Did you know that Acute Kidney Injury affects nearly 1 in 5 hospitalized patients worldwide, yet many cases go unrecognized until severe complications develop? This sudden decline in kidney function can escalate from a minor lab abnormality to life-threatening organ failure within hours, making early detection and prompt intervention absolutely critical for patient survival and recovery.

Acute Kidney Injury (AKI), formerly known as acute renal failure, represents one of the most challenging conditions in modern medicine, affecting everyone from trauma victims and surgical patients to individuals with chronic diseases like diabetes and heart failure. Unlike chronic kidney disease that develops gradually over years, AKI strikes suddenly—often as a complication of another serious illness—demanding immediate medical attention and sophisticated management strategies.

This comprehensive guide walks you through everything medical students, healthcare professionals, and informed patients need to understand about Acute Kidney Injury—from the molecular pathophysiology and standardized KDIGO criteria for AKI to practical bedside diagnosis using urine indices and evidence-based AKI management protocols. Whether you’re preparing for MBBS exams, managing patients in the emergency department, or simply seeking to understand kidney health, this article provides clear, actionable insights grounded in the latest medical evidence and clinical guidelines.

What is Acute Kidney Injury?

Acute Kidney Injury is defined as an abrupt decrease in kidney function occurring within 48 hours to 7 days, characterized by the accumulation of waste products like creatinine and urea in the blood, along with dysregulation of fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base balance. According to the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) working group—the internationally accepted standard—AKI is diagnosed when any of the following criteria are met :

- Increase in serum creatinine rise in AKI by ≥0.3 mg/dL (≥26.5 µmol/L) within 48 hours

- Increase in serum creatinine to ≥1.5 times baseline, which is known or presumed to have occurred within the prior 7 days

- Oliguria definition: Urine volume <0.5 mL/kg/hour for 6 hours

Unlike chronic kidney disease where structural damage accumulates over months to years, Acute Kidney Injury represents a potentially reversible condition if identified early and treated appropriately. The kidneys possess remarkable regenerative capacity, and many patients with AKI can recover normal or near-normal renal function with proper supportive care, though the injury increases long-term risk for developing chronic kidney disease.

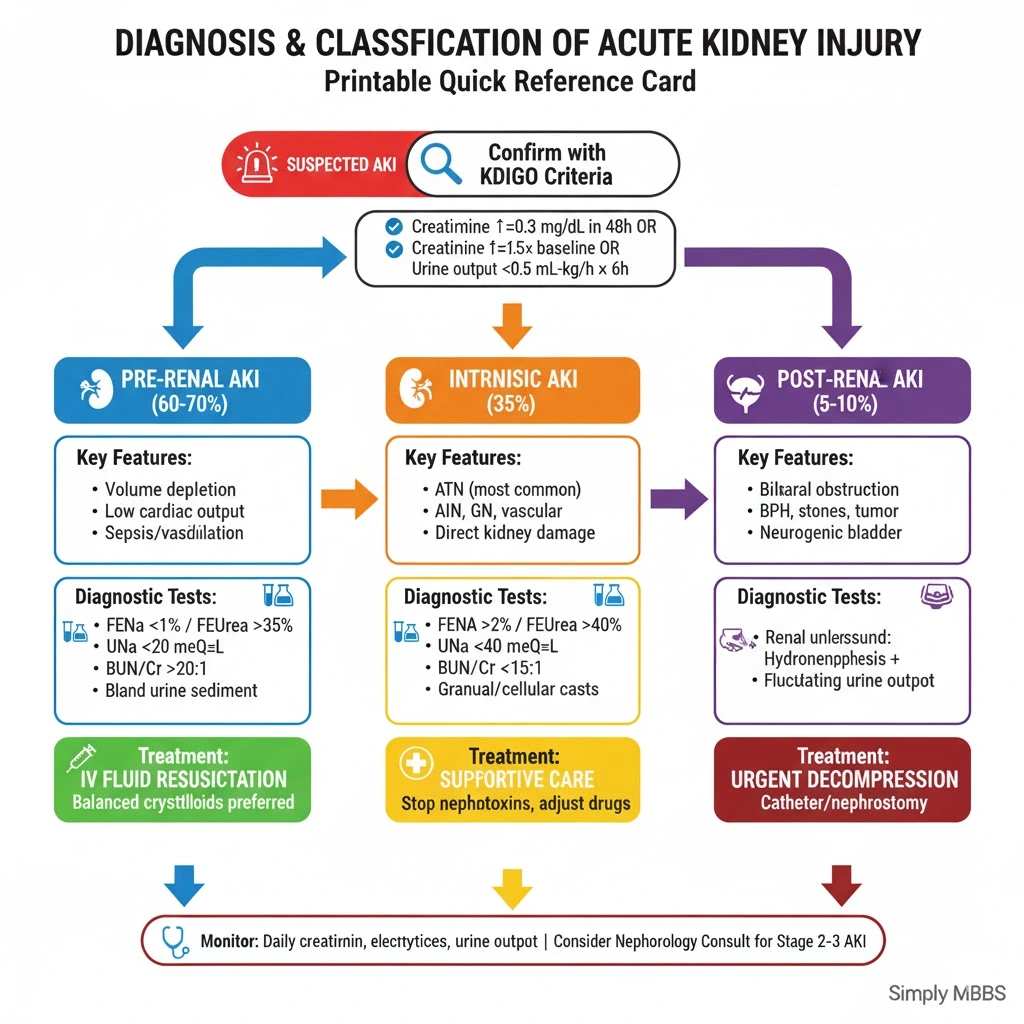

The pathophysiology involves injury to various kidney structures—glomeruli, tubules, interstitium, or renal vasculature—resulting from reduced blood flow (pre-renal), direct tissue damage (intrinsic renal), or urinary tract obstruction (post-renal). Understanding this classification system is fundamental to proper AKI diagnosis and management strategies.

Why Acute Kidney Injury Matters

Clinical Significance & Impact

Acute Kidney Injury represents far more than just abnormal laboratory values—it’s a systemic condition that affects every organ system and carries profound implications for patient outcomes. Studies demonstrate that even mild AKI (Stage 1) increases in-hospital mortality risk by 2-3 fold, while severe AKI requiring dialysis carries mortality rates exceeding 50% in intensive care settings.

For Medical Students & Healthcare Professionals:

The importance of mastering AKI cannot be overstated for several critical reasons :

- High Prevalence: Affects 10-15% of all hospitalized patients and up to 50% of ICU admissions

- Early Detection: Recognizing subtle creatinine rise in AKI patterns prevents progression to severe stages

- Differential Diagnosis: Distinguishing pre-renal vs intrinsic vs post-renal AKI guides completely different treatment approaches

- Drug Dosing: Many medications require adjustment in AKI, and some drugs (NSAIDs, contrast agents, aminoglycosides) directly cause kidney injury

- Systemic Effects: AKI disrupts fluid balance, electrolytes (causing dangerous hyperkalemia), acid-base status, and alters the metabolism of other organs

For Patients & General Public:

Understanding Acute Kidney Injury empowers individuals to recognize warning signs early and seek timely medical intervention. The condition often develops silently in hospitalized patients or following major surgeries, infections, severe dehydration, or medication reactions. Risk factors include age over 65, pre-existing chronic kidney disease, diabetes, heart failure, liver disease, and use of certain medications like NSAIDs or antibiotics.

Early symptoms may include decreased urine output, swelling in legs and ankles, fatigue, confusion, nausea, chest pressure, and shortness of breath. However, mild cases may produce no symptoms at all, highlighting the importance of blood test monitoring in at-risk individuals. For patients with conditions like diabetic ketoacidosis complications or heart failure and kidney dysfunction, regular kidney function monitoring becomes essential preventive care.

Acute Kidney Injury Classification Systems: RIFLE vs AKIN vs KDIGO

Understanding the evolution of AKI classification systems provides essential context for modern diagnosis and research interpretation. Three major classification schemes have shaped our approach to defining and staging Acute Kidney Injury.

RIFLE Criteria (2004)

The Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, End-Stage (RIFLE) classification was the first consensus definition, establishing five categories based on creatinine rise in AKI or glomerular filtration rate (GFR) changes :

Severity Stages:

- Risk: Serum creatinine increased 1.5× OR GFR decreased >25% OR urine output <0.5 mL/kg/h for 6 hours

- Injury: Serum creatinine increased 2.0× OR GFR decreased >50% OR urine output <0.5 mL/kg/h for 12 hours

- Failure: Serum creatinine increased 3.0× OR GFR decreased >75% OR creatinine ≥4.0 mg/dL with acute rise ≥0.5 mg/dL OR urine output <0.3 mL/kg/h for 24 hours or anuria for 12 hours

Outcome Categories:

- Loss: Persistent acute renal failure >4 weeks

- End-Stage: Kidney disease >3 months

RIFLE criteria demonstrated high sensitivity in detecting early AKI, particularly the “Risk” category, making it valuable for screening.

AKIN Criteria (2007)

The Acute Kidney Injury Network modified RIFLE to improve early detection, creating a simplified three-stage system :

Stage 1: Increase in serum creatinine ≥0.3 mg/dL OR ≥150-200% (1.5-2× fold) from baseline within 48 hours OR urine output <0.5 mL/kg/h for >6 hours

2: Increase in serum creatinine >200-300% (>2-3× fold) from baseline OR urine output <0.5 mL/kg/h for >12 hours

3: Increase in serum creatinine >300% (>3× fold) OR creatinine ≥4.0 mg/dL with acute increase ≥0.5 mg/dL OR initiation of renal replacement therapy OR urine output <0.3 mL/kg/h for ≥24 hours or anuria for ≥12 hours

The key innovation was adding the absolute increase criterion (≥0.3 mg/dL) to catch early AKI even when percentage changes seemed small.

KDIGO Criteria (2012) – Current Standard

The KDIGO criteria for AKI unified the best elements of RIFLE and AKIN, becoming the internationally accepted standard for AKI diagnosis and staging :

Diagnostic Criteria (ANY of the following):

- Increase in serum creatinine by ≥0.3 mg/dL (≥26.5 μmol/L) within 48 hours

- Increase in serum creatinine to ≥1.5 times baseline, known or presumed to have occurred within prior 7 days

- Urine volume <0.5 mL/kg/hour for 6 hours

Comparative Analysis Table:

| Feature | RIFLE | AKIN | KDIGO |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Stages | 5 (3 severity + 2 outcome) | 3 | 3 |

| Time Window | 7 days | 48 hours | 48 hours + 7 days |

| Minimum Creatinine Increase | 1.5× baseline | 0.3 mg/dL or 1.5× | 0.3 mg/dL or 1.5× |

| GFR Included | Yes | No | No |

| Oliguria Definition | Staged by hours | Staged by hours | Staged by hours |

| Sensitivity for Stage 1 | Lower | Higher | Highest |

Research demonstrates that KDIGO identifies more patients with early-stage AKI compared to RIFLE, while maintaining comparable specificity for severe cases. All three systems show that increasing AKI stages correlate strongly with mortality risk, length of hospital stay, and need for renal replacement therapy.

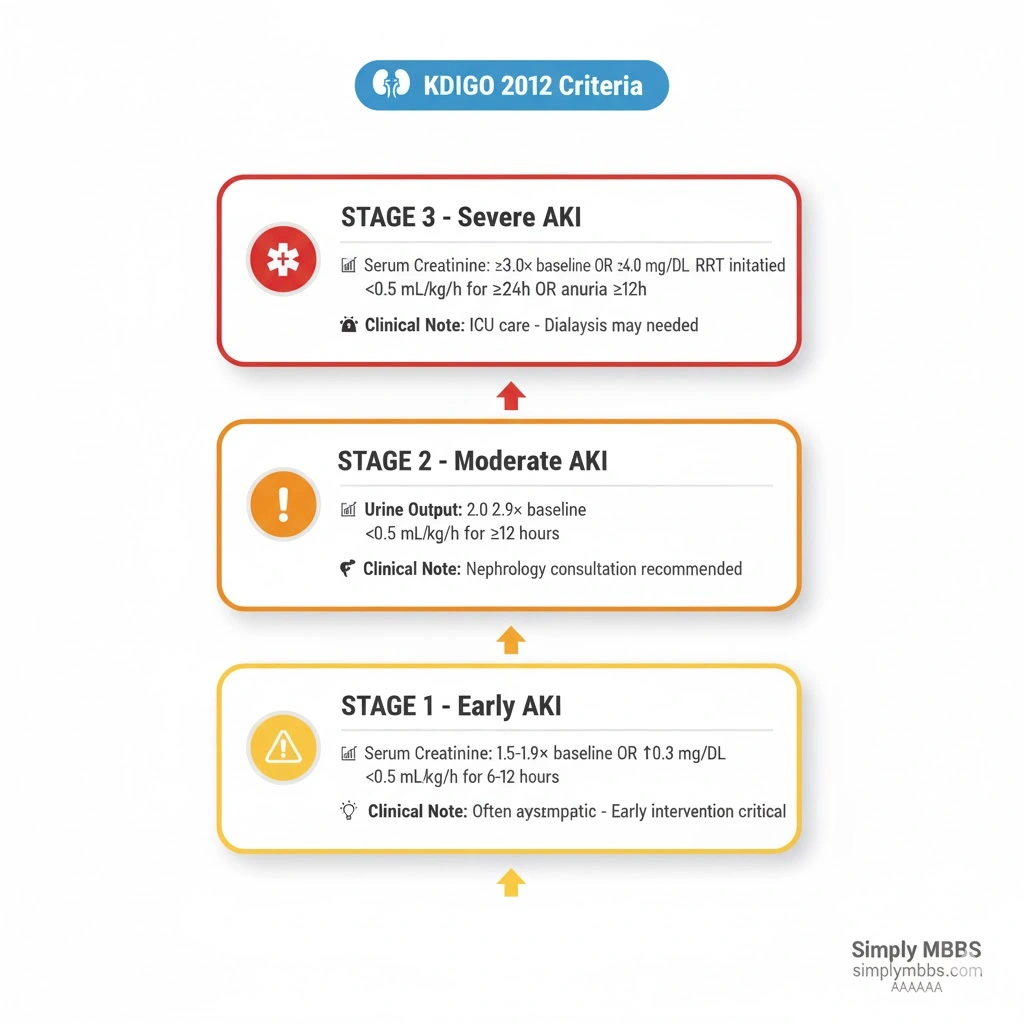

AKI Stages (KDIGO): Complete Clinical Breakdown

Modern AKI stages (KDIGO) provide standardized severity grading that guides treatment intensity and prognostic assessment. Each stage carries distinct clinical implications and management considerations.

Stage 1 AKI: Early Injury

Diagnostic Criteria:

- Serum creatinine 1.5-1.9 times baseline OR

- ≥0.3 mg/dL (≥26.5 µmol/L) increase OR

- Urine output <0.5 mL/kg/hour for 6-12 hours

Clinical Significance: Stage 1 represents the earliest detectable kidney injury phase. While often asymptomatic, even this mild elevation increases mortality risk and predisposes to chronic kidney disease development. Early recognition at this stage allows aggressive preventive measures like discontinuing nephrotoxic medications, optimizing fluid status, and treating underlying causes before progression occurs.

Stage 2 AKI: Moderate Injury

Diagnostic Criteria:

- Serum creatinine 2.0-2.9 times baseline OR

- Urine output <0.5 mL/kg/hour for ≥12 hours

Clinical Significance: Stage 2 indicates more substantial nephron damage with measurable functional impairment. Patients typically exhibit clinical symptoms including reduced urine output, mild fluid overload, and early electrolyte disturbances. This stage requires intensive monitoring, potential nephrology consultation, and consideration of underlying causes needing specific interventions.

Stage 3 AKI: Severe Injury

Diagnostic Criteria:

- Serum creatinine 3.0 times baseline OR

- Increase in serum creatinine to ≥4.0 mg/dL (≥353.6 µmol/L) OR

- Initiation of renal replacement therapy (dialysis) OR

- Urine output <0.3 mL/kg/hour for ≥24 hours OR anuria for ≥12 hours

Clinical Significance: Stage 3 represents critical kidney failure with severe metabolic derangements. Patients develop life-threatening complications including severe hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, fluid overload with pulmonary edema, and uremic symptoms affecting mental status. Immediate nephrology consultation and potential emergency dialysis become necessary. Mortality rates exceed 50% in ICU settings at this stage.

Prognostic Importance: Research consistently demonstrates that each incremental AKI stage escalates risk proportionally—Stage 3 patients face 5-10 times higher mortality compared to Stage 1. Recovery potential inversely correlates with stage severity, emphasizing the critical importance of preventing progression through early intervention at Stage 1.

Pathophysiology: How Acute Kidney Injury Develops

Overview of Kidney Function & Injury Mechanisms

Normal kidney function depends on adequate renal blood flow delivering approximately 20-25% of cardiac output to the kidneys, where glomerular filtration removes waste products while tubules reabsorb essential nutrients and regulate fluid-electrolyte balance. Acute Kidney Injury occurs when any process disrupts this delicate system, reducing the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and impairing waste elimination.

The fundamental pathophysiology involves a cascade of cellular and molecular events :

- Ischemia or Toxin Exposure: Reduced blood flow or nephrotoxic agents damage kidney cells

- Cellular Energy Depletion: ATP depletion disrupts ion pumps and cellular integrity

- Inflammation: Damaged cells release inflammatory mediators attracting immune cells

- Oxidative Stress: Free radical generation causes further cellular injury

- Tubular Obstruction: Cell debris and protein casts block tubules

- Vasoconstriction: Inflammatory mediators cause prolonged renal vasoconstriction

- Epithelial Cell Death: Apoptosis and necrosis of tubular epithelial cells

Understanding the specific mechanisms underlying pre-renal vs intrinsic vs post-renal AKI is essential for targeted therapy.

Pre-Renal AKI: Hypoperfusion Injury

Mechanism: Pre-renal AKI results from inadequate blood flow to structurally normal kidneys, representing 60-70% of community-acquired cases. The kidneys initially attempt compensation through autoregulatory mechanisms—afferent arteriolar dilation and efferent arteriolar constriction maintain glomerular pressure—but sustained hypoperfusion overwhelms these defenses.

Pathophysiological Events:

- Decreased renal blood flow → Reduced GFR

- Activation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) → Sodium and water retention

- Sympathetic nervous system activation → Systemic and renal vasoconstriction

- Antidiuretic hormone (ADH) release → Concentrated urine production

- If prolonged (>30-60 minutes) → Tubular ischemia → Progression to acute tubular necrosis

Common Causes:

Hypovolemia (True Volume Depletion):

- Hemorrhage (trauma, gastrointestinal bleeding)

- Severe dehydration (poor oral intake, heat exposure)

- Gastrointestinal losses (vomiting, diarrhea, high ostomy output)

- Renal losses (overdiuresis, osmotic diuresis in diabetes)

- Third-spacing (burns, pancreatitis, sepsis)

Decreased Cardiac Output:

- Heart failure and cardiogenic shock

- Massive pulmonary embolism

- Cardiac tamponade

- Severe arrhythmias

Systemic Vasodilation:

- Septic shock (most common ICU cause)

- Anaphylaxis

- Anesthesia/sedation effects

Medications Altering Renal Hemodynamics:

- NSAIDs (block prostaglandin-mediated afferent dilation)

- ACE inhibitors/ARBs (block efferent arteriolar constriction)

- Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine, tacrolimus)

- Hepatorenal syndrome

The key distinguishing feature: kidney tubular function remains intact, producing concentrated urine with low urine sodium in AKI (<20 mEq/L) as the kidneys avidly retain sodium. Early recognition and correction of the underlying cause usually leads to complete recovery within 24-48 hours.

Intrinsic Renal AKI: Direct Kidney Damage

Mechanism: Intrinsic (intrarenal) AKI involves direct structural damage to kidney parenchyma—glomeruli, tubules, interstitium, or renal vasculature—accounting for approximately 35-40% of AKI cases.

Acute Tubular Necrosis (ATN) – Most Common Type (85% of intrinsic AKI):

ATN represents the most severe form of intrinsic AKI, typically resulting from prolonged ischemia or nephrotoxin exposure. The pathophysiology includes:

- Ischemic ATN: Prolonged pre-renal state (>60 minutes) causes tubular epithelial cell death, particularly in the proximal tubule and thick ascending limb of Henle (high metabolic demand areas)

- Tubular Obstruction: Dead cells slough into tubular lumen creating casts that obstruct flow

- Backleak: Damaged tubular epithelium allows filtered fluid to leak back into circulation

- Inflammation: Cytokine release perpetuates injury and delays recovery

Common Causes of ATN:

- Prolonged hypotension or shock (surgical, trauma, sepsis-related)

- Nephrotoxic drugs (aminoglycosides, amphotericin B, cisplatin, contrast media)

- Rhabdomyolysis (crush injury, prolonged immobilization, drug overdose)

- Tumor lysis syndrome

- Hemolysis (transfusion reactions)

Other Intrinsic Causes:

Acute Interstitial Nephritis (AIN): Allergic/inflammatory reaction causing interstitial inflammation

- Medications (antibiotics, NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors, allopurinol)

- Infections (pyelonephritis, viral infections)

- Autoimmune diseases

Glomerulonephritis: Inflammatory glomerular damage

- Post-infectious glomerulonephritis

- Lupus nephritis

- ANCA-associated vasculitis

- Anti-GBM disease (Goodpasture syndrome)

Vascular Causes:

- Renal artery thrombosis or embolism

- Renal vein thrombosis

- Malignant hypertension

- Thrombotic microangiopathy (HUS, TTP)

Intrinsic AKI shows impaired tubular function with inability to concentrate urine, resulting in higher urine sodium in AKI (>40 mEq/L) and urinary sediment abnormalities—muddy brown granular casts in ATN, white blood cell casts in AIN, red blood cell casts in glomerulonephritis.

Post-Renal AKI: Obstructive Uropathy

Mechanism: Post-renal AKI occurs when bilateral urinary tract obstruction (or unilateral in a single functioning kidney) causes retrograde pressure transmission to the kidneys, representing only 5-10% of AKI cases.

Pathophysiology:

- Obstruction increases intratubular pressure

- Backpressure reduces glomerular filtration pressure gradient

- Reflex renal vasoconstriction from increased pelvic pressure

- If prolonged >24-48 hours → Tubular injury from increased pressure

- Complete obstruction → Irreversible damage after 1-2 weeks

Common Causes:

Upper Urinary Tract (Bilateral or Solitary Kidney):

- Nephrolithiasis (kidney stones)

- Blood clots

- Papillary necrosis

- Retroperitoneal fibrosis

- Extrinsic compression (tumors, lymphadenopathy)

Lower Urinary Tract:

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) – most common in elderly men

- Prostate cancer

- Bladder cancer

- Neurogenic bladder (spinal cord injury, diabetes)

- Bladder outlet obstruction

- Urethral stricture

Post-renal AKI often presents with fluctuating urine output (anuria alternating with polyuria), bladder distention, and flank pain. Early relief of obstruction within 48 hours typically results in complete recovery, though prolonged obstruction may cause irreversible fibrosis.

AKI Diagnosis: Step-by-Step Clinical Approach

Initial Assessment & History

Proper AKI diagnosis begins with systematic evaluation combining clinical history, physical examination, and targeted laboratory investigations :

Key Historical Elements:

- Recent surgeries, procedures, or hospitalizations

- Medication history (NSAIDs, antibiotics, ACE inhibitors, diuretics, contrast exposure)

- Volume status (fluid intake, losses from vomiting/diarrhea, bleeding)

- Cardiac history (heart failure exacerbations)

- Urinary symptoms (oliguria, dysuria, hematuria, obstruction)

- Systemic illness (infection, sepsis, rhabdomyolysis)

- Chronic conditions (diabetes, liver disease, autoimmune disorders)

Physical Examination:

- Vital signs: Hypotension suggests pre-renal; hypertension may indicate glomerulonephritis

- Volume status: Orthostatic changes, skin turgor, mucous membranes, jugular venous pressure

- Cardiac exam: Heart failure signs (S3 gallop, pulmonary edema)

- Abdominal exam: Bladder distention, flank tenderness, palpable kidneys

- Skin: Rash (drug allergy, vasculitis), livedo reticularis (atheroemboli)

Laboratory Investigations

Essential Initial Tests:

- Serum Creatinine & BUN: Document baseline and trends to calculate creatinine rise in AKI and establish AKI stages

- Electrolytes: Check for hyperkalemia (>5.5 mEq/L), metabolic acidosis, hyponatremia

- Complete Blood Count: Anemia (hemolysis, bleeding), thrombocytopenia (HUS/TTP), eosinophilia (AIN)

- Urinalysis with Microscopy: Critical for differentiating causes (see below)

- Urine Electrolytes: Calculate FENa and FEUrea to distinguish pre-renal from ATN

Urinalysis Findings:

| Finding | Significance |

|---|---|

| Specific gravity >1.020 | Pre-renal (concentrated urine) |

| Specific gravity ~1.010 | ATN (isosthenuric, dilute) |

| Muddy brown granular casts | ATN (pathognomonic) |

| Red blood cell casts | Glomerulonephritis |

| White blood cell casts | Acute interstitial nephritis, pyelonephritis |

| Eosinophils (special stain) | Allergic interstitial nephritis |

| Protein 3-4+ | Glomerular disease |

| Hematuria | Glomerulonephritis, stones, tumor |

| Pyuria | Infection, interstitial nephritis |

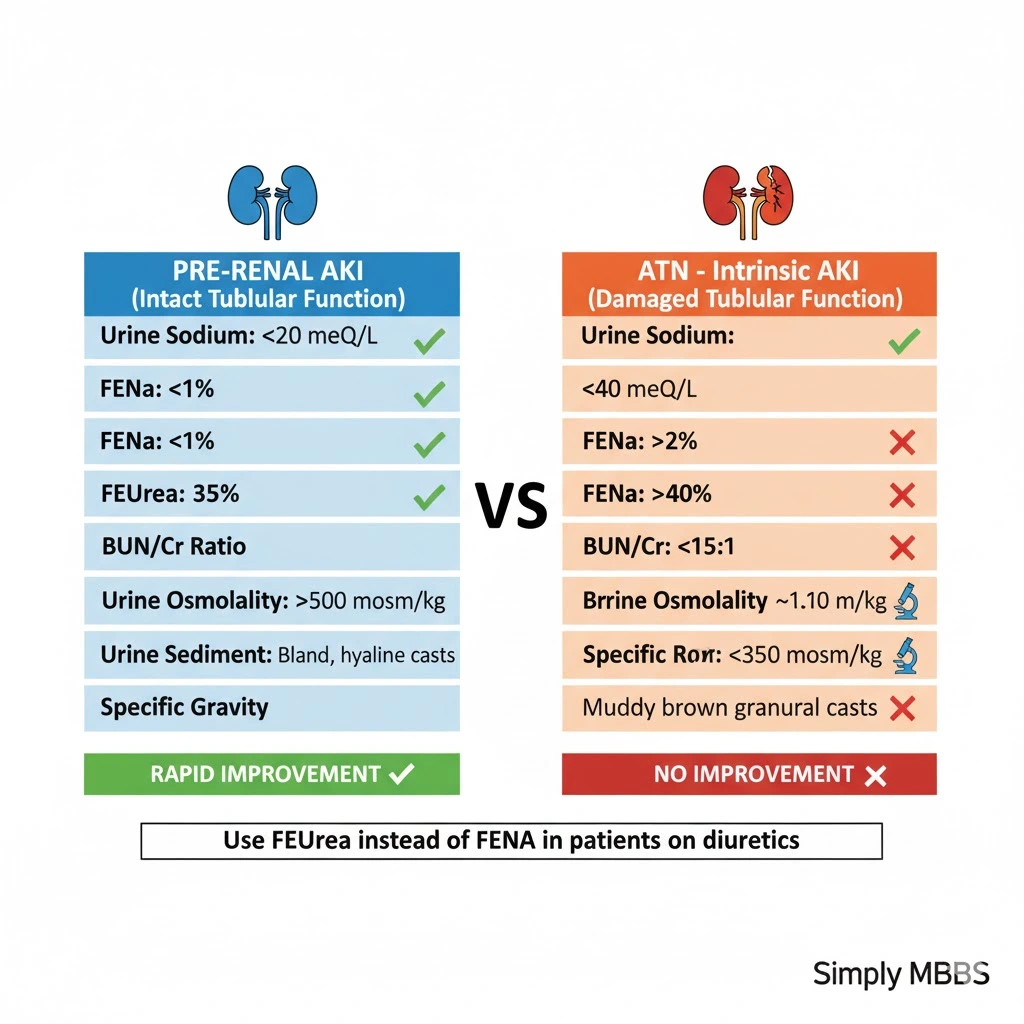

Urine Indices: Differentiating Pre-Renal from ATN

Urine indices in AKI provide invaluable diagnostic clues by assessing kidney tubular function :

Fractional Excretion of Sodium (FENa):

Formula: FENa = (Urine Na × Serum Cr) / (Serum Na × Urine Cr) × 100

Interpretation:

- FENa <1%: Pre-renal (kidneys avidly retaining sodium)

- FENa >2%: ATN (damaged tubules cannot reabsorb sodium)

- FENa 1-2%: Intermediate/unclear

Limitations: Diuretic therapy falsely elevates FENa, making interpretation unreliable in patients receiving furosemide or other diuretics.

Fractional Excretion of Urea (FEUrea):

Formula: FEUrea = (Urine Urea × Serum Cr) / (Serum Urea × Urine Cr) × 100

Interpretation:

- FEUrea <35-40%: Pre-renal

- FEUrea >40%: ATN

Advantage: Unlike sodium, urea excretion remains relatively unaffected by diuretics, making FEUrea superior for patients on diuretic therapy, particularly those with heart failure or cirrhosis. Studies show FEUrea has 85% sensitivity and 92% specificity for differentiating pre-renal from intrinsic AKI.

BUN/Creatinine Ratio:

Normal BUN/creatinine ratio ranges 10-20:1 :

- >20:1: Pre-renal (increased urea reabsorption with water)

- <10-15:1: ATN or intrinsic kidney disease

- 10-20:1: Normal or post-renal

Additional factors elevating BUN disproportionately: GI bleeding, steroid use, high protein intake, catabolic states.

Comprehensive Differentiation Table:

| Parameter | Pre-Renal | ATN (Intrinsic) |

|---|---|---|

| Urine Sodium (mEq/L) | <20 | >40 |

| FENa (%) | <1 | >2 |

| FEUrea (%) | <35 | >40 |

| Urine Osmolality (mOsm/kg) | >500 | <350 |

| Urine/Plasma Osmolality | >1.5 | <1.1 |

| BUN/Cr Ratio | >20:1 | <10-15:1 |

| Urine Specific Gravity | >1.020 | ~1.010 |

| Urine Sediment | Bland, hyaline casts | Muddy brown granular casts, tubular epithelial cells |

| Response to Fluid Challenge | Rapid improvement | No improvement |

Imaging Studies

Renal Ultrasound: First-line imaging for all AKI patients to assess :

- Kidney size (small suggests chronic disease; large suggests infiltration, obstruction)

- Hydronephrosis (indicates post-renal obstruction)

- Bladder distention

- Kidney stones, masses, cysts

Additional Imaging When Indicated:

- CT Scan: Better visualization of stones, masses, vascular lesions

- Doppler Ultrasound: Renal artery stenosis, thrombosis evaluation

- MR Angiography: Renal vascular imaging without nephrotoxic contrast

Diagnostic Flowchart Approach

Step 1: Confirm AKI using KDIGO criteria (creatinine rise, oliguria)

2: Categorize as Pre-renal, Intrinsic, or Post-renal based on:

-

Clinical context (volume status, medications, symptoms)

-

Urinalysis findings

-

Urine indices (FENa, FEUrea, BUN/creatinine ratio)

-

Renal ultrasound (hydronephrosis)

3: Identify specific etiology within category:

-

Pre-renal: Volume depletion vs cardiac vs sepsis vs drugs

-

Intrinsic: ATN vs AIN vs glomerulonephritis vs vascular

-

Post-renal: BPH vs stones vs cancer vs neurogenic

4: Stage severity using AKI stages (KDIGO)

5: Initiate targeted therapy and monitoring

Acute Kidney Injury Management: Evidence-Based Treatment Strategies

General Principles

Modern AKI management focuses on three fundamental pillars :

- Identify and treat underlying cause (reverse pre-renal factors, remove nephrotoxins, relieve obstruction)

- Prevent progression (optimize hemodynamics, avoid additional injury)

- Supportive care (fluid-electrolyte management, nutrition, RRT if needed)

Pre-Renal AKI Management

Fluid Resuscitation:

The cornerstone of pre-renal AKI treatment involves restoring adequate renal perfusion through intravenous fluid therapy :

Fluid Type Selection:

- Balanced Crystalloids (Preferred): Lactated Ringer’s, Plasma-Lyte, Hartmann’s solution show superior outcomes compared to 0.9% saline

- 0.9% Normal Saline: Causes hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis; avoid unless specific indication (e.g., hypochloremic alkalosis)

- Colloids (Albumin, Starches): Generally avoided; no clear benefit over crystalloids and potential harm from synthetic starches

Research from the SPLIT trial and other large studies demonstrates that balanced crystalloids are preferred over 0.9% sodium chloride for fluid resuscitation in both critically ill and non-critically ill patients. Balanced solutions more closely match plasma electrolyte composition, minimizing acid-base disturbances.

Fluid Administration Strategy:

- Initial Bolus: 500-1000 mL crystalloid over 30-60 minutes

- Reassess: Check blood pressure, heart rate, urine output, volume status

- Fluid Challenge Test: If response adequate (BP improvement, urine output increase) → Continue fluid replacement guided by clinical endpoints

- If No Response: Consider alternative diagnosis (ATN, cardiac dysfunction) or vasopressor support in distributive shock

Hemodynamic Optimization:

- Septic Shock: Early goal-directed therapy with fluids + vasopressors (norepinephrine first-line)

- Cardiogenic Shock: Inotropic support (dobutamine), consider mechanical circulatory support

- Medication Review: Discontinue NSAIDs, ACE inhibitors/ARBs temporarily until kidney function stabilizes

Intrinsic AKI Management

Acute Tubular Necrosis (ATN):

Unfortunately, no specific pharmacologic therapy exists to reverse established ATN. Management remains primarily supportive:

Supportive Measures:

- Optimize Hemodynamics: Maintain mean arterial pressure >65 mmHg

- Discontinue Nephrotoxins: Stop or adjust aminoglycosides, NSAIDs, contrast agents, vancomycin

- Adjust Drug Dosing: Renally cleared medications require dose reduction

- Avoid Fluid Overload: Judicious fluid management; diuretics if volume overloaded (furosemide 40-80 mg IV)

- Nutritional Support: Adequate protein (0.8-1.0 g/kg/day), avoid hypercatabolism

- Monitor Complications: Daily electrolytes (watch hyperkalemia), acid-base status, fluid balance

Diuretic Use: Loop diuretics (furosemide) can convert oliguric to non-oliguric AKI, improving fluid management, but do NOT improve kidney recovery, reduce dialysis need, or decrease mortality. Use only for symptom management of volume overload, not to “treat” AKI itself.

Acute Interstitial Nephritis:

- Discontinue offending drug immediately

- Consider corticosteroids for severe cases (controversial, limited evidence)

- Most cases improve with drug withdrawal alone over 1-3 weeks

Glomerulonephritis:

- Requires specific immunosuppressive therapy based on type

- High-dose corticosteroids

- Cyclophosphamide, rituximab, or other agents

- Plasmapheresis for rapidly progressive disease

- Requires nephrology consultation

Post-Renal AKI Management

Urgent Obstruction Relief:

Post-renal AKI management centers on prompt decompression :

Lower Tract Obstruction:

- Urethral catheterization (Foley catheter)

- Suprapubic catheter if urethral placement impossible

- Transurethral resection of prostate (TURP) for BPH

Upper Tract Obstruction:

- Percutaneous nephrostomy tubes

- Retrograde ureteral stents

- Lithotripsy or surgical stone removal

Post-Obstruction Diuresis: Following relief of prolonged bilateral obstruction, massive diuresis may occur (up to 10-15 L/day) due to:

- Osmotic diuresis from retained urea

- Tubular dysfunction

- Natriuresis

Management: Replace 50-75% of urine output with 0.45% saline; monitor electrolytes closely for hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia.

Renal Replacement Therapy (Dialysis)

Indications for Emergency Dialysis (Mnemonic: AEIOU):

- Acidosis (severe metabolic acidosis pH <7.1 unresponsive to therapy)

- Electrolyte abnormalities (hyperkalemia >6.5 mEq/L with ECG changes)

- Ingestions (toxins like methanol, ethylene glycol, lithium, salicylates)

- Overload (pulmonary edema refractory to diuretics)

- Uremia (encephalopathy, pericarditis, bleeding)

Modality Selection:

- Intermittent Hemodialysis (IHD): Standard for stable patients

- Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy (CRRT): Preferred for hemodynamically unstable ICU patients; gentler fluid removal

- Peritoneal Dialysis: Rarely used for acute settings

Timing Controversy: Recent evidence suggests early initiation of RRT (within 12 hours of Stage 2-3 AKI) does NOT improve mortality compared to delayed strategy (initiating only for absolute indications). Current recommendation: Avoid unnecessary early dialysis; wait for clear indications unless severe complications present.

Prevention Strategies

High-Risk Situations Requiring Preventive Measures:

- Contrast-enhanced imaging procedures

- Major surgery (cardiac, vascular)

- Sepsis/critical illness

- Nephrotoxic drug administration

Evidence-Based Prevention:

- Volume Expansion: IV isotonic crystalloids before/during high-risk procedures

- Medication Review: Hold ACE inhibitors, ARBs, NSAIDs, metformin perioperatively

- Minimize Contrast: Use lowest possible dose; consider alternative imaging

- Avoid Nephrotoxins: Select non-nephrotoxic alternatives when possible

- Biomarker Monitoring: Serial creatinine checks in high-risk patients

For patients with chronic conditions like pneumonia and sepsis-related AKI or those recovering from plasma proteins and kidney function abnormalities, close monitoring becomes essential for early intervention.

Common Mistakes to Avoid in Acute Kidney Injury Care

- Delayed Recognition: Missing early Stage 1 AKI by not trending creatinine patterns; even small rises matter

- Using FENa in Diuretic-Treated Patients: Diuretics invalidate FENa; always use FEUrea instead

- Inappropriate Fluid Resuscitation: Continuing aggressive fluids in established ATN or volume-overloaded states worsens outcomes

- Normal Saline Overuse: Exclusive use of 0.9% saline causes hyperchloremic acidosis; prefer balanced crystalloids

- Missing Post-Renal Obstruction: Not ordering renal ultrasound in all AKI cases

- Continuing Nephrotoxic Drugs: Failing to stop or adjust NSAIDs, aminoglycosides, ACE inhibitors during acute phase

- Drug Dosing Errors: Not adjusting renally cleared medications (antibiotics, anticoagulants) for reduced GFR

- Over-Reliance on Diuretics: Using furosemide to “treat” AKI rather than just manage volume; diuretics don’t improve kidney recovery

- Premature Dialysis Initiation: Starting RRT without clear indications increases complications without benefit

- Inadequate Follow-Up: Discharging recovering AKI patients without outpatient nephrology referral and kidney function monitoring

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) About Acute Kidney Injury

Q : What is the difference between acute kidney injury and chronic kidney disease?

A : Acute Kidney Injury occurs suddenly over hours to days with potential for complete recovery, while chronic kidney disease develops gradually over months to years with irreversible damage. AKI represents a medical emergency requiring immediate intervention, whereas CKD needs long-term management and may eventually progress to kidney failure requiring dialysis or transplantation. However, episodes of AKI significantly increase the risk of later developing CKD, creating an important connection between these conditions.

Q : Can acute kidney injury be reversed?

A : Yes, most cases of Acute Kidney Injury can be reversed if diagnosed early and the underlying cause is addressed promptly. Pre-renal AKI typically resolves within 24-48 hours after restoring kidney blood flow through fluid resuscitation. Even intrinsic AKI like acute tubular necrosis shows recovery in 60-70% of patients over 7-21 days as tubular epithelial cells regenerate. However, severe Stage 3 AKI requiring dialysis or cases with prolonged ischemia may result in permanent kidney damage and chronic kidney disease.

Q : When should I use FEUrea instead of FENa in AKI diagnosis?

A : You should use FEUrea instead of FENa whenever the patient is receiving diuretic therapy (furosemide, hydrochlorothiazide) or has conditions like heart failure or cirrhosis. Diuretics artificially increase urinary sodium excretion, falsely elevating FENa above 1% even in true pre-renal states, leading to misdiagnosis. FEUrea remains unaffected by diuretics because urea reabsorption occurs through passive mechanisms, making it more reliable with 85% sensitivity and 92% specificity for differentiating pre-renal from intrinsic AKI. The cutoff for FEUrea is <35-40% for pre-renal and >40% for ATN.

Q : How do I differentiate pre-renal AKI from acute tubular necrosis using urine indices?

A : The key distinguishing features using urine indices in AKI include :

Pre-renal (intact tubular function): Urine sodium <20 mEq/L, FENa <1%, FEUrea <35%, BUN/creatinine ratio >20:1, urine osmolality >500 mOsm/kg, urine specific gravity >1.020, bland urinary sediment with occasional hyaline casts, and rapid response to fluid challenge test showing improved urine output and creatinine.

ATN (damaged tubular function): Urine sodium >40 mEq/L, FENa >2%, FEUrea >40%, BUN/creatinine ratio <15:1, urine osmolality <350 mOsm/kg (isosthenuric), urine specific gravity ~1.010, muddy brown granular casts and tubular epithelial cells in sediment, and no response to fluid administration.

Exam Questions & Answers: University Pattern

Question 1: Short Answer (10 Marks)

Q: Define Acute Kidney Injury according to KDIGO criteria and explain its three-stage classification system. Compare RIFLE, AKIN, and KDIGO criteria highlighting key differences.

Model Answer (Bullet Points):

Definition:

- Acute Kidney Injury: Abrupt decrease in kidney function within 48 hours to 7 days

- Diagnosed by ANY of: Serum creatinine ↑ ≥0.3 mg/dL within 48h, OR creatinine ≥1.5× baseline within 7 days, OR urine output <0.5 mL/kg/h for 6h

KDIGO Three-Stage Classification:

- Stage 1: Creatinine 1.5-1.9× baseline OR ≥0.3 mg/dL rise OR UO <0.5 mL/kg/h × 6-12h

- Stage 2: Creatinine 2.0-2.9× baseline OR UO <0.5 mL/kg/h × ≥12h

- Stage 3: Creatinine ≥3.0× baseline OR ≥4.0 mg/dL OR initiation RRT OR UO <0.3 mL/kg/h × ≥24h or anuria ×12h

Comparison Table:

| Criteria | RIFLE (2004) | AKIN (2007) | KDIGO (2012) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stages | 5 (Risk, Injury, Failure, Loss, ESRD) | 3 | 3 |

| Time window | 7 days | 48 hours | 48h + 7 days combined |

| Minimum ↑ | 1.5× baseline | 0.3 mg/dL or 1.5× | 0.3 mg/dL or 1.5× |

| GFR criteria | Yes | No | No |

| Sensitivity Stage 1 | Lower | Higher | Highest |

Key Differences:

- RIFLE includes GFR-based criteria and outcome categories (Loss/ESRD); others focus only on acute phase

- AKIN introduced 0.3 mg/dL absolute rise criterion for early detection

- KDIGO unified best elements: combines 48h timeframe (AKIN) with 7-day window (RIFLE)

Mark Distribution: Definition (2), Staging (3), Comparison table (3), Key differences (2)

Question 2: Long Answer (20 Marks)

Q: A 65-year-old diabetic male presents with 3 days of vomiting and diarrhea. BP 90/60 mmHg, HR 110/min. Labs show: Creatinine 3.2 mg/dL (baseline 1.0 mg/dL), BUN 60 mg/dL, Na 136 mEq/L, K 5.8 mEq/L. Urine: Na 12 mEq/L, osmolality 520 mOsm/kg, no casts. Discuss: (a) Classification and staging of AKI (b) Differentiate pre-renal vs ATN (c) Management approach

Model Answer:

a) Classification & Staging (6 marks):

Acute Kidney Injury Classification:

- Type: Pre-renal AKI (hypoperfusion from volume depletion)

- Evidence: Clinical context (GI losses), hypotension, tachycardia, elevated BUN/creatinine ratio (60:3.2 = 18.75:1, approaching >20:1), low urine sodium (12 mEq/L), concentrated urine (520 mOsm/kg)

Staging per KDIGO:

- Baseline Cr 1.0 → Current 3.2 mg/dL = 3.2× baseline increase

- Stage 3 AKI (creatinine >3.0× baseline)

- High-risk category requiring intensive monitoring

b) Differentiation Pre-renal vs ATN (8 marks):

Favors Pre-renal AKI:

| Parameter | Patient Value | Pre-renal Expected | ATN Expected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urine sodium | 12 mEq/L | <20 | >40 |

| BUN/Cr ratio | 18.75:1 | >20:1 | <15:1 |

| Urine osmolality | 520 mOsm/kg | >500 | <350 |

| Urine sediment | No casts | Bland/hyaline | Muddy brown granular casts |

FENa Calculation (if available):

- FENa = (Urine Na × Serum Cr) / (Serum Na × Urine Cr) × 100

- Expected <1% for pre-renal

Clinical Context Supporting Pre-renal:

- Clear precipitating cause (GI losses)

- Appropriate physiologic response (concentrated urine, sodium retention)

- Intact tubular function

- Expected rapid reversal with fluid resuscitation

c) Management Approach (6 marks):

Immediate Management:

-

Fluid Resuscitation:

-

Balanced crystalloids (Lactated Ringer’s or Plasma-Lyte) 500-1000 mL bolus over 30-60 min

-

Reassess hemodynamics and urine output

-

Continue fluid replacement guided by clinical response

-

Target MAP >65 mmHg, improved UO

-

-

Electrolyte Management:

-

Hyperkalemia (5.8 mEq/L): ECG monitoring, if >6.0 or ECG changes → IV calcium gluconate (cardiac protection), insulin + dextrose, sodium bicarbonate if acidotic, consider dialysis if >6.5 with ECG changes

-

-

Discontinue Nephrotoxins:

-

Hold ACE inhibitors/ARBs, NSAIDs, metformin

-

Review all medications for renal dosing adjustments

-

-

Monitor Response:

-

Repeat creatinine at 24-48 hours

-

Hourly urine output measurement

-

Daily electrolytes

-

Fluid challenge test: Successful if creatinine improves, UO increases

-

-

Nephrology Consultation if:

-

No improvement after adequate fluid resuscitation (suggests ATN)

-

Persistent hyperkalemia

-

Development of dialysis indications (AEIOU)

-

Expected Outcome: Pre-renal AKI should show creatinine improvement within 24-48 hours if adequate perfusion restored

Question 3: Viva Voce Questions

Q1: What is the oliguria definition according to KDIGO?

A: Urine output <0.5 mL/kg/hour for 6 hours

Q2: When should you use FEUrea instead of FENa?

A: In patients receiving diuretics, or those with heart failure/cirrhosis where FENa becomes unreliable

Q3: What urinary finding is pathognomonic for ATN?

A: Muddy brown granular casts and tubular epithelial cells

Q4: Name three absolute indications for emergency dialysis?

A: Severe hyperkalemia (>6.5 mEq/L with ECG changes), refractory pulmonary edema, severe acidosis (pH <7.1)

Q5: Why are balanced crystalloids preferred over normal saline?

A: Reduce hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis risk; more physiologic electrolyte composition

Quick Diagram Prompt for Exam Preparation

Flowchart: AKI Diagnostic Approach

Suspected AKI (↑Creatinine or ↓UO)

↓

Stage using KDIGO Criteria

↓

┌─────┴─────┐

Pre-renal Intrinsic Post-renal

↓ ↓ ↓

FENa <1% FENa >2% Hydronephrosis

UNa <20 UNa >40 on ultrasound

BUN/Cr>20 BUN/Cr<15 Bladder distention

Bland urine Granular casts

↓ ↓ ↓

Fluid Rx Supportive Relief obstruction

Viva Tips

- Always mention KDIGO as the current gold standard for AKI diagnosis

- Emphasize early detection (Stage 1) prevents progression

- Know urine indices cutoffs: FENa <1% (pre-renal), >2% (ATN);

Conclusion: Mastering AKI for Better Patient Outcomes

Acute Kidney Injury represents one of modern medicine’s most critical challenges—a condition affecting millions worldwide that demands rapid recognition, precise diagnosis, and immediate intervention. As we’ve explored throughout this comprehensive guide, understanding the distinction between pre-renal vs intrinsic vs post-renal AKI, mastering diagnostic urine indices, and implementing evidence-based AKI management protocols can literally mean the difference between complete recovery and permanent kidney damage.

The evolution from RIFLE to AKIN to the current KDIGO criteria for AKI has revolutionized early detection, enabling clinicians to identify Stage 1 AKI before irreversible damage occurs. Remember that even mild elevations in creatinine rise carry significant implications—patients who survive AKI face a 13-fold increased risk of developing chronic kidney disease and substantially elevated cardiovascular mortality. This underscores why prevention, early recognition using oliguria monitoring and AKI stages (KDIGO), and aggressive supportive care remain paramount.

Whether you’re an MBBS student preparing for university examinations, a healthcare professional managing critically ill patients, or someone concerned about kidney health, the principles outlined here—from calculating FENa vs FEUrea to choosing balanced crystalloids over normal saline—provide the foundation for excellence in nephrology care.

Key Takeaways to Remember:

- Early detection saves kidneys: Stage 1 AKI is reversible with prompt intervention

- Urine indices differentiate causes: Use FEUrea in diuretic-treated patients, not FENa

- KDIGO is the gold standard for diagnosis and staging worldwide

- Treatment targets the cause: Fluids for pre-renal, obstruction relief for post-renal, supportive care for intrinsic

- Long-term follow-up matters: All AKI survivors need nephrology monitoring at 3 months

Stay Updated & Informed

At SimplyMBBS, we’re committed to making complex medical concepts accessible to students, healthcare professionals, and curious readers worldwide. Don’t miss our upcoming articles on related topics like chronic kidney disease progression, diabetic nephropathy, and electrolyte disorders—subscribe to our newsletter at simplymbbs.com to receive evidence-based medical content directly to your inbox.