sodium in DKA: Clinical Significance

The corrected sodium in DKA calculation is crucial for assessing true sodium status and guiding fluid therapy. Hyperglycemia causes water to shift from the intracellular to extracellular compartment, diluting serum sodium. The correction formula is:

Corrected Sodium = Measured Sodium + 1.6 × [(Glucose – 100) / 100]

For glucose values in mmol/L, use:

Corrected Sodium = Measured Sodium + 0.3 × (Glucose – 5.5)

Failure of corrected sodium to rise appropriately during treatment (as glucose decreases) indicates inadequate sodium replacement or excessive free water administration, and represents a risk factor for cerebral edema in DKA, particularly in pediatric patients.

Laboratory Investigations: Complete Workup

A comprehensive metabolic panel for DKA includes:

Essential Tests:

- Blood glucose (often 300-800 mg/dL)

- Serum ketones (beta-hydroxybutyrate >3 mmol/L preferred over urine ketones)

- Arterial or venous blood gas

- Serum electrolytes (sodium, potassium, chloride, bicarbonate)

- Anion gap calculation: (Na+ – [Cl- + HCO3-])

- Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine (assess renal function)

- Complete blood count (leukocytosis common even without infection)

Additional Tests:

- Urine ketones and urinalysis

- Serum osmolality: 2 × Na+ + (glucose/18) + (BUN/2.8)

- Phosphate, magnesium, calcium

- Hemoglobin A1C (reflects 3-month glucose control)

- Lipase (may be elevated without true pancreatitis)

- Lactate (exclude concurrent lactic acidosis)

- Electrocardiogram (identify ischemia, electrolyte abnormalities)

- Cultures (blood, urine, sputum if infection suspected)

- Pregnancy test in women of childbearing age

Read More : Approach to Unconscious Patient: Causes, Diagnosis, and Emergency Management

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Management: Evidence-Based Protocol

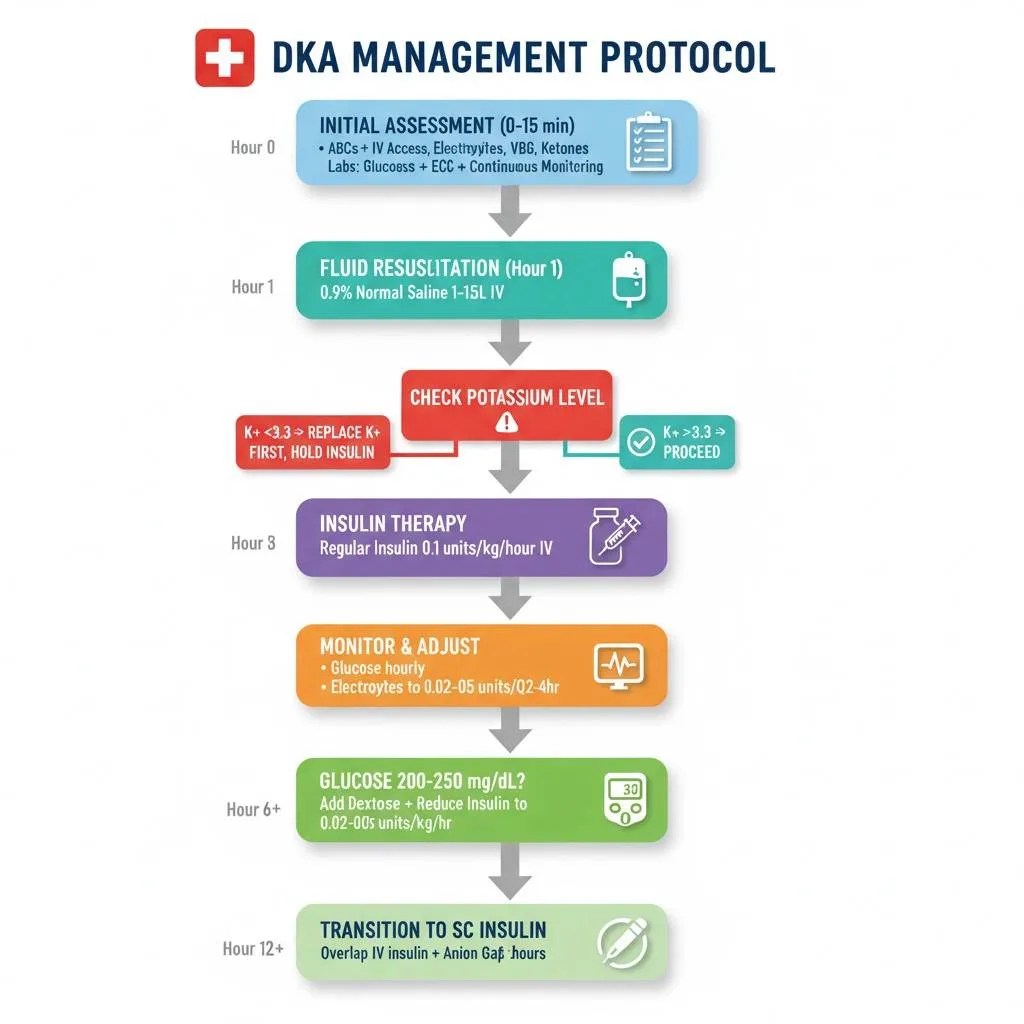

Initial Assessment and Stabilization

Successful diabetic ketoacidosis management requires rapid assessment, aggressive treatment, and meticulous monitoring. The treatment approach follows the ABCDE resuscitation protocol—Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability (neurological assessment), and Exposure. Patients with altered mental status, severe acidosis (pH <7.0), or respiratory fatigue may require airway protection, though intubation in DKA carries significant risks and should be avoided when possible.

Establish large-bore intravenous access (two sites preferred) immediately. Begin continuous cardiac monitoring and pulse oximetry. Measure baseline vital signs, weight (if possible), and perform a focused physical examination. The DKA management protocol begins with simultaneous fluid resuscitation and laboratory evaluation, followed by insulin therapy once potassium levels are confirmed safe.

Initial Fluid Resuscitation in Diabetic Ketoacidosis: The Foundation

Initial fluid resuscitation in DKA is the cornerstone of treatment, addressing severe volume depletion (typical deficit 5-10 liters). Aggressive hydration improves tissue perfusion, decreases counter-regulatory hormone levels, reduces hyperglycemia through increased renal glucose excretion, and helps clear ketones.

Hour 1 (Resuscitation Phase):

- Administer 0.9% normal saline 15-20 mL/kg/hour (typically 1-1.5 liters in adults)

- In hemodynamically unstable patients, give initial bolus of 1 liter over 10-15 minutes

- Reassess volume status after first hour

Hours 2-24 (Maintenance Phase):

- If corrected sodium is normal or low: Continue 0.9% normal saline at 250-500 mL/hour (4-14 mL/kg/hour)

- If corrected sodium is elevated: Switch to 0.45% half-normal saline at similar rate

- Adjust rate based on hemodynamics, urine output, and hydration status

When Glucose Reaches 200-250 mg/dL:

- Add dextrose to intravenous fluids (D5W in 0.45% saline or D10W in water)

- Continue insulin infusion despite euglycemia to clear ketones

- Maintain glucose at 150-200 mg/dL until DKA resolution

Recent studies comparing aggressive (1 liter/hour) versus moderate (500 mL/hour) fluid resuscitation show similar outcomes in uncomplicated cases, though critically ill patients benefit from more aggressive initial hydration. The traditional concern about cerebral edema from rapid fluid administration has not been consistently demonstrated in recent literature, though vigilance remains appropriate, particularly in pediatric patients.

Insulin Infusion Rate in DKA: Dosing and Adjustment

Insulin infusion rate in DKA follows a standardized low-dose continuous infusion protocol that has replaced historical high-dose regimens. Regular insulin (short-acting) administered intravenously is the gold standard.

Insulin Initiation:

- No initial bolus is required—begin continuous infusion at 0.1-0.14 units/kg/hour

- Alternative: Give 0.1 units/kg IV bolus, then infuse at 0.1 units/kg/hour

- For 70 kg patient: Start infusion at 7-10 units/hour

- Standard preparation: 100 units regular insulin in 100 mL normal saline (1 unit/mL)

Critical: Never start insulin until potassium is >3.3 mEq/L to avoid potentially fatal hypokalemia and cardiac arrhythmias.

Insulin Adjustment During Treatment:

- Expected glucose decrease: 50-75 mg/dL per hour

- If glucose drops <50 mg/dL in first hour: Continue current rate (often indicates severe dehydration resolving)

- If glucose does not drop by ≥10% in first hour: Give 0.1 units/kg bolus and continue infusion

- When glucose reaches 200-250 mg/dL: Reduce insulin to 0.02-0.05 units/kg/hour (typically 2-5 units/hour)

- Add dextrose-containing fluids at this point

- Continue insulin until DKA resolution, NOT just until euglycemia

Resolution Criteria:

- Glucose <200 mg/dL AND

- Two of the following: pH >7.3, bicarbonate ≥15 mEq/L, anion gap ≤12 mEq/L

Potassium Replacement in DKA: Preventing Dangerous Hypokalemia

Potassium replacement in DKA is critical because total body potassium is depleted by 3-6 mEq/kg despite normal or elevated initial serum levels. Insulin therapy drives potassium intracellularly, potentially causing life-threatening hypokalemia.

Potassium Management Protocol:

If K+ <3.3 mEq/L: HOLD INSULIN. Give potassium chloride 20-30 mEq/hour until K+ >3.3 mEq/L, then start insulin.

3.3-5.0 mEq/L: Add 20-30 mEq potassium to each liter of IV fluid (typically as KCl)

5.0-5.5 mEq/L: Add 10-20 mEq potassium to each liter of IV fluid

>5.5 mEq/L: Hold potassium supplementation; recheck in 2 hours

Target range during treatment: Maintain serum potassium 4.0-5.0 mEq/L throughout DKA management. Check potassium every 2-4 hours initially, then every 4-6 hours once stable. Hypomagnesemia (common in DKA) impairs potassium repletion; check magnesium and replace if low.

Bicarbonate in DKA—Indications: Controversial Territory

The use of bicarbonate in DKA remains controversial with limited evidence supporting benefit. Most guidelines recommend against routine bicarbonate administration, as it may worsen intracellular acidosis, cause paradoxical CNS acidosis, increase risk of hypokalemia, and potentially increase cerebral edema risk.

Consider Bicarbonate Only If:

- pH <6.9 despite adequate fluid and insulin therapy

- Life-threatening hyperkalemia

- Severe acidosis with cardiovascular instability

If Given:

- Add 100 mmol (2 ampules) sodium bicarbonate to 400 mL sterile water with 20 mEq KCl

- Infuse at 200 mL/hour over 2 hours

- Recheck pH after 2 hours; repeat if pH remains <7.0

- Maximum: Do not exceed pH 7.0 with bicarbonate therapy

Phosphate and Magnesium Replacement

Phosphate levels frequently drop during DKA treatment as insulin drives phosphate intracellularly. Severe hypophosphatemia (<1.0 mg/dL) can cause respiratory muscle weakness, rhabdomyolysis, and hemolytic anemia, though routine phosphate replacement has not shown clinical benefit in most studies.

Phosphate Replacement (if indicated):

- Give only if serum phosphate <1.0 mg/dL and patient symptomatic

- Use potassium phosphate 20-30 mEq per liter IV fluid

- Monitor calcium (phosphate administration can cause hypocalcemia)

Magnesium depletion is common and may impair potassium repletion. Replace magnesium if levels <1.8 mg/dL using magnesium sulfate 1-2 grams IV over 2 hours.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Management Protocol: Step-by-Step

This DKA management protocol MBBS students can follow provides a systematic approach to managing Diabetic Ketoacidosis from presentation through resolution.

Step 1: Initial Assessment (0-15 minutes)

- Assess airway, breathing, circulation

- Establish two large-bore IV lines

- Obtain stat labs: glucose, electrolytes, VBG/ABG, CBC, renal function, ketones

- Start continuous cardiac monitoring

- Obtain ECG

- Insert urinary catheter for strict I/O monitoring

- Search for precipitating cause

2: Immediate Fluid Resuscitation (0-60 minutes)

- Give 0.9% normal saline 1-1.5 liters IV over 1 hour

- Reassess volume status

- WAIT for potassium result before starting insulin

3: Insulin Therapy (After K+ Known)

- If K+ >3.3 mEq/L: Start regular insulin 0.1 units/kg/hour IV

- If K+ <3.3 mEq/L: Hold insulin, give potassium replacement first

4: Electrolyte Management (Ongoing)

- Add potassium to IV fluids based on serum levels

- Check electrolytes, glucose, VBG every 2-4 hours initially

- Replace magnesium if low

5: Monitoring Phase

- Hourly glucose monitoring (target decrease 50-75 mg/dL/hour)

- When glucose reaches 200-250 mg/dL: Add dextrose to fluids, reduce insulin rate

- Continue insulin until DKA resolves (pH >7.3, HCO3 ≥15, anion gap ≤12)

6: Transition to Subcutaneous Insulin

- When DKA resolved and patient tolerating oral intake

- Give long-acting insulin (glargine/detemir) or first dose regular insulin SC

- Continue IV insulin for 1-2 hours after first SC dose (overlap prevents rebound)

- Calculate total daily insulin: 0.5-0.8 units/kg/day divided as basal (50%) and bolus (50%)

7: Identify and Treat Precipitating Cause

- Start antibiotics if infection identified

- Address medication non-compliance with education and social work

- Optimize long-term diabetes management

Complications of Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Cerebral Edema in DKA: Most Feared Complication

Cerebral edema in DKA represents the most feared complication, occurring in 0.5-1% of pediatric DKA cases but rarely in adults. Mortality reaches 20-40% among affected patients, with 20-35% of survivors experiencing permanent neurological sequelae. Recognition and immediate treatment are critical.

Risk Factors:

- Age <5 years

- New-onset diabetes

- Longer duration of symptoms (>24 hours)

- Severe acidosis at presentation (pH <7.1)

- Elevated blood urea nitrogen

- Low PaCO2 at presentation

- Failure of corrected sodium to rise during treatment

- Aggressive fluid resuscitation (though this remains debated)

- Bicarbonate administration

Clinical Features:

- Headache

- Altered mental status or decreased level of consciousness

- Vomiting

- Incontinence

- Bradycardia (late finding)

- Hypertension (late finding)

- Pupillary changes

- Respiratory arrest

Management:

- Immediate treatment is essential—do not wait for CT confirmation

- Reduce IV fluid rate by 25-50%

- Give mannitol 0.5-1.0 g/kg IV over 15-20 minutes (first-line)

- Alternative: 3% hypertonic saline 2.5-5 mL/kg over 30 minutes

- Elevate head of bed 30 degrees

- Intubate if necessary (avoid hyperventilation)

- Arrange ICU transfer

- Obtain head CT when patient stable (to exclude hemorrhage, but edema may not be visible early)

Hypoglycemia During DKA Treatment: Common Iatrogenic Complication

The treatment occurs in 5-25% of cases, making it the most common treatment-related complication. Hypoglycemia results from overly aggressive insulin therapy, inadequate glucose supplementation after reaching target range, or failure to reduce insulin infusion rates appropriately.

Prevention Strategies:

- Monitor glucose hourly during acute phase

- When glucose reaches 200-250 mg/dL, add dextrose to IV fluids

- Reduce insulin infusion to 0.02-0.05 units/kg/hour at glucose threshold

- Continue insulin at reduced rate (do not stop) to clear ketones

- Maintain glucose 150-200 mg/dL during remainder of treatment

Treatment if Hypoglycemia Occurs:

- Give 25-50 mL dextrose 50% IV bolus (D50W)

- Recheck glucose in 15 minutes

- Adjust insulin infusion rate

- Increase dextrose concentration in maintenance fluids

Other Significant Complications

Hypokalemia and Cardiac Arrhythmias: Severe hypokalemia (<2.5 mEq/L) causes cardiac arrhythmias including ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and cardiac arrest. ECG shows flattened T waves, U waves, and ST depression. Prevention through vigilant potassium monitoring and replacement is essential.

Hyperchloremic Non-Anion Gap Metabolic Acidosis: Develops during DKA recovery as ketones are cleared and chloride from normal saline accumulates. This is a normal transition and does not require specific treatment beyond continuing hydration and insulin. The anion gap closes but pH may temporarily remain low due to hyperchloremia.

Acute Kidney Injury: Pre-renal azotemia from severe volume depletion is common. Most cases resolve with adequate fluid resuscitation. Rare cases progress to acute tubular necrosis requiring temporary dialysis.

Thrombotic Complications: DKA creates a hypercoagulable state with elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines and pro-coagulant factors. Deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and arterial thromboses can occur. Consider thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized patients.

Mucormycosis: Rare but severe fungal infection (Rhizopus species) affecting immunocompromised patients with DKA. Presents with sinusitis, orbital cellulitis, or pulmonary infiltrates. Requires aggressive surgical debridement and antifungal therapy.

DKA vs HHS: Understanding the Differences

Many MBBS students struggle to differentiate Diabetic Ketoacidosis from Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS), another serious diabetic emergency. Understanding DKA vs HHS distinctions is crucial for appropriate management.

| Feature | DKA | HHS |

|---|---|---|

| Primary diabetes type | Type 1 diabetes | Type 2 diabetes |

| Blood glucose | 250-600 mg/dL | 600-1200 mg/dL (often >800) |

| pH | <7.3 | >7.3 (typically >7.35) |

| Serum bicarbonate | <15 mEq/L | >15 mEq/L |

| Ketones | Strongly positive (+++++) | Absent or minimal (±) |

| Anion gap | High (>12) | Normal or mildly elevated |

| Osmolality | 300-320 mOsm/kg | 320-380 mOsm/kg (often >350) |

| Mental status | Alert to stupor | Confusion to coma common |

| Onset | Hours to days (rapid) | Days to weeks (gradual) |

| Dehydration severity | Moderate (5-8 L deficit) | Severe (8-12 L deficit) |

| Mortality | 0.2-2% | 5-20% (higher) |

| Insulin present | Little to none | Some insulin present |

| Ketogenesis | Severe | Prevented by residual insulin |

Key Pathophysiologic Difference: In DKA, profound insulin deficiency allows uncontrolled lipolysis and ketogenesis. In HHS, sufficient insulin remains to prevent ketone formation but not enough to control glucose, leading to extreme hyperglycemia and hyperosmolality without significant ketoacidosis.

Management Similarities: Both conditions require aggressive fluid resuscitation, insulin therapy, and electrolyte correction. HHS typically requires more total fluid (average 10-12 liters vs. 5-8 liters) and slower glucose correction to prevent osmotic complications.

Read More : Heart Failure: Classification, Diagnosis & Notes

ABG Interpretation in DKA: Clinical Examples

DKA ABG Interpretation Examples for MBBS Students

Understanding arterial blood gas in DKA interpretation is essential for diagnosis and monitoring. Let’s examine three real-world examples:

Example 1: Classic Severe DKA

- pH: 7.08 (acidemia)

- PaCO2: 18 mmHg (low – respiratory compensation)

- HCO3-: 6 mEq/L (very low)

- PaO2: 98 mmHg (normal)

- Glucose: 520 mg/dL

- Ketones: 5.8 mmol/L

Interpretation: High anion gap metabolic acidosis with appropriate respiratory compensation. Calculate expected PaCO2 using Winter’s formula: (1.5 × 6) + 8 = 17 ± 2 (range 15-19). Actual PaCO2 of 18 mmHg is within expected range, confirming pure metabolic acidosis with compensation. This represents severe DKA requiring ICU admission.

Example 2: Moderate DKA with Treatment Response

- pH: 7.22 (acidemia, improving)

- PaCO2: 25 mmHg (low)

- HCO3-: 11 mEq/L (low, improving)

- Glucose: 285 mg/dL

- Ketones: 3.2 mmol/L

Interpretation: Moderate DKA showing treatment response. Expected PaCO2: (1.5 × 11) + 8 = 24.5 ± 2 (range 22.5-26.5). This patient is appropriately compensating and improving with therapy. Continue current management with close monitoring.

Example 3: Resolving DKA with Mixed Disorder

- pH: 7.32 (near normal)

- PaCO2: 32 mmHg (low-normal)

- HCO3-: 16 mEq/L (low)

- Chloride: 112 mEq/L (elevated)

- Glucose: 180 mg/dL

- Ketones: 1.2 mmol/L

- Anion gap: 8 mEq/L (normal)

Interpretation: Resolving DKA with transition to hyperchloremic non-anion gap acidosis. The anion gap has normalized as ketones cleared, but pH remains slightly low due to elevated chloride from normal saline administration. This is expected during recovery and requires no specific intervention beyond continued hydration.

Case Presentation: Real Patient Example

Diabetic Ketoacidosis Case Presentation for MBBS Clinical Learning

Patient Details: A 22-year-old female college student presents to the emergency department with 2-day history of nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and progressive confusion.

History of Presenting Illness: The patient reports “feeling unwell” for 5 days with fever, sore throat, and cough. Despite poor oral intake, she continued her usual insulin regimen (insulin glargine 20 units daily, insulin aspart with meals). Over the past 48 hours, she developed persistent vomiting, could not tolerate any food or liquids, and therefore stopped taking insulin “to avoid low blood sugar.” Her roommate reports increasing lethargy and confusion over the past 12 hours.

Past Medical History:

- Type 1 diabetes diagnosed age 14

- Generally good control (recent HbA1c 7.2%)

- No previous DKA episodes

- No other medical problems

Physical Examination:

- Vital Signs: BP 95/60 mmHg, HR 118 bpm, RR 28/min, Temperature 38.2°C (100.8°F), SpO2 98% room air

- General: Lethargic but arousable, appears dehydrated

- HEENT: Dry mucous membranes, sunken eyes, pharyngeal erythema

- Cardiovascular: Tachycardic, regular rhythm, no murmurs

- Respiratory: Deep, labored breathing (Kussmaul pattern), clear lung fields, fruity breath odor

- Abdomen: Diffuse tenderness without guarding or rebound

- Neurological: Confused to time and place, no focal deficits

- Skin: Poor turgor, cool extremities

Laboratory Results:

- Glucose: 485 mg/dL

- Sodium: 132 mEq/L (corrected: 138 mEq/L)

- Potassium: 5.2 mEq/L

- Chloride: 98 mEq/L

- Bicarbonate: 9 mEq/L

- BUN: 32 mg/dL

- Creatinine: 1.4 mg/dL

- Anion gap: 25 mEq/L

- VBG: pH 7.12, PCO2 22 mmHg, HCO3 8 mEq/L

- Beta-hydroxybutyrate: 6.2 mmol/L

- WBC: 18,500/µL (left shift)

- Urinalysis: 3+ ketones, 4+ glucose

Diagnosis: Severe Diabetic Ketoacidosis precipitated by upper respiratory infection and insulin non-compliance.

Management Implemented:

- Hour 0-1: 0.9% normal saline 1.5 liters IV, blood cultures, rapid strep test (positive)

- Hour 1: Started regular insulin infusion 7 units/hour (0.1 units/kg/hour), added 20 mEq KCl to next liter NS

- Hour 2-4: Continued fluid resuscitation 250 mL/hour with potassium supplementation, started amoxicillin for streptococcal pharyngitis

- Hour 6: Glucose decreased to 220 mg/dL, switched to D5 0.45% NS, reduced insulin to 3 units/hour

- Hour 12: pH 7.32, HCO3 16 mEq/L, anion gap 12 mEq/L—DKA resolved

- Hour 14: Patient tolerating oral intake, gave subcutaneous insulin, continued IV insulin overlap 2 hours

- Day 2: Transitioned to home insulin regimen with adjustments, patient education reinforced

Learning Points:

- Upper respiratory infection precipitated DKA through stress response

- Patient error: Stopping insulin during illness with poor oral intake

- Proper sick day management could have prevented this admission

- Treatment followed standard protocol with good outcome

- Patient education critical to prevent recurrence

- Common Mistakes to Avoid in DKA Management

MBBS students and junior doctors frequently make these errors when managing Diabetic Ketoacidosis. Learn from others’ mistakes:

Mistake 1: Starting insulin before checking potassium. Insulin drives potassium intracellularly, potentially causing fatal cardiac arrhythmias if baseline potassium is already low. Always wait for potassium result.

Mistake 2: Stopping insulin when glucose normalizes. Glucose corrects faster than ketoacidosis clears. Continue insulin at reduced rate with dextrose supplementation until pH >7.3 and anion gap closes.

Mistake 3: Using sliding scale insulin instead of continuous infusion. Subcutaneous insulin absorption is erratic in dehydrated patients. IV regular insulin infusion is the standard of care for acute DKA.

Mistake 4: Inadequate fluid resuscitation. Aggressive hydration is the foundation of DKA treatment. Under-resuscitation delays improvement and increases complications.

Mistake 5: Routine bicarbonate administration. Most patients do not benefit from bicarbonate and may experience harm. Reserve for pH <6.9 with severe symptoms only.

Mistake 6: Ignoring the precipitating cause. Always search for and treat the trigger (infection, medication non-compliance, etc.). Failure to address the cause increases recurrence risk.

Mistake 7: Not overlapping IV and subcutaneous insulin. When transitioning to subcutaneous insulin, continue IV infusion for 1-2 hours after first SC dose to prevent rebound DKA.

Mistake 8: Failure to educate patients. Prevention of future episodes requires comprehensive diabetes education, sick-day management teaching, and addressing barriers to medication adherence.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Diabetic Ketoacidosis

Q : Can type 2 diabetes patients develop DKA?

A : Yes, though Diabetic Ketoacidosis primarily affects type 1 diabetes patients, type 2 diabetes individuals can develop DKA under severe stress, with SGLT-2 inhibitor use, or in ketosis-prone diabetes variants. Type 2 DKA often occurs with severe infections, cardiac events, or prolonged hyperglycemia.

Q : What is euglycemic DKA?

A : Euglycemic DKA refers to diabetic ketoacidosis with blood glucose <250 mg/dL. This occurs with SGLT-2 inhibitor use, alcohol consumption, pregnancy, or prolonged fasting while continuing insulin. Diagnosis requires high suspicion as glucose levels may not trigger typical DKA concerns.

Q : How long does DKA treatment typically take?

A : Resolution of DKA typically occurs within 12-24 hours of initiating treatment. However, total hospitalization averages 3-5 days to ensure stability, address precipitating factors, and transition to outpatient management safely.

Q : Is DKA contagious?

A : No, Diabetic Ketoacidosis itself is not contagious. However, infections that trigger DKA (like flu or strep throat) may be transmissible. The metabolic crisis of DKA results from insulin deficiency, not infection.

Q : Can DKA cause permanent damage?

A : Most patients recover fully from DKA without permanent effects. However, cerebral edema in DKA can cause lasting neurological damage or death. Repeated DKA episodes may contribute to long-term complications of diabetes including kidney disease and neuropathy.

Q : What are sick day rules to prevent DKA?

A : Sick day rules include: (1) Never skip insulin doses—may need more insulin during illness, (2) Check glucose every 2-4 hours, (3) Check urine or blood ketones if glucose >250 mg/dL, (4) Maintain hydration, (5) Seek medical attention if ketones are moderate/large or vomiting prevents oral intake.

Q : Is hospitalization always required for DKA?

A : Mild DKA in select patients may be managed in emergency department observation units with 12-24 hour monitoring and discharge. However, moderate to severe DKA, pediatric cases, elderly patients, or those with complications require full hospital admission, often to intensive care units.

Exam Preparation: Questions and Answers for MBBS Students

Short Answer Questions (5 marks each)

Question 1: Write a short note on the pathophysiology of Diabetic Ketoacidosis. (5 marks)

Model Answer:

Diabetic Ketoacidosis pathophysiology involves absolute or relative insulin deficiency combined with excess counter-regulatory hormones (glucagon, cortisol, catecholamines, growth hormone). This leads to:

- Hyperglycemia: Increased gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis, decreased peripheral glucose utilization (2 marks)

- Ketogenesis: Insulin deficiency triggers lipolysis in adipose tissue, releasing free fatty acids. Hepatic beta-oxidation converts fatty acids to ketone bodies (beta-hydroxybutyrate, acetoacetate, acetone), causing anion gap metabolic acidosis (2 marks)

- Dehydration: Osmotic diuresis from glycosuria causes fluid losses of 5-10 liters with electrolyte depletion, particularly potassium (1 mark)

Question 2: List the diagnostic criteria for Diabetic Ketoacidosis according to ADA guidelines. (5 marks)

Model Answer:

DKA diagnostic criteria require presence of:

- Hyperglycemia: Blood glucose >250 mg/dL (>13.9 mmol/L) (1 mark)

- Metabolic acidosis: Arterial pH <7.3 OR serum bicarbonate <15 mEq/L (1.5 marks)

- Ketonemia or ketonuria: Beta-hydroxybutyrate >3 mmol/L or moderate/large urine ketones (1.5 marks)

- Anion gap >10-12 mEq/L indicating high anion gap metabolic acidosis (1 mark)

Severity classification: Mild (pH 7.25-7.30), Moderate (pH 7.0-7.24), Severe (pH <7.0)

Long Answer Questions (10 marks each)

Question 3: Describe the management protocol of a 25-year-old patient presenting with severe Diabetic Ketoacidosis. (10 marks)

Model Answer:

Initial Assessment (1 mark):

- ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation), IV access, continuous monitoring

- Stat labs: glucose, electrolytes, VBG/ABG, ketones, CBC, renal function

Fluid Therapy (2 marks):

- Hour 1: 0.9% normal saline 15-20 mL/kg (1-1.5 L)

- Maintenance: 250-500 mL/hour based on corrected sodium

- When glucose reaches 200-250 mg/dL: Add dextrose (D5 or D10)

Insulin Therapy (2 marks):

- Wait for potassium >3.3 mEq/L before starting insulin

- Regular insulin 0.1 units/kg/hour IV continuous infusion

- Target glucose decrease 50-75 mg/dL/hour

- Reduce to 0.02-0.05 units/kg/hour when glucose reaches 200-250 mg/dL

Electrolyte Management (2 marks):

- Potassium: Add 20-30 mEq/L to fluids if K+ 3.3-5.0 mEq/L

- Monitor K+ every 2-4 hours

- Replace magnesium if low

Monitoring (1 mark):

- Hourly glucose, electrolytes every 2-4 hours

- VBG every 4-6 hours until resolution

Resolution Criteria (1 mark):

-

Glucose <200 mg/dL AND pH >7.3, HCO3 ≥15, or anion gap ≤12

Transition (1 mark):

- Subcutaneous insulin when patient tolerating oral intake

- Continue IV insulin 1-2 hours after first SC dose

- Address precipitating cause, patient education

DKA Flowchart for Exam (Create Your Own Diagram)

Flowchart Elements to Include:

Patient Presents with Suspected DKA

↓

Initial Assessment: ABCs, IV Access, Labs

↓

Confirm Diagnosis: Glucose >250, pH <7.3, Ketones +

↓

Check Potassium Level

↓

├─ K+ <3.3 → Give K+ Replacement, HOLD Insulin

└─ K+ >3.3 → Proceed to Treatment

↓

Start Fluids (NS 1-1.5L first hour)

↓

Start Insulin (0.1 units/kg/hr)

↓

Monitor: Glucose hourly, Electrolytes Q2-4hr

↓

Glucose 200-250? → Add Dextrose, Reduce Insulin

↓

DKA Resolved? (pH >7.3, AG ≤12)

↓

Transition to SC Insulin

↓

Treat Precipitating Cause

↓

Patient Education → Discharge

Viva Questions and Answers

Q: What is the most important initial step in DKA management?

A: Fluid resuscitation with isotonic saline (0.9% NS) to restore intravascular volume and tissue perfusion.

Q: Why do we calculate corrected sodium in DKA?

A: Hyperglycemia causes water shift from intracellular to extracellular space, diluting sodium. Corrected sodium in DKA reveals true sodium status and guides fluid choice.

Q: When should you add dextrose during DKA treatment?

A: When blood glucose reaches 200-250 mg/dL, add dextrose to IV fluids to prevent hypoglycemia while continuing insulin to clear ketones.

Q: What is the significance of anion gap in DKA?

A: Anion gap metabolic acidosis (AG >12) indicates presence of unmeasured anions (ketone bodies). Narrowing of anion gap during treatment indicates ketone clearance and DKA resolution.

Q: How do you differentiate DKA from HHS?

A: DKA has significant ketosis, acidosis (pH <7.3), moderate hyperglycemia (300-600 mg/dL), while HHS has minimal ketones, mild/no acidosis, extreme hyperglycemia (>600 mg/dL), and higher osmolality.

Last-Minute Revision Checklist about Diabetic Ketoacidosis

✓ Diagnostic Triad: Glucose >250, pH <7.3, Ketones +

✓ Never start insulin if K+ <3.3

**✓ Fluid first (1-1.5L hour 1), then insulin

**✓ Insulin dose: 0.1 units/kg/hour IV

**✓ Add dextrose at glucose 200-250 mg/dL

**✓ Resolution: pH >7.3, HCO3 ≥15, AG ≤12

**✓ Overlap IV/SC insulin by 1-2 hours

**✓ Cerebral edema: Mannitol 0.5-1 g/kg IV

**✓ Common precipitants: Infection, insulin non-compliance

**✓ Don’t give routine bicarbonate unless pH <6.9

Conclusion: Key Takeaways

Diabetic Ketoacidosis represents a medical emergency that demands rapid recognition, systematic assessment, and evidence-based treatment. Throughout this comprehensive guide, we have explored the complex pathophysiology of DKA, from insulin deficiency and counter-regulatory hormone excess to the development of anion gap metabolic acidosis and severe dehydration. Understanding the precipitating factors of DKA—particularly infections and insulin non-compliance—enables both prevention and targeted management approaches.

The cornerstone of diabetic ketoacidosis management rests on three pillars: aggressive fluid resuscitation, continuous insulin infusion, and meticulous electrolyte monitoring. The initial fluid resuscitation in DKA addresses life-threatening volume depletion, while careful insulin infusion rate in DKA (0.1 units/kg/hour) and vigilant potassium replacement in DKA prevent treatment complications. Remember the critical rule: never initiate insulin until potassium exceeds 3.3 mEq/L.

For MBBS students, mastering the DKA management protocol MBBS curriculum requires understanding not just the treatment algorithm, but also the rationale behind each intervention. The DKA diagnostic criteria must be committed to memory, and students should practice arterial blood gas in DKA interpretation with multiple examples. Understanding DKA vs HHS differences helps distinguish these hyperglycemic emergencies in examination scenarios and clinical practice.

The most serious DKA complications—particularly cerebral edema in DKA and hypoglycemia during DKA treatment—require heightened awareness and immediate intervention. Prevention strategies, including patient education on sick-day management and recognition