Every day in hospitals worldwide, medical students and junior doctors face a critical decision: which antibiotic should I prescribe? One wrong choice can lead to treatment failure, adverse drug reactions, or worse—fuel the growing crisis of antimicrobial resistance that claims over 1.27 million lives annually. Mastering antibiotic stewardship: principles, common errors, and safe prescribing for MBBS students isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s a fundamental clinical skill that separates competent physicians from those who inadvertently harm patients through inappropriate antimicrobial use.

Antibiotic stewardship: principles, common errors, and safe prescribing for MBBS students represents a systematic approach to optimizing antimicrobial therapy while minimizing resistance development, adverse effects, and healthcare costs. This comprehensive guide walks you through evidence-based prescribing strategies, common pitfalls to avoid, and practical tools you can use during clinical rotations and beyond. Whether you’re preparing for your final MBBS exams or starting your internship, understanding these core concepts will transform you into a responsible prescriber who balances effective treatment with public health responsibility.

What is Antibiotic Stewardship?

Antibiotic stewardship is the systematic effort to measure, monitor, and improve how antibiotics are prescribed by clinicians and used by patients to optimize treatment outcomes while minimizing unintended consequences such as antimicrobial resistance, adverse drug events, and unnecessary healthcare costs.

WHO and CDC Definition

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines antibiotic stewardship as coordinated interventions designed to improve and measure the appropriate use of antimicrobials by promoting the selection of the optimal antibiotic drug regimen, dose, duration of therapy, and route of administration. The World Health Organization (WHO) complements this definition by emphasizing antimicrobial stewardship as a coherent set of actions that promote the responsible use of antimicrobials to preserve their effectiveness for future generations.

Antimicrobial stewardship programs operate on the fundamental principle that not all infections require antibiotics, and when antibiotics are necessary, healthcare providers must select the most appropriate agent with the narrowest spectrum effective against the suspected or confirmed pathogen. This approach, taught in standard medical textbooks like Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine and Mandell’s Principles of Infectious Diseases, emphasizes diagnostic stewardship—confirming infection before prescribing—and therapeutic stewardship—optimizing antibiotic selection, dosing, route, and duration.

Medical students must understand that antibiotic stewardship differs from simple infection control; it’s a proactive, interdisciplinary strategy involving physicians, pharmacists, microbiologists, infection control specialists, and nurses working collaboratively to ensure every antibiotic prescription follows the “4 Ds”: right Drug, right Dose, right Duration, and appropriate De-escalation.

Why Antibiotic Stewardship Matters for Medical Students

Medical students transitioning to clinical practice face immense pressure during ward rounds, emergency department rotations, and overnight calls where rapid antibiotic decisions are expected. Understanding principles of antibiotic stewardship provides the framework for confident, evidence-based prescribing that protects both individual patients and public health.

The Global Antimicrobial Resistance Crisis

Antibiotic resistance & stewardship are inextricably linked. The World Health Organization identified antimicrobial resistance as one of the top 10 global public health threats facing humanity, with projections estimating 10 million annual deaths by 2050 if current trends continue. Every inappropriate antibiotic prescription—whether for viral infections, incorrect dosing, or unnecessarily prolonged duration—contributes to selection pressure favoring resistant bacterial strains.

In the United States, the CDC reports that at least 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occur each year, resulting in more than 35,000 deaths. In India, the burden is even more alarming, with studies showing resistance rates exceeding 70% for common pathogens like Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae to third-generation cephalosporins in many healthcare settings. For MBBS students who will soon write prescriptions independently, understanding these statistics isn’t academic—it’s the reality you’ll navigate daily.

Benefits for Patients and Healthcare Systems

Implementing safe antibiotic prescribing practices delivers measurable benefits across multiple dimensions:

- Improved patient outcomes: Studies demonstrate that appropriate antibiotic therapy reduces mortality in serious infections by 20-30% compared to inappropriate initial therapy

- Reduced adverse drug events: Approximately 20% of hospitalized patients receiving antibiotics experience adverse effects, including Clostridioides difficile infection, allergic reactions, and organ toxicity

- Decreased healthcare costs: Antibiotic stewardship programs save hospitals $200,000-$900,000 annually through reduced drug costs, shorter hospital stays, and fewer complications

- Preserved antibiotic effectiveness: Targeted antibiotic use slows resistance development, maintaining treatment options for future patients

- Enhanced clinical skills: Medical students who learn rational use of antibiotics develop superior diagnostic reasoning and become more thoughtful clinicians

Understanding basic pharmacology principles helps medical students appreciate why stewardship matters—antibiotics aren’t benign drugs to prescribe liberally, but powerful tools requiring judicious use.

Read More : Management of Shock: Types, Clinical Assessment, and Latest Guidelines in Resuscitation

Core Principles of Antibiotic Stewardship

The principles of antibiotic stewardship provide a structured framework that medical students can apply during every patient encounter involving potential infection. These principles, endorsed by the CDC, WHO, and major infectious disease societies, form the foundation of responsible antimicrobial prescribing.

The 7 Core Elements

The CDC’s Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs outline seven essential components that medical students should understand:

1. Leadership Commitment

Hospital administrators and medical leadership must dedicate necessary human, financial, and information technology resources to support antibiotic stewardship initiatives. For students, this means recognizing that your attending physicians and infectious disease consultants are supported by institutional policies designed to optimize prescribing.

2. Accountability

A single physician leader and pharmacist should be appointed to lead stewardship efforts, with clear authority to implement and monitor programs. During rotations, identify these stewardship champions who can provide guidance on complex prescribing decisions.

3. Drug Expertise

Pharmacists with infectious diseases training serve as co-leaders of stewardship programs, providing frontline expertise. Students should actively consult pharmacy colleagues before prescribing unfamiliar antibiotics or managing complex infections.

4. Action

Implementation of evidence-based interventions, including prospective audit and feedback, antibiotic “timeouts” at 48-72 hours, and facility-specific treatment guidelines. Medical students participate in these actions during ward rounds when teams review antibiotic appropriateness.

5. Tracking

Monitoring antibiotic prescribing patterns and resistance trends through antibiograms (explained in detail later). Students should familiarize themselves with their institution’s antibiogram and reference it before empiric prescribing.

6. Reporting

Regular communication of antibiotic use metrics and resistance patterns to prescribers, hospital leadership, and frontline clinicians. Pay attention during morning reports when these data are presented.

7. Education

Continuous training on optimal prescribing practices, resistance patterns, and stewardship principles. As an MBBS student, seek out stewardship lectures, case conferences, and online modules to strengthen your knowledge.

WHO AWaRe Classification System

The World Health Organization developed the AWaRe classification to guide optimal antibiotic selection globally:

| Classification | Description | Examples | Prescribing Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access | First-line antibiotics with low resistance potential | Amoxicillin, Doxycycline, Metronidazole | Should represent ≥60% of total antibiotic consumption |

| Watch | Broader-spectrum agents with higher resistance risk | Third-generation cephalosporins, Quinolones, Macrolides | Reserve for specific indications; require justification |

| Reserve | Last-resort antibiotics for multidrug-resistant organisms | Colistin, Linezolid, Carbapenems | Use only when all alternatives have failed |

How Antibiotic Resistance Develops: Pathophysiology Explained

Understanding the molecular and population-level mechanisms behind antibiotic resistance & stewardship helps medical students appreciate why prescribing decisions have consequences beyond individual patient care.

Molecular Mechanisms

Bacteria develop resistance through four primary mechanisms, each representing a survival strategy against antimicrobial pressure:

1. Enzymatic Inactivation

Bacteria produce enzymes that chemically modify or destroy antibiotics. β-lactamases cleave the β-lactam ring in penicillins and cephalosporins, rendering them inactive. Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs) have evolved to inactivate even advanced cephalosporins, while carbapenemases destroy last-line carbapenems. When students prescribe third-generation cephalosporins for simple infections, they select for ESBL-producing organisms that threaten future treatment options.

2. Target Site Modification

Bacteria alter the molecular structure of antibiotic binding sites, preventing drug attachment. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) produces an altered penicillin-binding protein (PBP2a) with low affinity for β-lactams. Vancomycin-resistant enterococci modify cell wall precursors, eliminating vancomycin’s binding target. These modifications emerge through spontaneous mutations or horizontal gene transfer accelerated by antibiotic exposure.

3. Efflux Pumps

Bacteria express membrane proteins that actively pump antibiotics out of cells faster than they can accumulate to therapeutic concentrations. Multi-drug efflux pumps confer resistance to multiple antibiotic classes simultaneously, creating multidrug-resistant organisms that challenge even experienced infectious disease specialists.

4. Permeability Reduction

Gram-negative bacteria decrease outer membrane permeability by down-regulating porin channels, preventing antibiotic entry. This mechanism particularly affects β-lactams and fluoroquinolones, contributing to the increasing difficulty treating infections caused by organisms like Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii.

Clinical Implications for Prescribers

The pathophysiology of resistance translates directly into clinical prescribing principles every medical student must internalize:

Selection Pressure: Every antibiotic prescription creates selection pressure favoring resistant bacteria while eliminating susceptible strains. A seven-day course of broad-spectrum antibiotics doesn’t just treat the target infection—it alters the patient’s entire microbiome, potentially eliminating beneficial flora while selecting for resistant pathogens that can persist for months.

Horizontal Gene Transfer: Resistance genes spread between bacteria through plasmids, transposons, and bacteriophages. When you prescribe third-generation cephalosporins for a simple urinary tract infection, you may select for ESBL genes that transfer to neighboring E. coli strains, creating resistance that persists long after the antibiotic course ends.

Collateral Damage: Antibiotics exert selective pressure not only on target pathogens but on commensal bacteria throughout the body. This “collateral damage” disrupts protective microbiota in the gut, respiratory tract, and skin, increasing susceptibility to secondary infections like C. difficile colitis and invasive candidiasis.

For MBBS students, these mechanisms underscore a fundamental principle: antibiotic prescribing is never a neutral act. Every prescription represents a balance between immediate therapeutic benefit and long-term ecological consequences requiring careful consideration.

Read More : Acute Kidney Injury (AKI): Clinical Classification, Urine Indices, and Management

Safe Antibiotic Prescribing: The Complete Framework

Safe antibiotic prescribing requires systematic evaluation at every step, from initial assessment through treatment completion. This framework transforms theoretical stewardship principles into actionable clinical practice suitable for medical students during clinical rotations.

Pre-prescription Assessment Checklist

Before writing any antibiotic prescription, complete this systematic assessment:

Confirm Infection Presence

- Does the patient have objective evidence of infection (fever, elevated inflammatory markers, positive cultures)?

- Could symptoms represent non-infectious conditions (autoimmune disease, malignancy, drug fever)?

- Have appropriate cultures been obtained before starting empiric therapy?

Assess Allergy History

- Document specific antibiotic allergies and reaction types (anaphylaxis vs. mild rash)

- Distinguish true allergies from side effects (nausea is not penicillin allergy)

- Note cross-reactivity risks (10% cross-reactivity between penicillins and cephalosporins)

Evaluate Patient Factors

- Age (pediatric dosing differs significantly; elderly patients have altered pharmacokinetics)

- Weight (many antibiotics require weight-based dosing)

- Renal function (most antibiotics need dose adjustment in kidney disease)

- Hepatic function (some antibiotics require dose modification in liver disease)

- Pregnancy/lactation status (many antibiotics are contraindicated)

- Immune status (immunocompromised patients may need broader coverage)

Consider Drug Interactions

- Warfarin interactions with multiple antibiotics

- QT prolongation risk with macrolides and fluoroquinolones

- Reduced oral contraceptive efficacy with rifampin

Review Previous Antibiotic Exposure

- Has the patient received antibiotics in the past 3 months? (Increases resistance risk)

- Did previous courses fail? (Suggests resistant organism)

This systematic approach, taught in clinical rotation preparation courses, ensures students don’t miss critical safety considerations before prescribing.

Choosing the Right Antibiotic: Step-by-Step Guide

The rational use of antibiotics follows a logical sequence that medical students should memorize and apply consistently:

Step 1: Identify the Infection Site

Different anatomical sites have predictable pathogen profiles. Urinary tract infections typically involve E. coli, community-acquired pneumonia commonly involves Streptococcus pneumoniae, and skin/soft tissue infections usually involve Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes.

Step 2: Determine Likely Pathogens

Based on infection site, patient risk factors, and epidemiological patterns, create a short list of probable causative organisms. Consider:

- Community-acquired vs. healthcare-associated infection

- Recent antibiotic exposure

- Recent hospitalization or nursing home residence

- Presence of indwelling devices (catheters, prosthetic joints)

- International travel history

Step 3: Consult the Local Antibiogram

Review your institution’s antibiogram to determine local susceptibility patterns for suspected organisms (see detailed antibiogram guide below).

Step 4: Select Narrowest-Spectrum Effective Agent

Choose the antibiotic with the narrowest spectrum that covers likely pathogens based on antibiogram data. Avoid reflexively reaching for broad-spectrum agents like piperacillin-tazobactam or carbapenems unless clinical severity or resistance risk justifies their use.

Step 5: Determine Optimal Dose and Route

- Serious infections require intravenous therapy initially

- Calculate weight-based dosing for aminoglycosides and vancomycin

- Adjust doses for renal/hepatic impairment

- Ensure adequate tissue penetration (bone infections need prolonged high-dose therapy)

Step 6: Plan Duration and De-escalation

Determine evidence-based treatment duration at the time of prescribing, not as an afterthought. Plan for antibiotic “timeout” at 48-72 hours to review culture results and patient response.

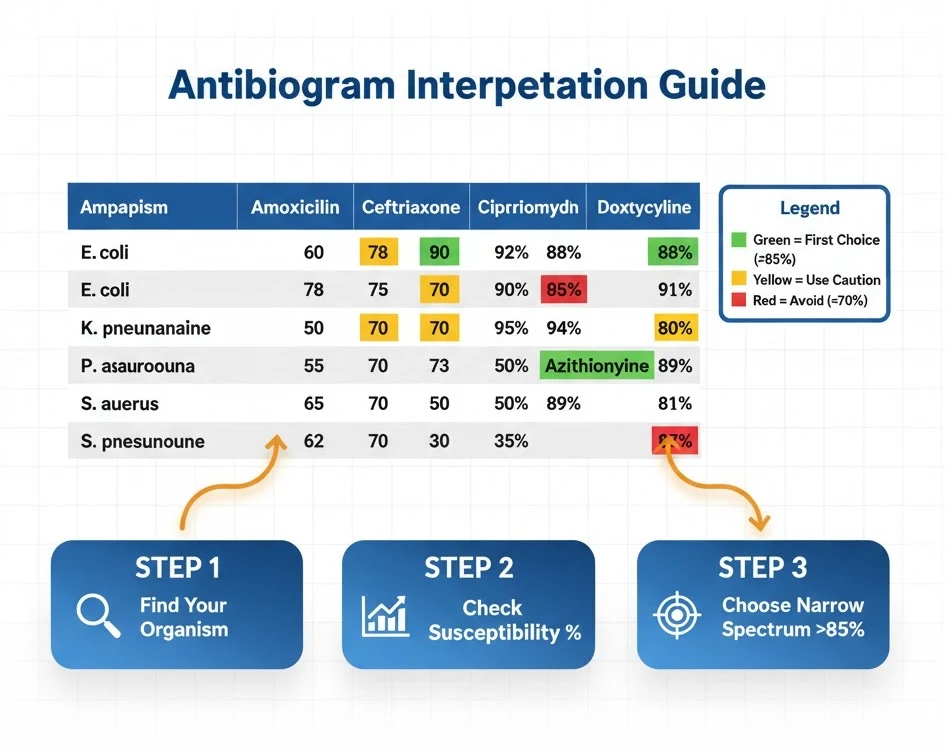

How to Read an Antibiogram for Beginners

Antibiogram DSM represents one of the most practical tools for safe antibiotic prescribing, yet many medical students find these tables intimidating initially. An antibiogram displays cumulative antimicrobial susceptibility data for bacterial isolates in a specific healthcare facility over a defined period, typically one year.

Basic Antibiogram Structure:

- Rows = Bacterial organisms (e.g., E. coli, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa)

- Columns = Antibiotic agents (e.g., ampicillin, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin)

- Cell Values = Percentage of isolates susceptible to that antibiotic

Step-by-Step Interpretation Guide:

Step 1: Identify your suspected organism in the left column. For example, if treating uncomplicated cystitis, locate Escherichia coli in the urinary isolates section.

Step 2: Scan across the row to find antibiotic options. Each percentage represents the proportion of E. coli isolates that tested susceptible to that antibiotic during the past year.

Step 3: Interpret percentages correctly:

- ≥85% susceptibility = Generally appropriate for empiric therapy

- 70-84% susceptibility = Use with caution; consider risk factors for resistance

- <70% susceptibility = Avoid for empiric therapy; reserve for culture-directed treatment

Step 4: Select the narrowest-spectrum agent with ≥85% susceptibility. For uncomplicated UTI, if nitrofurantoin shows 92% susceptibility while ciprofloxacin shows 78%, choose nitrofurantoin to preserve fluoroquinolone effectiveness.

Step 5: Note minimum isolate requirements. Antibiograms only include organisms with ≥30 isolates to ensure statistical validity. Uncommon pathogens may not appear, requiring alternative reference sources.

Common Antibiogram Pitfalls:

- Duplication bias: Antibiograms should exclude duplicate isolates from the same patient, but methodology varies

- Population differences: Hospital antibiograms reflect inpatient resistance patterns that may overestimate resistance in outpatient settings

- Site-specific resistance: Urinary isolates often show different susceptibility than respiratory or blood isolates

- Outdated data: Annual antibiograms may lag current resistance trends during outbreak periods

Medical students should memorize the location of their institution’s current antibiogram and reference it before every empiric antibiotic prescription. Many hospitals provide pocket-sized antibiogram cards or mobile apps—obtain these during your first day of clinical rotations.

When to De-escalate Antibiotics in Sepsis

When to de-escalate antibiotics in sepsis represents one of the most clinically challenging decisions medical students will face during critical care rotations. De-escalation involves transitioning from empiric broad-spectrum antimicrobial therapy to narrower-spectrum targeted therapy based on microbiological data and clinical response.

De-escalation Criteria and Timeline

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines advocate for antibiotic administration within 1 hour for septic shock and within 3 hours for sepsis without shock. However, this early empiric therapy—often involving multiple broad-spectrum agents—must be reassessed systematically to avoid prolonged unnecessary antibiotic exposure.

48-72 Hour Antibiotic Timeout Protocol:

At 48-72 hours after initiating empiric therapy, conduct a structured review:

Microbiological Assessment:

- Are culture results available?

- Has a causative organism been identified?

- What is the organism’s susceptibility profile?

- Can broad-spectrum coverage be narrowed based on susceptibilities?

Clinical Assessment:

- Has the patient achieved clinical stability? (See stability criteria below)

- Are inflammatory markers (CRP, procalcitonin, WBC) trending downward?

- Has source control been achieved (drainage of abscess, removal of infected device)?

- Does the patient remain febrile or clinically deteriorating?

De-escalation Options:

- Narrow the spectrum: Switch from carbapenem to third-generation cephalosporin if ESBL-negative E. coli identified

- Discontinue redundant coverage: Stop vancomycin if MRSA ruled out by negative cultures

- Reduce number of agents: Discontinue combination therapy if mono therapy adequate

- Shorten duration: Transition to oral agents and plan treatment completion

Clinical Stability Indicators

Before de-escalating antibiotics in sepsis patients, ensure clinical stability using these objective criteria:

- Heart rate ≤100 beats/minute

- Respiratory rate ≤24 breaths/minute

- Systolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg without vasopressors

- Temperature 36-38°C (96.8-100.4°F)

- Oxygen saturation ≥90% on room air or baseline oxygen requirement

- Improving mental status (alert and oriented)

- Ability to tolerate oral intake (if considering oral step-down)

Multiple studies confirm that antibiotic de-escalation based on these criteria is safe and does not increase mortality in critically ill patients, including those with negative cultures. In fact, inappropriate prolonged broad-spectrum therapy increases risks of:

- Secondary fungal infections

- Clostridioides difficile infection (20-30% increased risk)

- Antimicrobial resistance development

- Unnecessary drug toxicity

- Extended hospital length of stay

For MBBS students, the key principle is systematic reassessment: empiric broad-spectrum therapy should never be “set and forget.” During ward rounds, actively participate in antibiotic timeouts, reviewing culture data and clinical parameters to recommend appropriate de-escalation to your supervising physicians.

Read More : Approach to Unconscious Patient: Causes, Diagnosis, and Emergency Management

Optimal Duration for Community-Acquired Pneumonia Antibiotics

Determining optimal duration for community-acquired pneumonia antibiotics represents a common clinical scenario where evidence-based stewardship significantly impacts patient outcomes. Traditional approaches recommended 7-14 days of antibiotic therapy, but recent evidence supports shorter courses for appropriately selected patients.

Evidence-Based Duration Guidelines (2025 Update)

The 2025 guidelines for respiratory tract infection guidelines adopt a personalized approach based on clinical stability achievement:

3-Day Treatment:

- Indication: Non-severe CAP with clinical stability achieved by Day 3

- Patient profile: Young adults (<65 years), minimal comorbidities, rapid clinical response

- Evidence: Randomized trials demonstrate non-inferiority compared to longer courses

- Antibiotic examples: Amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, doxycycline

5-Day Treatment:

- Indication: Moderate CAP with clinical stability achieved by Day 5

- Patient profile: Adults with comorbidities, hospitalized patients responding to therapy

- Evidence: Meta-analyses confirm equivalent outcomes to 7-10 day courses

- Antibiotic examples: Respiratory fluoroquinolones, β-lactams, macrolides

7-Day Treatment:

- Indication: Uncomplicated CAP in older adults or those with delayed stability

- Patient profile: Elderly patients (>65 years), multiple comorbidities, slower response

- Evidence: Standard recommendation for most hospitalized CAP cases

- Antibiotic examples: Any appropriate antibiotic based on severity and pathogens

Extended Duration (10-14 Days):

- Indication: Complicated CAP with bacteremia, cavitation, or specific pathogens

- Specific scenarios:

- Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia (minimum 14 days)

- Necrotizing pneumonia with abscess (14-21 days based on imaging)

- Legionella pneumophila in immunocompromised hosts (14 days)

- Inadequate source control or delayed clinical response

The critical paradigm shift: treatment duration should be individualized based on clinical stability achievement rather than arbitrary calendar days. This approach reduces antibiotic exposure by 30-40% without compromising outcomes, significantly decreasing resistance selection pressure and adverse events.

Duration Comparison Table

| Clinical Scenario | Traditional Duration | Evidence-Based Duration | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncomplicated CAP (young, healthy) | 7-10 days | 3 days | 57-70% |

| Hospitalized CAP (stable at Day 5) | 10 days | 5 days | 50% |

| Elderly CAP (uncomplicated) | 10-14 days | 7 days | 30-50% |

| Bacteremic pneumococcal CAP | 10-14 days | 5-7 days | 40% |

| S. aureus pneumonia | 14-21 days | 14 days | Unchanged |

- Assess clinical stability daily using objective criteria

- Document stability achievement date

- Plan treatment completion 3-7 days from stability (depending on severity)

- Avoid reflexive 10-14 day prescriptions without clinical indication

- Educate patients that shorter courses are evidence-based, not substandard care

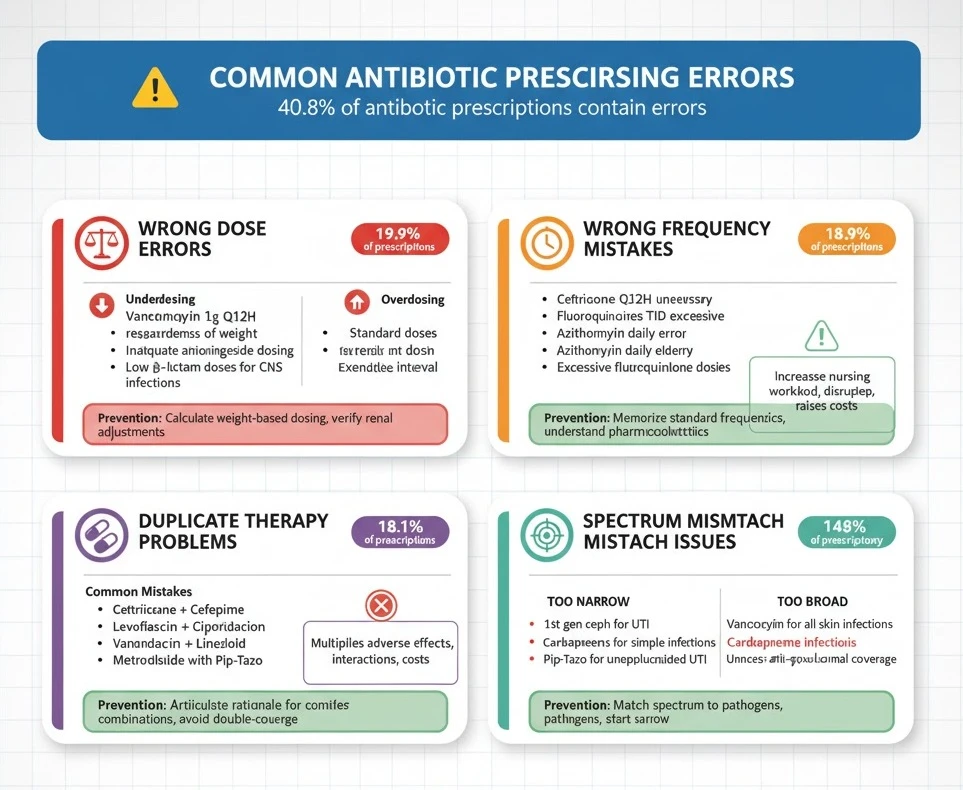

Common Antibiotic Prescribing Errors Medical Students Make

Understanding common antibiotic prescribing errors helps medical students avoid dangerous pitfalls during early clinical practice. A comprehensive study of hospitalized patients found prescribing errors in 40.8% of antibiotic courses, with wrong dose, wrong frequency, and duplicate therapy being most common.

Wrong Dose Errors

Underdosing represents the most frequent dosing error, occurring in approximately 20% of antibiotic prescriptions among hospitalized patients. Medical students often fail to adjust doses appropriately for patient weight, infection severity, or site of infection.

Common Underdosing Mistakes:

- Prescribing standard vancomycin 1 gram every 12 hours regardless of weight (should be 15-20 mg/kg/dose)

- Using standard ciprofloxacin 400 mg IV for serious Pseudomonas infections (requires 400 mg every 8 hours)

- Inadequate aminoglycoside dosing for severe sepsis (should use 5-7 mg/kg for gentamicin/tobramycin)

- Failing to increase β-lactam doses for central nervous system infections (meningitis requires higher doses for CSF penetration)

Overdosing Risks:

- Prescribing standard doses in severe renal impairment without adjustment

- Failing to reduce aminoglycoside doses in elderly patients with reduced muscle mass

- Excessive fluoroquinolone doses increasing seizure and QT prolongation risk

Prevention Strategy:

Always calculate weight-based dosing for vancomycin, aminoglycosides, and daptomycin. Use institutional dosing guidelines or reliable references like Sanford Guide. Double-check renal dose adjustments using creatinine clearance calculators before prescribing renally-eliminated antibiotics.

Wrong Frequency Mistakes

Wrong frequency errors occur in approximately 19% of antibiotic prescriptions, often involving prescribing more frequent administration than necessary or using inappropriate dosing intervals.

Common Frequency Errors:

- Prescribing ceftriaxone every 12 hours (unnecessary; once daily dosing adequate for most infections)

- Using fluoroquinolones three times daily (twice daily sufficient)

- Administering azithromycin daily beyond Day 1 in community settings (once daily is correct)

- Inappropriate extended-interval aminoglycoside dosing in unstable patients (requires traditional dosing)

More-Frequent-Than-Needed Prescribing:

Prescribing antibiotics more frequently than pharmacologically necessary increases nursing workload, disrupts patient sleep, raises costs, and doesn’t improve outcomes. Students sometimes confuse frequency requirements between different generations of cephalosporins (ceftriaxone once daily vs. cefazolin every 8 hours).

Prevention Strategy:

Memorize standard dosing frequencies for commonly used antibiotics. When uncertain, consult pharmacy colleagues or institutional guidelines. Understand pharmacokinetic principles—time-dependent antibiotics (β-lactams) require frequent dosing to maintain concentrations above MIC, while concentration-dependent antibiotics (fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides) can be dosed less frequently with higher individual doses.

Duplicate Therapy Problems

Duplicate therapy—prescribing two antibiotics from the same class or with overlapping spectra without justification—occurs in approximately 18% of prescriptions. This error particularly affects lower respiratory tract infections where students feel pressure to provide “aggressive” coverage.

Common Duplication Mistakes:

- Prescribing both ceftriaxone and cefepime (both are cephalosporins; one suffices)

- Combining levofloxacin and ciprofloxacin (both fluoroquinolones with similar spectra)

- Using vancomycin plus linezolid (both provide MRSA coverage; combination unnecessary and increases toxicity risk)

- Prescribing metronidazole with piperacillin-tazobactam or meropenem (these agents already cover anaerobes)

Inappropriate Combination Therapy:

While combination therapy is appropriate for specific situations (empiric sepsis coverage, anti-pseudomonal therapy), many students prescribe combinations reflexively without clear indication. Each additional antibiotic multiplies adverse effect risk, drug interaction potential, and cost.

Prevention Strategy:

Before prescribing combination therapy, articulate the specific rationale (e.g., “covering both Gram-positives and Gram-negatives in neutropenic fever”). Avoid “double-covering” the same organisms unless specifically indicated for synergy (e.g., beta-lactam plus aminoglycoside for Enterococcus endocarditis) or preventing resistance (tuberculosis treatment).

Spectrum Mismatch Issues

Spectrum mismatch—prescribing antibiotics that don’t cover the causative pathogen or using unnecessarily broad coverage—represents a fundamental stewardship failure.

Too-Narrow Spectrum Errors:

- Using first-generation cephalosporins for Gram-negative UTI (poor E. coli coverage)

- Prescribing penicillin VK for suspected MRSA skin infection

- Using standard ampicillin for E. coli (high resistance rates)

Too-Broad Spectrum Errors:

- Reflexively prescribing vancomycin for all skin infections (most are MSSA, not MRSA)

- Using carbapenems for simple community-acquired infections

- Prescribing piperacillin-tazobactam for uncomplicated UTI (massive overkill)

- Starting anti-pseudomonal coverage without risk factors for Pseudomonas

Prevention Strategy:

Always match antibiotic spectrum to suspected/confirmed pathogens. Start with narrow-spectrum agents and broaden only if clinically indicated. Remember that broader isn’t better—it’s often worse due to increased resistance selection and adverse effects.

Error Summary Table

| Error Type | Frequency | High-Risk Situations | Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wrong Dose | 19.9% | Renal impairment, extremes of weight | Calculate doses, verify renal adjustments |

| Wrong Frequency | 18.9% | Long-acting agents given too often | Consult formulary, understand pharmacokinetics |

| Duplicate Therapy | 18.1% | Respiratory infections, sepsis | Review all antimicrobials before adding agents |

| Spectrum Mismatch | Variable | Empiric therapy, unusual organisms | Use antibiogram, consult ID when uncertain |

Case-Based Learning: Antibiotic Stewardship in Action

Antibiotic stewardship for MBBS students becomes concrete through case-based application. These scenarios illustrate principles in realistic clinical contexts you’ll encounter during rotations.

Case 1: UTI in Young Female

Presentation:

A 24-year-old otherwise healthy female presents to clinic with 2 days of dysuria, urinary frequency, and suprapubic discomfort. No fever, flank pain, or vaginal symptoms. No antibiotic use in the past year. Urinalysis shows 50+ WBCs, positive nitrites, and few bacteria.

Poor Stewardship Approach:

Prescribe ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily for 7 days based on “coverage” thinking.

Excellent Stewardship Approach:

- Confirm diagnosis: Classic uncomplicated cystitis in young female—no imaging or urine culture needed for initial management

- Check antibiogram: Local E. coli susceptibility shows nitrofurantoin 94%, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 82%, ciprofloxacin 76%

- Select narrowest effective agent: Prescribe nitrofurantoin 100 mg twice daily for 5 days

- Patient education: Explain that fluoroquinolones are reserved for more serious infections; nitrofurantoin is equally effective with less resistance risk

- Follow-up plan: Return if symptoms persist >3 days or worsen, at which point culture and sensitivity testing would guide alternative therapy

Stewardship Points:

- Avoided fluoroquinolone for simple infection (preserves “Watch” category antibiotic)

- Used evidence-based 5-day duration instead of traditional 7-10 days

- Selected agent with highest local susceptibility

- No unnecessary urine culture in uncomplicated case (reduces healthcare costs)

Case 2: Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Presentation:

A 68-year-old male with hypertension and diabetes presents to emergency department with 3 days of productive cough, fever to 102°F, and dyspnea. Vitals: BP 135/82, HR 98, RR 24, O2 sat 91% on room air. Chest X-ray shows right lower lobe infiltrate. No recent hospitalization or antibiotic use.

Poor Stewardship Approach:

Admit to hospital. Start vancomycin 1 gram IV every 12 hours plus piperacillin-tazobactam 4.5 grams IV every 6 hours for “broad coverage” with plan for 10-14 days total.

Excellent Stewardship Approach:

- Risk stratification: Calculate PORT/PSI score = Class III (low-intermediate risk); consider outpatient vs. observation management

- Pathogen consideration: Community-acquired, no healthcare risk factors—most likely S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, atypical pathogens. MRSA and Pseudomonas unlikely.

- Admit for observation: Given age, comorbidities, and hypoxia

- Appropriate empiric therapy: Ceftriaxone 1 gram IV daily plus azithromycin 500 mg IV/PO daily

- Culture stewardship: Obtain blood cultures (bacteremia risk ~5-10% in hospitalized CAP), sputum culture if productive

- 48-hour timeout: Review cultures and clinical response. Blood cultures negative, patient afebrile, oxygen requirement resolved → discontinue azithromycin after 1-2 doses (atypical coverage adequate)

- Early transition: Switch ceftriaxone to oral amoxicillin-clavulanate on Day 3 when clinically stable

- Duration: Plan 5-day total course from initiation, resulting in hospital discharge Day 3-4 with 1-2 days oral completion at home

Stewardship Points:

- Avoided unnecessary broad-spectrum therapy (vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam)

- Appropriate empiric coverage for community pathogens

- Early de-escalation based on negative cultures and clinical stability

- Evidence-based 5-day duration instead of arbitrary 10-14 days

- Early oral transition (reduces IV line complications and hospital length of stay)

Case 3: Hospital-Acquired Sepsis

Presentation:

A 72-year-old female on Day 7 following hip replacement develops fever to 103°F, hypotension (BP 85/50), tachycardia (HR 125), and altered mental status. Foley catheter in place. Urine is cloudy. Labs show WBC 18,000, creatinine 1.8 (baseline 0.9). Lactate 3.2 mmol/L.

Poor Stewardship Approach:

Start meropenem 1 gram IV every 8 hours plus vancomycin 1 gram IV every 12 hours plus micafungin 100 mg IV daily. Plan for 14-21 days of therapy.

Excellent Stewardship Approach:

Hour 0-1 (Emergency Management):

-

Recognize septic shock: Meet Sepsis-3 criteria with organ dysfunction

-

Immediate cultures: Blood cultures × 2, urine culture before antibiotics

-

Broad empiric coverage: Reasonable initial choice given healthcare-associated infection, but adjust doses:

-

Vancomycin 15-20 mg/kg IV (weight-based dosing, targeting trough 15-20)

-

Piperacillin-tazobactam 3.375 grams IV every 6 hours (renal-adjusted dose for CrCl 20-40)

-

-

Source control: Remove Foley catheter (likely source)

-

Supportive care: Aggressive fluid resuscitation per sepsis bundle

Hour 48-72 (Antibiotic Timeout):

-

Review cultures: Urine culture growing E. coli >100,000 CFU/mL, susceptible to ceftriaxone, cefepime, piperacillin-tazobactam; resistant to ampicillin, ciprofloxacin. Blood cultures negative × 2 sets.

-

Clinical assessment: Patient improved—BP 118/70 off pressors, lactate normalized, afebrile, mental status returned to baseline

-

De-escalation decision:

-

STOP vancomycin (no Gram-positive infection identified)

-

CHANGE piperacillin-tazobactam to ceftriaxone 1 gram IV daily (narrower spectrum, once-daily dosing, adequate E. coli coverage)

-

-

Duration planning: Uncomplicated urosepsis with source control (catheter removed) and rapid response → plan 7-day total course

Day 5-7 (Completion):

- Oral transition: Switch to oral cefpodoxime 200 mg twice daily when tolerating oral intake

- Discharge planning: Complete remaining 2-3 days as outpatient

- Follow-up: Clinic appointment 1-2 weeks post-treatment to ensure resolution

Stewardship Points:

- Appropriate initial broad empiric coverage for septic shock

- Prompt de-escalation based on cultures and clinical stability (48-hour timeout)

- Avoided prolonged vancomycin (would have increased nephrotoxicity risk)

- Transitioned to targeted narrow-spectrum therapy

- Evidence-based 7-day duration for complicated UTI with bacteremia ruled out

- Early discharge with oral completion (patient-centered, cost-effective)

Read More : Complete Blood Count Interpretation: Red Flags, Clinical Correlates & Exam Caselets

Antibiotic Stewardship Best Practices Checklist

This safe prescribing checklist for antibiotics provides a practical tool for medical students during clinical rotations. Print this or save it on your mobile device for quick reference during ward rounds.

Pre-Prescription Phase

Diagnostic Confirmation

- Objective evidence of bacterial infection present (not viral syndrome)

- Appropriate cultures obtained before antibiotic initiation when feasible

- Alternative diagnoses considered and ruled out

- Site of infection clearly identified

Patient Assessment

- Allergies documented with specific reaction types

- Current medications reviewed for interactions

- Renal function assessed (calculate CrCl)

- Hepatic function evaluated

- Weight documented for dose calculations

- Pregnancy status confirmed in females of childbearing age

Pathogen Prediction

- Likely organisms identified based on infection site and patient factors

- Healthcare-associated vs. community-acquired status determined

- Recent antibiotic exposure history obtained (past 90 days)

- Risk factors for resistant organisms evaluated

Prescription Phase

Antibiotic Selection

- Local antibiogram consulted

- Narrowest-spectrum agent selected

- WHO AWaRe classification considered (prefer Access category)

- Drug penetration adequate for infection site

- Oral vs. IV route appropriate for severity

Dosing Accuracy

- Dose calculated correctly (weight-based when indicated)

- Frequency appropriate for antibiotic pharmacokinetics

- Route of administration optimal

- Renal/hepatic dose adjustments applied

- Loading dose given when indicated (vancomycin, aminoglycosides in severe infections)

Documentation

- Indication clearly documented in medical record

- Duration specified (not just “continue”)

- Stop date or review date noted

- Rationale for broad-spectrum agents justified

Monitoring Phase

48-72 Hour Timeout

- Culture results reviewed

- Clinical response assessed (temperature trend, vital signs, symptom improvement)

- Inflammatory markers trended (if obtained)

- De-escalation opportunity evaluated

- Duration reassessed based on response

Ongoing Monitoring

- Drug levels checked when indicated (vancomycin, aminoglycosides)

- Adverse effects monitored (rash, GI symptoms, organ toxicity)

- Drug interactions reassessed with any medication changes

- Consideration of C. difficile risk with diarrhea development

Completion Phase

Treatment Duration

- Evidence-based duration applied (not arbitrary)

- Extended only for documented clinical indication

- Oral transition made when appropriate (bioavailability, patient tolerating oral intake)

- Patient counseling on completion importance

Follow-up Planning

- Clear instructions for treatment completion

- Return precautions explained (worsening symptoms, adverse effects)

- Follow-up appointment scheduled when indicated

- Culture repeat planned only if clinically indicated

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q : What is antibiotic stewardship and why is it important for medical students?

A : Antibiotic stewardship is a coordinated program that promotes the appropriate use of antimicrobials to improve patient outcomes, reduce microbial resistance, and decrease the spread of infections caused by multidrug-resistant organisms. For medical students, mastering stewardship principles is critical because you will soon independently prescribe antibiotics that can either help or harm patients while contributing to or combating the global resistance crisis that causes over 1.27 million deaths annually.

Q : What are the main principles of antibiotic stewardship that MBBS students should know?

A : The principles of antibiotic stewardship for students include seven core elements: leadership commitment, clear accountability, drug expertise through pharmacist involvement, implementation of evidence-based actions like prospective audit and feedback, tracking of prescribing patterns through antibiograms, regular reporting of outcomes, and continuous education on optimal prescribing. Additionally, students should understand the WHO AWaRe classification system that categorizes antibiotics into Access (first-line), Watch (broader-spectrum), and Reserve (last-resort) categories to guide prescribing decisions.

Q : How can medical students avoid common antibiotic prescribing errors?

A : Medical students can avoid common prescribing errors by systematically following a pre-prescription checklist that includes confirming infection presence, assessing allergies, calculating weight-based doses, checking renal function, and consulting local antibiograms before prescribing. The most frequent errors involve wrong dose (particularly underdosing), wrong frequency, duplicate therapy, and spectrum mismatch—all preventable through careful verification using institutional guidelines, pharmacy consultation, and understanding basic antibiotic pharmacokinetics.

Q : When should antibiotics be de-escalated in sepsis patients?

A : Antibiotics should be de-escalated at 48-72 hours after initiation through a systematic “antibiotic timeout” that reviews microbiological culture results and assesses clinical stability indicators including heart rate ≤100/min, respiratory rate ≤24/min, systolic BP ≥90 mmHg without vasopressors, temperature 36-38°C, and oxygen saturation ≥90%. De-escalation involves narrowing antibiotic spectrum based on susceptibility results, discontinuing redundant coverage, or reducing the number of agents while maintaining effective therapy—a strategy proven safe even in critically ill patients with negative cultures.

Q : What is the optimal duration of antibiotic treatment for community-acquired pneumonia?

A : The optimal duration for community-acquired pneumonia antibiotics depends on achieving clinical stability rather than arbitrary calendar days. Current 2025 guidelines recommend 3-day treatment for non-severe CAP stabilized by Day 3 in young patients with minimal comorbidities, 5-day treatment for moderate CAP achieving stability by Day 5, 7-day treatment for uncomplicated CAP in elderly patients or those with delayed stability, and only 10-14 days for complicated cases involving bacteremia, cavitation, or specific pathogens like S. aureus.

Q : How do you read an antibiogram correctly?

A : To read an antibiogram, locate your suspected organism in the rows, find antibiotic options in the columns, and identify the percentage value where they intersect representing the proportion of isolates susceptible to that antibiotic. Select antibiotics with ≥85% susceptibility for empiric therapy, use caution with 70-84% susceptibility, and avoid agents with <70% susceptibility unless culture-directed. Remember that antibiograms reflect institutional data from at least 30 isolates and may not represent all populations or infection sites.

Exam Question-Answer Section: University Pattern

Question 1: Long Essay (15 marks)

A 65-year-old diabetic male presents with community-acquired pneumonia. Discuss the principles of antibiotic stewardship in managing this patient, including empiric therapy selection, de-escalation strategies, and appropriate treatment duration.

Model Answer (Bullet-Point Format):

Introduction (1 mark)

- Define antibiotic stewardship as coordinated interventions to optimize antimicrobial use

- Emphasize balancing effective treatment with resistance prevention

- Mention relevance to CAP management in comorbid patients

Initial Assessment and Risk Stratification (2 marks)

- Calculate severity scores (PORT/PSI or CURB-65)

- Assess risk factors: diabetes, age >65, comorbidities

- Determine admission vs. outpatient management

- Obtain appropriate cultures (blood, sputum if productive)

Empiric Therapy Selection (3 marks)

- Likely pathogens: S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, atypical organisms

- Diabetes increases risk of S. aureus but not MRSA in community setting

- Evidence-based empiric regimen: β-lactam (ceftriaxone) plus macrolide OR respiratory fluoroquinolone monotherapy

- Rationale: Narrow-spectrum coverage adequate for community pathogens

- Avoid broad-spectrum agents (vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam) without risk factors

- Dose adjustments for renal function if present

48-72 Hour Antibiotic Timeout (3 marks)

- Review culture results systematically

- Assess clinical stability (afebrile, improved oxygenation, hemodynamic stability)

- De-escalation strategies:

-

Stop macrolide if blood cultures negative and patient improved

-

Continue β-lactam targeted to identified pathogen

-

Transition IV to oral when tolerating intake and stable

-

Treatment Duration (2 marks)

- 2025 guidelines: Personalized based on stability achievement

- Non-severe CAP stable at Day 3: 3-day total course

- Hospitalized CAP stable at Day 5: 5-day total course

- Complicated cases (bacteremia, slow response): 7 days

- Avoid arbitrary 10-14 day courses without indication

Monitoring and Follow-up (2 marks)

- Monitor clinical response (temperature, oxygen requirements)

- Check for adverse effects (drug interactions with diabetes medications)

- Patient education on completion importance

- Follow-up appointment to confirm resolution

Stewardship Principles Applied (2 marks)

- Narrow-spectrum empiric therapy

- Evidence-based duration (not excessive)

- Systematic de-escalation at 48-72 hours

- Oral transition when appropriate

- Documentation of indication and planned duration

Diagram Prompt:

Draw a flowchart showing decision points from admission through treatment completion, including initial empiric therapy, 48-hour timeout with de-escalation options, and duration determination based on stability.

Question 2: Short Essay (10 marks)

Enumerate common antibiotic prescribing errors in medical practice. Discuss strategies to prevent these errors.

Model Answer:

Common Prescribing Errors (5 marks)

-

Wrong Dose Errors (1 mark)

- Underdosing: Failing weight-based calculations for vancomycin, aminoglycosides

- Overdosing: Not adjusting for renal/hepatic impairment

- Examples: Standard vancomycin dose ignoring patient weight

-

Wrong Frequency Mistakes (1 mark)

- More frequent than necessary (ceftriaxone Q12H instead of Q24H)

- Inappropriate intervals affecting efficacy

- Confusion between antibiotic generations

-

Duplicate Therapy (1 mark)

- Prescribing two agents from same class

- Overlapping spectrum without justification

- Example: Ceftriaxone plus cefepime simultaneously

-

Spectrum Mismatch (1 mark)

- Too narrow: Penicillin VK for MRSA

- Too broad: Carbapenems for simple UTI

- Not consulting antibiogram for local resistance

-

Duration Errors (1 mark)

- Arbitrary prolonged courses (10-14 days for all infections)

- Premature discontinuation before stability achieved

- Not documenting stop dates

Prevention Strategies (5 marks)

-

Systematic Checklists (1 mark)

- Use pre-prescription assessment tools

- Verify allergies, weight, renal function before prescribing

- Consult institutional guidelines for standard dosing

-

Antibiogram Utilization (1 mark)

- Reference local susceptibility data before empiric therapy

- Select narrowest-spectrum agent with ≥85% susceptibility

- Update antibiogram annually and use current version

-

Pharmacist Collaboration (1 mark)

- Consult pharmacy for dose verification

- Utilize pharmacist-led prospective audit and feedback

- Participate in antimicrobial stewardship rounds

-

48-72 Hour Timeout Protocol (1 mark)

- Mandatory review of cultures and clinical response

- De-escalation or discontinuation decisions

- Avoid “set and forget” prescribing

-

Education and Training (1 mark)

- Participate in stewardship educational programs

- Case-based learning of optimal prescribing

- Regular updates on resistance patterns and guidelines

Viva Voce Tips

Common Examiner Questions:

- “Why shouldn’t you prescribe fluoroquinolones for simple UTI?” – Emphasize stewardship, preserving broad-spectrum agents

- “When would you use carbapenems?” – Reserve category, ESBL organisms, severe sepsis with resistant Gram-negatives

- “What is the ‘antibiotic timeout’?” – 48-72 hour systematic review for de-escalation

- “Name three criteria for clinical stability in pneumonia” – HR ≤100, RR ≤24, SBP ≥90, temp 36-38°C, O2 sat ≥90%

Examiner Favorites:

- Ask you to calculate a dose (know vancomycin 15-20 mg/kg/dose)

- Differentiate community vs. healthcare-associated infection

- Explain WHO AWaRe classification

- Discuss antibiotic-related adverse effects (C. difficile, QT prolongation, nephrotoxicity)

Last-Minute Checklist Before Exam

Core Definitions

- Antibiotic stewardship definition memorized

- Seven CDC Core Elements listed

- WHO AWaRe categories (Access/Watch/Reserve) understood

Practical Skills

- Can read sample antibiogram correctly

- Know how to calculate vancomycin dose (15-20 mg/kg)

- Can list clinical stability criteria for de-escalation

Common Errors

- Four types of prescribing errors memorized (dose, frequency, duplicate, spectrum)

- Prevention strategies for each error type

Evidence-Based Durations

- CAP durations: 3 days (stable Day 3), 5 days (stable Day 5), 7 days (uncomplicated)

- Sepsis de-escalation timing: 48-72 hours

- UTI duration: 5 days uncomplicated cystitis

Case Approach

- Can outline systematic antibiotic selection process

- Understand empiric → targeted therapy progression

- Know when to consult infectious disease specialist

Conclusion

Mastering antibiotic stewardship: principles, common errors, and safe prescribing for MBBS students represents one of the most impactful clinical skills you’ll develop during medical training. Every antibiotic prescription you write carries consequences extending far beyond your individual patient—to their microbiome, to other patients who may acquire resistant organisms, and to the global community facing the existential threat of antimicrobial resistance.

By systematically applying the principles of antibiotic stewardship—consulting antibiograms, choosing narrow-spectrum agents, performing 48-72 hour timeouts, and using evidence-based durations—you transform from a student who prescribes reactively into a physician who prescribes responsibly. The safe antibiotic prescribing framework outlined in this guide provides practical tools you can implement immediately during clinical rotations, from pre-prescription checklists to case-based decision-making strategies.

Remember, antimicrobial stewardship isn’t an optional academic concept—it’s your professional responsibility as a future physician. Start building these habits now, and you’ll protect countless patients throughout your career while preserving antibiotics for future generations.

Ready to deepen your medical knowledge? Subscribe to the Simply MBBS newsletter for weekly clinical pearls, exam-focused guides, and evidence-based insights delivered straight to your inbox. Visit simplymbbs.com today for more essential MBBS resources, including clinical rotation tips, pharmacology guides, and exam preparation strategies that simplify complex medical concepts for students worldwide.