Introduction To Pneumonia

Every year, pneumonia affects millions of people worldwide, causing significant morbidity and mortality across all age groups. For medical students preparing for MBBS exams, understanding pneumonia: clinical approach, diagnosis & management for MBBS is not just academically important—it’s a critical skill that will define your clinical competence as a future physician. Whether you’re a student cramming for your medicine finals, a doctor seeking a quick clinical refresher, or someone trying to understand this common yet potentially serious infection, this comprehensive guide will walk you through everything you need to know about pneumonia, from its pathophysiology to its management.

Pneumonia stands as one of the leading causes of infectious disease-related deaths globally, particularly affecting vulnerable populations including children under five, elderly individuals, and immunocompromised patients. In the United States alone, approximately 1 million adults are hospitalized with pneumonia annually, with around 50,000 deaths reported each year. The clinical approach to pneumonia has evolved significantly with the 2019 American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America (ATS/IDSA) guidelines providing updated evidence-based recommendations for diagnosis and management.

What is Pneumonia: Clinical Approach, Diagnosis & Management for MBBS?

Medical Definition from Standard Textbooks

According to Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine and Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine—two standard medical textbooks followed worldwide—pneumonia is defined as an acute infection of the pulmonary parenchyma characterized by inflammation of the alveolar spaces, typically caused by microorganisms including bacteria, viruses, fungi, or parasites.

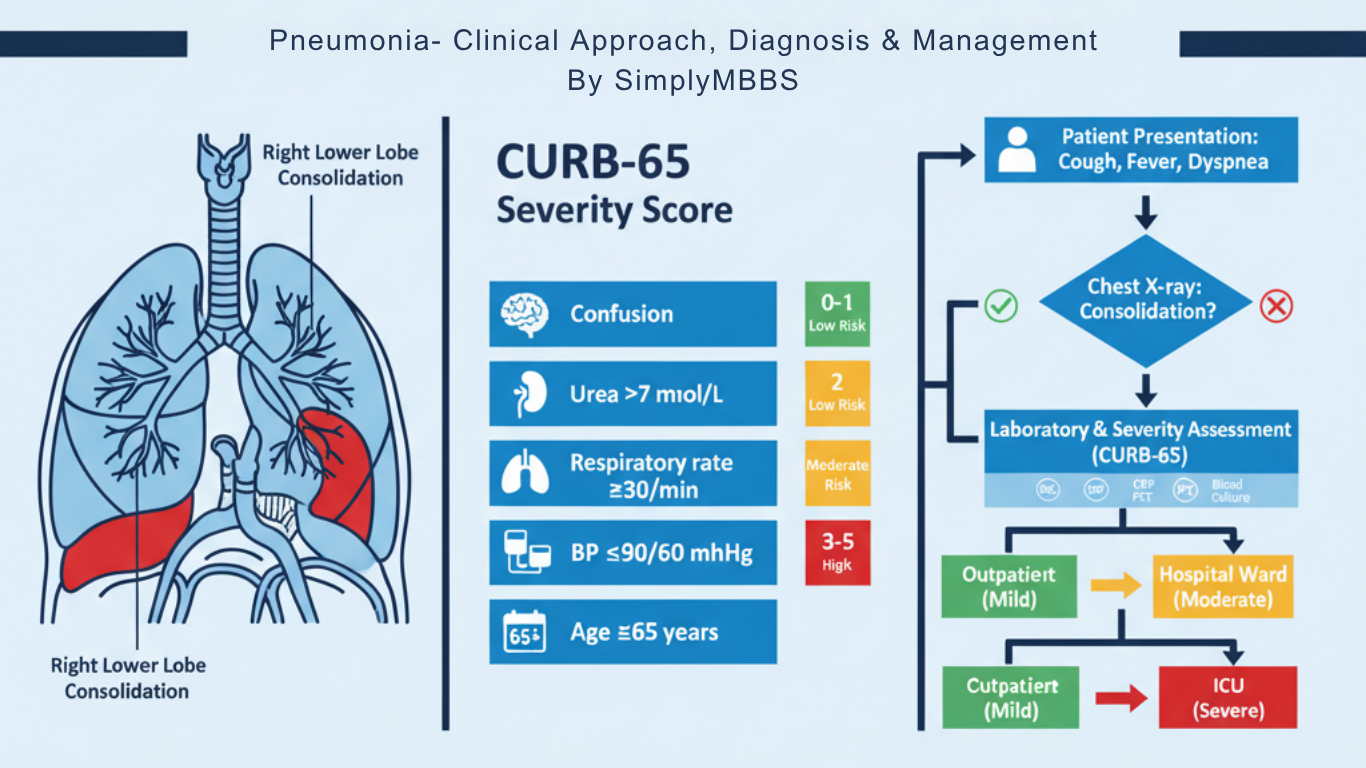

The clinical hallmark of pneumonia involves the presence of new pulmonary infiltrates on chest imaging (chest X-ray or CT scan) accompanied by signs and symptoms of lower respiratory tract infection, including cough, sputum production, dyspnea, fever, and pleuritic chest pain. The 2019 ATS/IDSA guidelines recommend diagnosing community-acquired pneumonia based on the presence of a radiographic infiltrate, at least one respiratory symptom, and another clinical finding consistent with acute infection.

The pathological process involves the filling of alveolar spaces with inflammatory exudate composed of neutrophils, fibrin, and fluid, leading to consolidation visible on imaging studies. This consolidation impairs gas exchange, resulting in hypoxemia and the characteristic clinical presentation of pneumonia.

Why Understanding Pneumonia Matters for MBBS Students and Doctors

Global Impact and Burden

Pneumonia remains a leading cause of death worldwide, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. The World Health Organization reports that pneumonia accounts for approximately 15% of all deaths in children under five years old globally. In adults, particularly those over 65 years of age, pneumonia is the most common cause of infection-related hospitalization and death.

Understanding pneumonia diagnosis and management is crucial because:

The disease affects diverse patient populations with varying severity, from mild outpatient cases to severe intensive care unit admissions requiring mechanical ventilation. The mortality rate varies significantly based on severity, with CURB-65 scores of 0-1 associated with less than 3% mortality, while scores of 4-5 carry a 27.8% mortality risk. Immunocompromised patients, including those with diabetes mellitus, are at 2-4 times higher risk of developing pneumonia compared to healthy individuals.

Clinical Relevance in Medical Practice

For MBBS students and practicing physicians, mastering pneumonia: clinical approach, diagnosis & management is essential because you will encounter pneumonia cases throughout your medical career across multiple specialties—internal medicine, emergency medicine, pediatrics, and critical care. The ability to rapidly assess severity, identify causative pathogens, initiate appropriate empiric antibiotic therapy, and recognize treatment failures can be life-saving.

Furthermore, the emergence of antibiotic-resistant pathogens, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa, has made appropriate antibiotic stewardship and guideline-based management more important than ever.

Types of Pneumonia: Classification and Key Differences

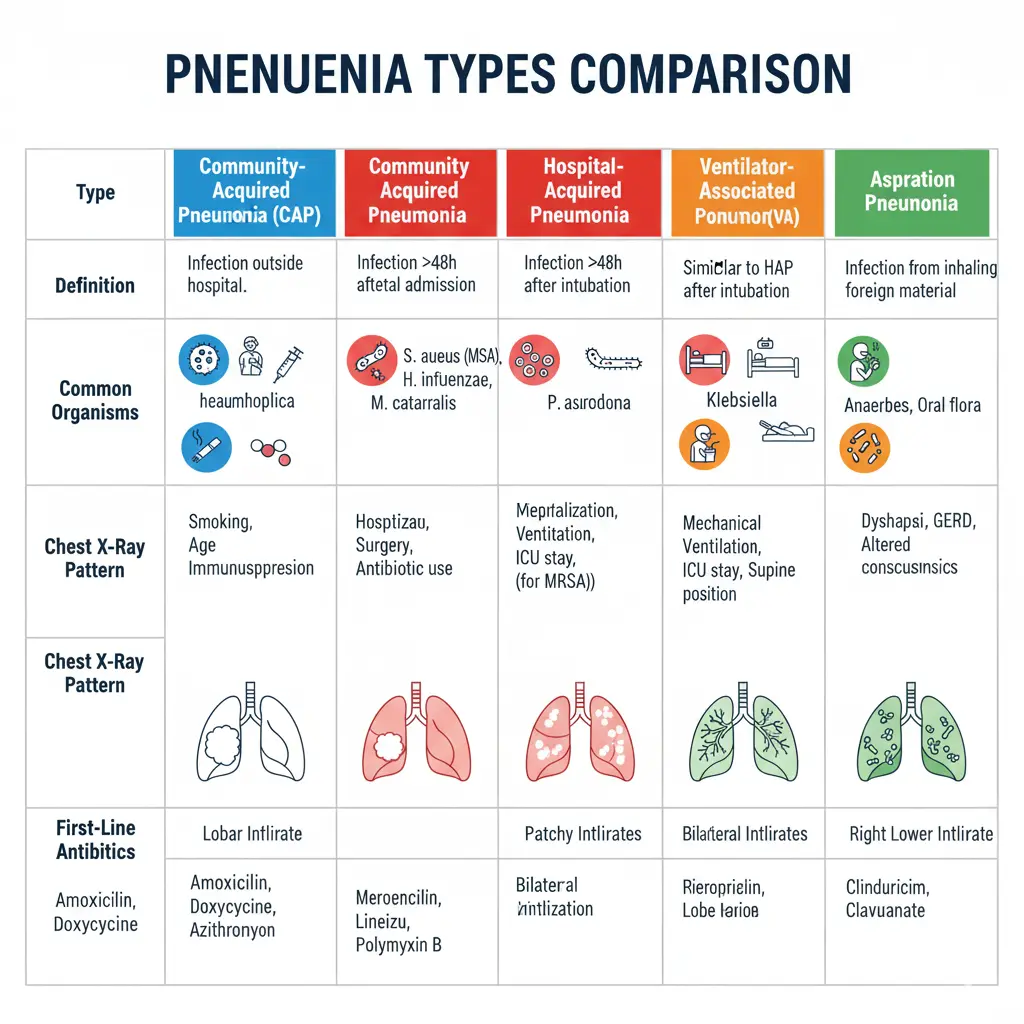

Community-Acquired Pneumonia (CAP)

Community-acquired pneumonia is defined as pneumonia that develops in individuals who have not been recently hospitalized (within 14 days) or had recent healthcare facility exposure. CAP is the most common type of pneumonia, with an annual incidence of 1.6 to 13.4 cases per 1,000 inhabitants in adults.

Key characteristics of CAP:

Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) remains the most common causative pathogen, accounting for 20-30% of cases. Other typical pathogens include Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and Staphylococcus aureus. Atypical organisms such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Legionella pneumophila account for 15-40% of CAP cases. Viral pathogens, including influenza, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and coronaviruses, are increasingly recognized causes.

The prognosis of CAP depends on patient age, comorbidities, and severity at presentation, with hospital mortality ranging from less than 1% in low-risk outpatients to over 20% in severe cases requiring ICU admission.

Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia (HAP)

Hospital-acquired pneumonia is defined as pneumonia that develops 48 hours or more after hospital admission in a patient who was not intubated at the time of admission. HAP accounts for approximately 0.5-2% of all hospital admissions and is associated with higher mortality rates (20-50%) compared to CAP.

Critical differences between HAP and CAP:

HAP is more likely to be caused by multidrug-resistant organisms, including MRSA (24.6% of culture-positive cases), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (18.8%), and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing gram-negative bacteria. Patients with HAP have higher rates of inappropriate initial antibiotic therapy (28.3% vs 13% in CAP), which is an independent risk factor for mortality. The hospital mortality rate is significantly higher in HAP (24.6%) compared to CAP (9.1%).

Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia (VAP)

Ventilator-associated pneumonia occurs 48 hours or more after endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. VAP is one of the most common nosocomial infections in intensive care units, with incidence rates of 10-25% in mechanically ventilated patients.

The pathogenesis of VAP involves aspiration of colonized oropharyngeal secretions around the endotracheal tube cuff, with causative organisms typically including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, MRSA, Acinetobacter baumannii, and other hospital-acquired pathogens.

Aspiration Pneumonia

Aspiration pneumonia results from inhalation of oropharyngeal or gastric contents into the lower respiratory tract. This type occurs most commonly in patients with impaired consciousness, dysphagia, or diminished gag reflex, including those with stroke, seizures, alcohol intoxication, or neuromuscular disorders.

Aspiration pneumonia typically involves anaerobic bacteria from the oral cavity and may present with putrid sputum, necrotizing pneumonia, or lung abscess formation. The mortality rate can be as high as 70% depending on the volume and nature of aspirated material.

Pathophysiology: How Pneumonia Develops

Mechanism of Infection

The lungs maintain a delicate balance between microbial exposure and host defense mechanisms. Under normal circumstances, the lower respiratory tract contains a diverse microbiome with species including Streptococcus spp. and Mycoplasma spp. that are held in check by pulmonary host defenses.

Pneumonia develops when this balance is disrupted through one of several routes:

Microaspiration is the most common route, where small amounts of oropharyngeal secretions containing pathogenic organisms are inhaled into the lower airways. This occurs regularly even in healthy individuals during sleep, but effective mucociliary clearance and immune responses prevent infection. Inhalation of aerosolized infectious particles occurs with pathogens like Legionella pneumophila, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and respiratory viruses that can be transmitted through respiratory droplets. Hematogenous spread from distant infection sites is less common but can occur with Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia causing septic emboli to the lungs. Direct extension from contiguous structures, such as in empyema or subphrenic abscess, represents another uncommon route.

Immune Response and Inflammation

Once pathogenic microorganisms reach the alveolar space, they trigger a cascade of immune responses. The innate immune system recognizes pathogen-associated molecular patterns through toll-like receptors on alveolar macrophages and epithelial cells, initiating cytokine production including interleukin-1 (IL-1), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α).

These pro-inflammatory cytokines recruit neutrophils to the infected alveoli, creating the characteristic inflammatory exudate. In bacterial pneumonia, neutrophils predominate, while viral pneumonia typically shows lymphocytic infiltration, and fungal or mycobacterial pneumonia demonstrates granulomatous inflammation.

The alveolar filling with inflammatory cells, fibrin, and fluid produces the radiographic pattern of consolidation seen on chest X-rays. This consolidation impairs gas exchange, leading to ventilation-perfusion mismatch and hypoxemia, which manifests clinically as dyspnea and decreased oxygen saturation.

In patients with diabetes mellitus or other immunocompromising conditions, several mechanisms increase pneumonia risk. Hyperglycemia impairs neutrophil chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and bacterial killing. Chronic inflammation characteristic of diabetes disrupts both innate and adaptive immunity. Diabetic patients also have altered pulmonary capillary function and increased bacterial colonization of airways.

Clinical Presentation: Signs and Symptoms

Typical Pneumonia Symptoms

Typical bacterial pneumonia, particularly pneumococcal pneumonia, classically presents with acute onset of symptoms over hours to days. The characteristic clinical features include:

Fever is usually high-grade (>38.5°C or 101.3°F) with chills and rigors. Productive cough with purulent sputum that may be rust-colored in pneumococcal pneumonia or green in Pseudomonas infection. Pleuritic chest pain is sharp, localized pain that worsens with deep inspiration or coughing, indicating pleural involvement. Dyspnea or shortness of breath, with severity proportional to the extent of lung involvement and degree of hypoxemia. Systemic symptoms include malaise, myalgias, headache, and decreased appetite.

Physical examination findings in typical pneumonia may reveal:

Tachypnea (respiratory rate >20 breaths/minute) and tachycardia (pulse >100 beats/minute). Fever (temperature >38°C) present in approximately 70-80% of cases. Crackles (rales) are the most common auscultatory finding, heard as inspiratory sounds over the affected lung area. These have a positive likelihood ratio of 3.2 for diagnosing pneumonia. Bronchial breath sounds indicate consolidation and have a positive likelihood ratio of 3.3. Dullness to percussion over the consolidated area has a positive likelihood ratio of 5.7, making it one of the most valuable examination findings. Increased tactile fremitus and egophony may be present with significant consolidation.

However, it’s important to note that the traditional chest physical examination has limited sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing pneumonia, with studies showing sensitivity of only 47-69% and specificity of 58-75%. Therefore, chest radiography remains essential for diagnosis confirmation.

Atypical Pneumonia Presentation

Atypical pneumonia, caused by organisms such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Legionella pneumophila, typically presents with a more insidious onset and different clinical features.

Key characteristics of atypical pneumonia:

Gradual onset over days to weeks rather than acute presentation. Dry, non-productive cough is more common than purulent sputum production. Prominent extrapulmonary manifestations help distinguish atypical from typical pneumonia, including headache, myalgias, gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), skin rashes, and neurological symptoms. Mild respiratory symptoms despite sometimes impressive radiographic findings (“walking pneumonia”). Lower fever compared to typical bacterial pneumonia.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia often affects younger adults and may be associated with bullous myringitis, hemolytic anemia, and erythema multiforme. Legionella pneumonia typically causes severe disease with high fever, confusion, hyponatremia, elevated liver enzymes, and relatively lower pulse rate compared to the degree of fever. Chlamydia pneumoniae usually causes mild pneumonia with pharyngitis and hoarseness.

The distinction between typical and atypical pneumonia is clinically important because atypical pathogens lack cell walls (or reside intracellularly) and are therefore resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics, requiring macrolides, fluoroquinolones, or tetracyclines for effective treatment.

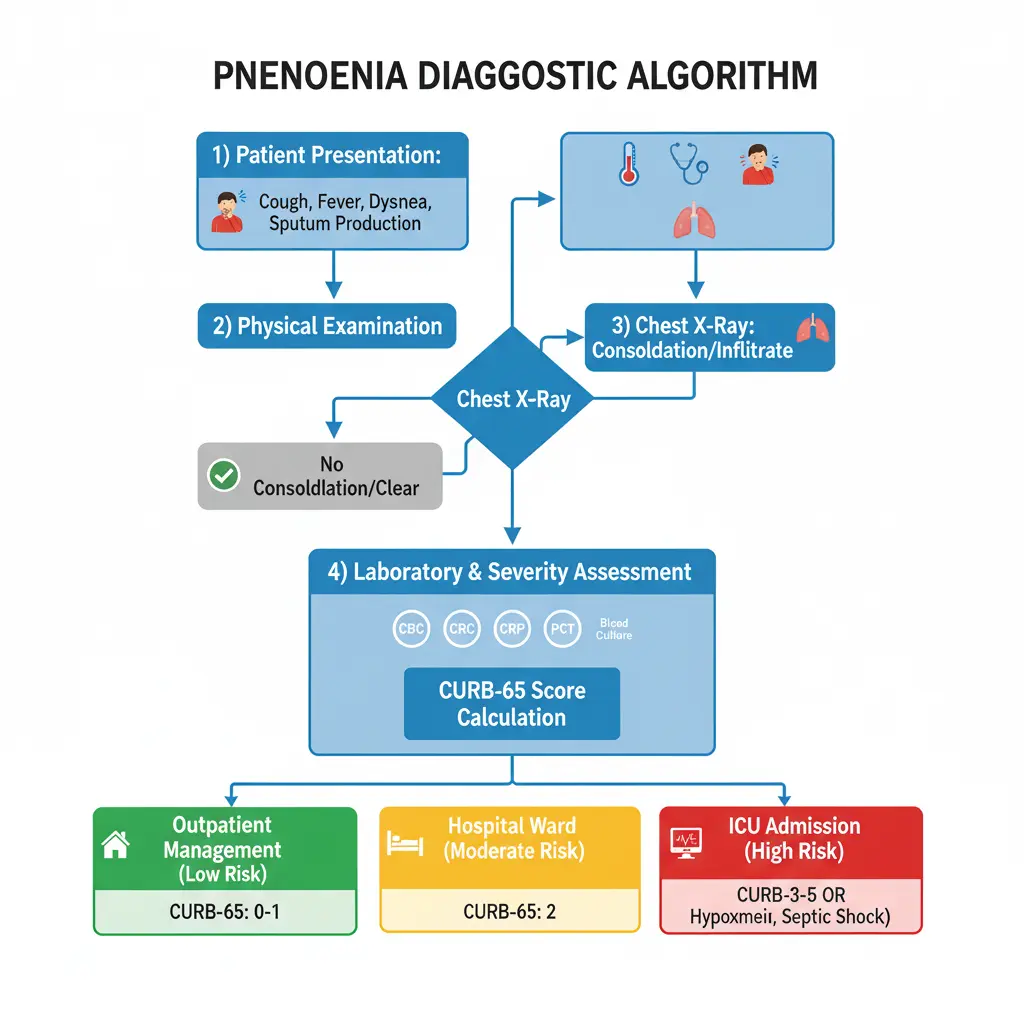

Diagnostic Approach: Step-by-Step Clinical Assessment

History Taking

A comprehensive history is the foundation of diagnosing pneumonia: clinical approach, diagnosis & management for MBBS practice. Essential elements include:

Symptom characterization: Duration, severity, and progression of cough, sputum production, dyspnea, and chest pain. Fever pattern: High-grade fever with rigors suggests bacterial infection, while gradual low-grade fever may indicate atypical or viral etiology. Risk factor assessment: Recent hospitalization or healthcare exposure (within 90 days), antibiotic use (within 3 months), residence in nursing home or long-term care facility, chronic lung disease (COPD, bronchiectasis), immunocompromising conditions (HIV, diabetes, cancer, immunosuppressive therapy), aspiration risk factors (dysphagia, altered consciousness, alcohol abuse), and recent travel or exposure history (tuberculosis contacts, endemic fungi).

Medication history: Proton pump inhibitors increase pneumonia risk, corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants affect pathogen spectrum and severity. Vaccination status: Pneumococcal and influenza vaccination history. Previous culture results: Especially important in patients with recurrent pneumonia or chronic lung disease.

Physical Examination Findings

The physical examination in pneumonia should include systematic assessment of vital signs and respiratory system examination:

1. Vital signs assessment:

Temperature, respiratory rate (>30/minute is a CURB-65 criterion), blood pressure (systolic <90 mmHg or diastolic ≤60 mmHg is a CURB-65 criterion), heart rate, and oxygen saturation on room air are critical parameters.

2. Respiratory examination:

Inspection may reveal tachypnea, use of accessory muscles of respiration, cyanosis in severe cases, and decreased chest wall movement on the affected side. Palpation reveals increased tactile fremitus over consolidated areas. Percussion shows dullness over areas of consolidation or pleural effusion, with positive likelihood ratio of 5.7. Auscultation typically reveals crackles (most common finding), bronchial breath sounds (positive likelihood ratio 3.3), decreased breath sounds, egophony (E-to-A changes), and wheezes may be present if underlying bronchospasm.

3. General examination should assess for signs of sepsis, confusion (CURB-65 criterion), cyanosis, signs of immunocompromise, and extrapulmonary manifestations suggesting atypical pathogens.

Laboratory Investigations

Complete blood count (CBC):

Leukocytosis (WBC >11,000/μL) with left shift suggests bacterial infection. Leukopenia (WBC <4,000/μL) may indicate severe infection or atypical pathogen. Normal WBC count doesn’t exclude pneumonia, particularly in atypical or viral cases.

Inflammatory markers:

- C-reactive protein (CRP): Elevated CRP (>40 mg/L) has 70% sensitivity and 90% specificity for pneumonia diagnosis. CRP rises within 4-6 hours of infection, doubling every 8 hours, with half-life of 19 hours. Levels >100 mg/L are highly specific for bacterial pneumonia. However, CRP is not specific for pneumonia and can be elevated in other inflammatory conditions.

- Procalcitonin (PCT): PCT is more specific for bacterial infection than CRP. PCT levels >0.25 ng/mL have 83.9% sensitivity and 61.1% specificity for bacterial pneumonia. PCT is significantly higher in typical bacterial pneumonia (median 2.5 ng/mL) compared to viral (0.09 ng/mL) or atypical pneumonia (0.20 ng/mL). PCT has an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.79-0.90 for diagnosing bacterial pneumonia. The 2019 ATS/IDSA guidelines recommend against using PCT to determine need for initial antibacterial therapy in CAP.

- Arterial blood gas (ABG): Indicated in patients with severe pneumonia or respiratory distress to assess oxygenation, ventilation, and acid-base status.

Microbiological investigations:

- Blood cultures: The 2019 guidelines recommend blood cultures for patients with severe CAP and for all patients empirically treated for MRSA or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Blood culture yield in CAP is approximately 5-14%, with Streptococcus pneumoniae being the most common isolate. Positive blood cultures impact management in approximately 10-15% of cases.

- Sputum Gram stain and culture: Recommended for severe CAP and patients with risk factors for resistant pathogens. Only good-quality sputum specimens (>25 neutrophils and <10 epithelial cells per low-power field) should be processed. Sputum culture identifies a causative organism in only 9-15% of CAP patients. Gram stain showing gram-positive diplococci has 60% sensitivity but 97.6% specificity for Streptococcus pneumoniae. The diagnostic yield is low because most patients receive antibiotics before sample collection.

- Legionella and pneumococcal urinary antigen tests: Recommended for severe CAP, especially with epidemiological risk factors. Legionella urinary antigen is sensitive for Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 (accounts for >80% of cases). Pneumococcal urinary antigen has 70-80% sensitivity and >90% specificity.

- Respiratory viral testing: Recommended during influenza season or when influenza is suspected. Rapid influenza testing has moderate sensitivity (50-70%) but high specificity (>90%). Multiplex PCR panels can detect multiple respiratory viruses simultaneously.

Radiological Imaging

1. Chest X-ray (CXR):

Chest radiography is essential for confirming pneumonia diagnosis, as clinical findings alone are insufficient. The presence of a new pulmonary infiltrate is a key diagnostic criterion for pneumonia. However, chest X-ray may be normal in early infection (first 24-48 hours), severely dehydrated patients, or neutropenic patients.

2. Common radiographic patterns:

Lobar consolidation is characteristic of typical bacterial pneumonia, especially pneumococcal pneumonia. Bronchopneumonia pattern shows patchy, multifocal infiltrates, common with Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and gram-negative bacteria. Interstitial pattern with diffuse bilateral infiltrates suggests viral or atypical pneumonia, particularly Mycoplasma or Chlamydia. Cavitation may indicate necrotizing pneumonia, lung abscess, or tuberculosis. Pleural effusion occurs in 10-40% of bacterial pneumonia cases.

3. Chest CT scan:

CT is more sensitive than chest X-ray for detecting pneumonia, with sensitivity approaching 97%. Indications for chest CT include normal or equivocal chest X-ray with high clinical suspicion, evaluation of complications (empyema, abscess), differentiating pneumonia from other conditions (pulmonary embolism, malignancy), and immunocompromised patients with suspected pneumonia. CT findings include ground-glass opacities, consolidation, tree-in-bud pattern, and associated lymphadenopathy. However, CT-only pneumonia (infiltrate visible on CT but not on chest X-ray) may represent a more benign disease with better prognosis.

Severity Assessment: CURB-65 and PSI Scores

Determining pneumonia severity is crucial for deciding appropriate treatment setting (outpatient vs inpatient vs ICU) and predicting mortality risk.

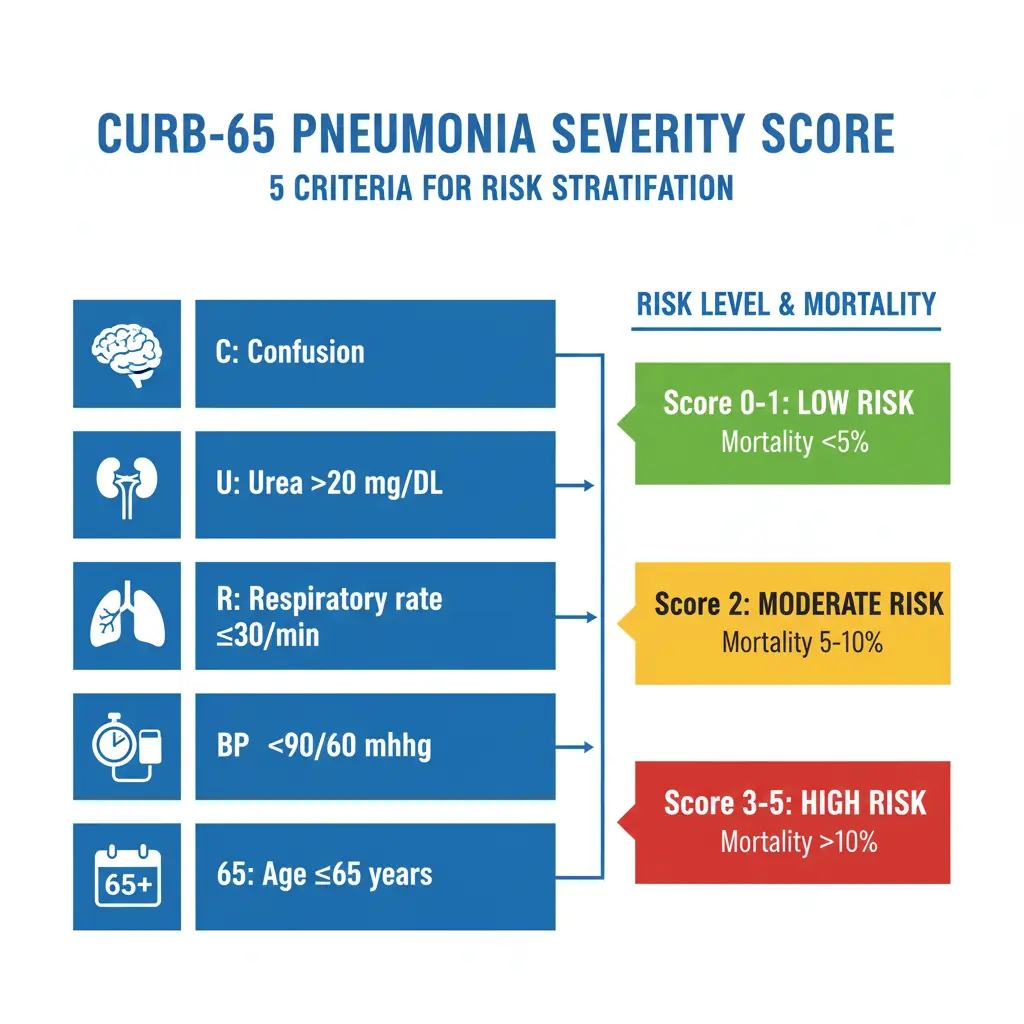

CURB-65 Score

The CURB-65 score is a simple, validated tool for assessing community-acquired pneumonia severity. It assigns one point for each of the following criteria:

C – Confusion: New-onset disorientation to person, place, or time

U – Urea: Blood urea nitrogen (BUN) >20 mg/dL (>7 mmol/L)

R – Respiratory rate: ≥30 breaths per minute

B – Blood pressure: Systolic BP <90 mmHg or diastolic BP ≤60 mmHg

65 – Age: ≥65 years

Score interpretation and management recommendations:

| CURB-65 Score | 30-Day Mortality Risk | Management Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 0-1 | 0.6-2.7% (Low) | Outpatient treatment |

| 2 | 6.8-9.2% (Intermediate) | Consider hospitalization; hospital-supervised treatment |

| 3 | 14.0% (High) | Hospital admission; consider ICU if score = 3 with additional risk factors |

| 4-5 | 27.8% (Very high) | Hospital admission; assess for ICU admission |

Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI)

The Pneumonia Severity Index (also called PORT score) is a more comprehensive tool using 20 variables to stratify patients into five risk classes (I-V). While more accurate than CURB-65, its complexity limits bedside use.

The 2019 ATS/IDSA guidelines recommend using a validated clinical prediction rule, preferentially the PSI (strong recommendation, moderate quality evidence) over CURB-65 (conditional recommendation, low quality evidence) to determine need for hospitalization. However, CURB-65’s simplicity makes it more practical for clinical use.

Additional severity indicators suggesting ICU admission:

Major criteria (one required): septic shock requiring vasopressors, or respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

Minor criteria (three or more required): respiratory rate ≥30/min, PaO2/FiO2 ratio ≤250, multilobar infiltrates, confusion/disorientation, uremia (BUN ≥20 mg/dL), leukopenia (WBC <4,000/μL), thrombocytopenia (platelets <100,000/μL), hypothermia (core temperature <36°C), or hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation.

Causative Organisms: Bacterial, Viral, and Fungal Pathogens

Bacterial Pathogens

Typical bacteria:

- Streptococcus pneumoniae remains the most common cause of CAP globally, accounting for 20-30% of cases. Pneumococcal pneumonia typically presents with acute onset, high fever, rust-colored sputum, and lobar consolidation on imaging. Penicillin resistance is increasing, with up to 30-35% showing some degree of resistance in certain regions.

- Haemophilus influenzae is the second most common bacterial pathogen, particularly in patients with COPD or smoking history. It typically causes bronchopneumonia pattern on imaging.

- Staphylococcus aureus causes severe pneumonia, often following influenza infection or in injection drug users. MRSA pneumonia is associated with necrotizing pneumonia, cavitation, and high mortality (20-40%).

- Moraxella catarrhalis primarily affects patients with underlying lung disease.

Atypical bacteria:

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae is the most common atypical pathogen, accounting for 10-40% of CAP cases. It predominantly affects younger adults (age 5-40 years). Clinical features include gradual onset, non-productive cough, extrapulmonary manifestations (headache, myalgia), and bullous myringitis. Chest X-ray often shows bilateral interstitial infiltrates.

- Legionella pneumophila causes 2-15% of CAP cases but accounts for a higher proportion of severe pneumonia requiring ICU admission. Risk factors include recent travel, exposure to contaminated water sources, smoking, and immunosuppression. Clinical features include high fever, confusion, diarrhea, hyponatremia, and elevated liver enzymes. Mortality rate is 10-15%, higher in severe cases.

- Chlamydia pneumoniae causes 5-10% of CAP cases, typically presenting with pharyngitis, hoarseness, and mild pneumonia.Gram-negative bacteria:Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and other gram-negative bacilli are more common in hospital-acquired pneumonia, patients with chronic lung disease, and those with recent antibiotic exposure.

Viral Pathogens

Respiratory viruses account for 15-30% of CAP cases in adults:

Influenza viruses (A and B) cause seasonal epidemics, with pneumonia occurring as primary viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial superinfection (commonly S. aureus or S. pneumoniae). Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is increasingly recognized in adults, particularly elderly and immunocompromised patients. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) causes viral pneumonia with characteristic bilateral ground-glass opacities on CT imaging. Rhinovirus, adenovirus, and parainfluenza viruses can cause pneumonia, especially in immunocompromised hosts.

Fungal Pathogens

Fungal pneumonia primarily affects immunocompromised patients:

Pneumocystis jirovecii causes pneumonia in patients with HIV/AIDS (CD4 <200 cells/μL) or those on immunosuppressive therapy. Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides immitis, and Blastomyces dermatitidis are endemic fungi in specific geographic regions (Mississippi/Ohio valleys, Southwestern USA, and Upper Midwest/Southeastern USA, respectively). Aspergillus species cause invasive aspergillosis in severely immunocompromised patients, particularly those with prolonged neutropenia.

Differential Diagnosis: Ruling Out Other Conditions

When evaluating a patient with suspected pneumonia, several conditions must be considered in the differential diagnosis:

- Pulmonary tuberculosis: Gradual onset of symptoms over weeks to months, night sweats, weight loss, hemoptysis, and upper lobe cavitary lesions on imaging. Distinguish from acute pneumonia using acid-fast bacilli smear and culture, tuberculin skin test, or interferon-gamma release assay. PCT and CRP levels are typically lower in tuberculosis compared to bacterial pneumonia.

- Acute bronchitis: Cough with or without sputum production but typically no fever, dyspnea, or infiltrate on chest X-ray. Distinguished from pneumonia by absence of radiographic infiltrate.

- Pulmonary embolism: Acute dyspnea, pleuritic chest pain, and hypoxemia but typically no fever or productive cough. D-dimer testing and CT pulmonary angiography help differentiate.

- Congestive heart failure with pulmonary edema: Bilateral infiltrates, dyspnea, orthopnea, elevated jugular venous pressure, and peripheral edema. BNP/NT-proBNP levels are markedly elevated. Responds to diuretic therapy.

- Lung cancer: Chronic cough, weight loss, and persistent infiltrate on imaging. May be complicated by post-obstructive pneumonia. CT and bronchoscopy with biopsy provide diagnosis.

- Interstitial lung diseases: Chronic bilateral interstitial infiltrates, progressive dyspnea, and restrictive pattern on pulmonary function tests. High-resolution CT shows characteristic patterns.

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): Bilateral infiltrates, severe hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2 <300), and absence of cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Pneumonia is a common trigger for ARDS, complicating 7.7-19.7% of mechanically ventilated pneumonia patients.

Management and Treatment Protocols

The management of pneumonia: clinical approach, diagnosis & management for MBBS involves prompt initiation of appropriate antibiotic therapy, supportive care, and monitoring for complications.

Antibiotic Selection Guidelines

The 2019 ATS/IDSA guidelines emphasize early antibiotic administration (within 4 hours of presentation for hospitalized patients) and selection based on severity and risk factors for resistant pathogens.

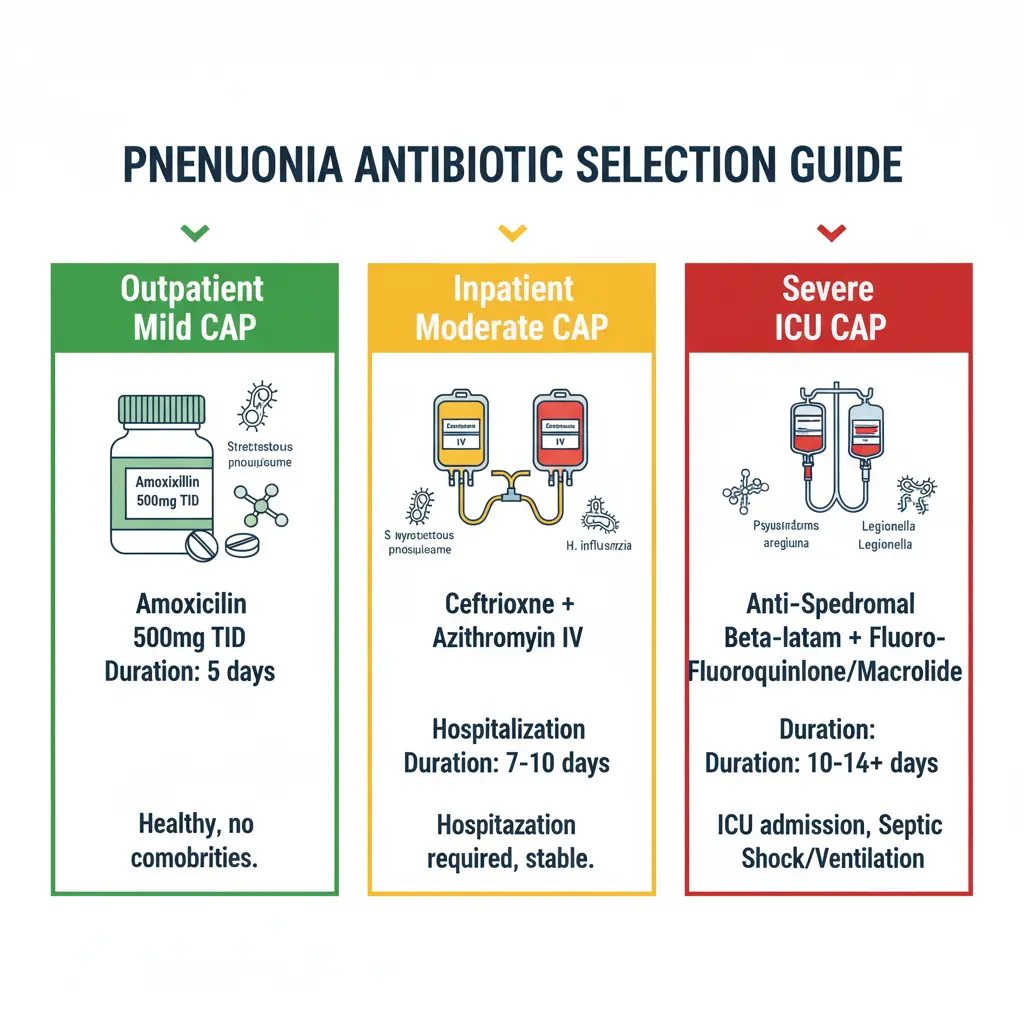

Outpatient Management (CURB-65 0-1):

Previously healthy patients without comorbidities or recent antibiotic use:

- Amoxicillin 1 gram orally three times daily (first-line), OR

- Doxycycline 100 mg orally twice daily, OR

- Macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg on day 1, then 250 mg daily for 4 days OR 500 mg daily for 3 days) only in areas with pneumococcal macrolide resistance <25%

Patients with comorbidities (diabetes, chronic heart/lung/liver/renal disease, alcoholism, malignancy, asplenia) or recent antibiotic use:

- Amoxicillin-clavulanate 875/125 mg orally twice daily OR cefuroxime 500 mg orally twice daily PLUS macrolide, OR

- Respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily OR moxifloxacin 400 mg daily) monotherapy

Inpatient Non-Severe CAP (CURB-65 2, non-ICU):

- Beta-lactam (ampicillin-sulbactam 1.5-3 g IV every 6 hours OR ceftriaxone 1-2 g IV daily OR cefotaxime 1 g IV every 8 hours) PLUS macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg IV/PO daily), OR

- Respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg IV/PO daily OR moxifloxacin 400 mg IV/PO daily) monotherapy

- The 2019 guidelines downgraded macrolide monotherapy from strong to conditional recommendation due to increasing pneumococcal macrolide resistance (>25% in many regions).

Severe CAP (CURB-65 ≥3, ICU admission):

- Beta-lactam (ceftriaxone 2 g IV daily OR cefotaxime 1 g IV every 6-8 hours OR ampicillin-sulbactam 3 g IV every 6 hours) PLUS macrolide (azithromycin 500 mg IV daily) (preferred), OR

- Beta-lactam PLUS respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg IV daily OR moxifloxacin 400 mg IV daily)

- The 2019 guidelines show stronger evidence favoring beta-lactam/macrolide combination over beta-lactam/fluoroquinolone for severe CAP.

Risk factors for MRSA or Pseudomonas aeruginosa:

For patients with prior respiratory isolation of MRSA or documented risk factors:

-

Add vancomycin 15 mg/kg IV every 12 hours OR linezolid 600 mg IV/PO every 12 hours

For patients with prior respiratory isolation of P. aeruginosa or risk factors:

-

Use anti-pseudomonal beta-lactam (piperacillin-tazobactam 4.5 g IV every 6 hours OR cefepime 2 g IV every 8 hours OR meropenem 1 g IV every 8 hours) PLUS anti-pseudomonal fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin 400 mg IV every 8 hours OR levofloxacin 750 mg IV daily)

The 2019 guidelines recommend abandoning the healthcare-associated pneumonia (HCAP) category, emphasizing instead the importance of local epidemiology and validated risk factors for determining empiric coverage needs.

Outpatient vs Inpatient Management

The decision regarding treatment setting should be guided by severity assessment tools (CURB-65 or PSI), clinical judgment, and consideration of social factors:

1. Criteria for outpatient treatment:

CURB-65 score 0-1, PSI class I-II, ability to take oral medications, adequate home support, no hypoxemia (oxygen saturation >90% on room air), and hemodynamic stability.

2. Criteria for hospitalization:

CURB-65 score ≥2, PSI class III-V, severe hypoxemia, hemodynamic instability, inability to maintain oral intake, inadequate home support, or severe comorbidities requiring monitoring.

3. Criteria for ICU admission:

One major criterion (septic shock requiring vasopressors or respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation), or three or more minor criteria as described in the severity assessment section.

Treatment Duration

Standard treatment duration:

Minimum 5 days of antibiotic therapy, provided the patient has been afebrile for 48-72 hours and hemodynamically stable, with improving clinical signs. Most uncomplicated CAP cases require 5-7 days of therapy. Longer durations (7-14 days) may be needed for specific pathogens (Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Legionella) or complicated pneumonia with empyema or abscess formation.

Short-course therapy (3-5 days) with azithromycin has shown equivalent efficacy to longer courses with other antibiotics due to azithromycin’s prolonged tissue half-life and sustained pulmonary concentrations.

Monitoring treatment response:

Clinical improvement should be assessed within 48-72 hours. Lack of improvement warrants re-evaluation for complications, resistant pathogens, alternative diagnoses, or drug-related issues.

Procalcitonin-guided therapy may allow safe reduction in antibiotic duration but is not routinely recommended by current guidelines.

Complications of Pneumonia

Pneumonia can lead to several serious complications that increase morbidity and mortality:

- Pleural effusion and empyema: Parapneumonic pleural effusion occurs in 10-40% of bacterial pneumonia cases. When the fluid becomes infected, it forms empyema, requiring drainage via thoracentesis or chest tube placement. Empyema is associated with prolonged hospitalization and increased mortality.

- Lung abscess: Necrotizing pneumonia with tissue destruction leads to abscess formation, particularly with Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, or anaerobic bacteria in aspiration pneumonia. Treatment requires prolonged antibiotics (4-6 weeks) and sometimes surgical drainage.

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): Severe pneumonia can trigger ARDS, characterized by bilateral infiltrates, severe hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2 <300), and non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema. Pneumonia accounts for approximately 35-65% of ARDS cases. Sepsis is the principal link between pneumonia and ARDS. Mortality rates for ARDS range from 30-40%.

- Sepsis and septic shock: Pneumonia is one of the most common causes of sepsis. Progression to septic shock occurs in approximately 11% of hospitalized CAP patients, with mortality rates exceeding 20-40%. Sepsis-associated ARDS has worse prognosis than ARDS from non-septic causes.

- Cardiovascular complications: Myocardial infarction and cardiac arrhythmias (particularly atrial fibrillation) can be triggered by pneumonia-induced systemic inflammation and hypoxemia. Patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease are at highest risk.

- Renal failure: Acute kidney injury may occur due to sepsis, hypotension, or nephrotoxic antibiotics. Renal dysfunction is an independent predictor of mortality in severe pneumonia.

- Bacteremia: Approximately 5-14% of hospitalized CAP patients have positive blood cultures, most commonly Streptococcus pneumoniae. Bacteremia is associated with increased mortality and longer hospital stays.

- Post-pneumonia complications: Some patients develop organizing pneumonia or bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) as sequelae of acute pneumonia.

Prevention Strategies and Vaccination

Prevention is a cornerstone of reducing pneumonia burden, particularly in high-risk populations:

1. Vaccination

Pneumococcal vaccination:

Two types of pneumococcal vaccines are available: 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) covering 23 pneumococcal serotypes, and 13-valent or 15-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV13, PCV15) or 20-valent (PCV20) covering fewer serotypes but providing stronger immune response.

Current CDC recommendations (2024-2025):

Adults ≥65 years should receive pneumococcal vaccination. Adults 19-64 years with chronic conditions (diabetes, heart disease, lung disease, immunocompromising conditions, smoking, alcoholism) should receive pneumococcal vaccination. Sequential administration of PCV13/PCV15 followed by PPSV23 (after 1 year) or single dose of PCV20 is recommended.

Influenza vaccination:

Annual influenza vaccination is recommended for all individuals ≥6 months of age. Influenza vaccination is particularly important because influenza infection significantly increases the risk of secondary bacterial pneumonia (particularly Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae). Studies show influenza vaccination reduces pneumonia-related hospitalization by 52% and mortality by 70% in elderly populations.

Dual vaccination strategy:

Combined influenza and pneumococcal vaccination provides additive benefits. Meta-analyses demonstrate that dual vaccination reduces pneumonia incidence by 16.5% (relative risk 0.835) and all-cause mortality by 22.9% (relative risk 0.771) compared to influenza vaccination alone. The protective effect is greatest during influenza season and in patients with chronic lung disease.

2. Additional Prevention Measures

- Smoking cessation: Smoking is a major risk factor for pneumonia, increasing risk 2-4 fold. Smoking impairs mucociliary clearance, alters immune function, and damages respiratory epithelium.

- Alcohol moderation: Excessive alcohol use increases pneumonia risk through aspiration, impaired cough reflex, and immune dysfunction.

- Hand hygiene: Proper hand washing reduces transmission of respiratory pathogens.

- Aspiration precautions: For patients with dysphagia or altered consciousness, elevating head of bed, careful feeding techniques, and consideration of modified diet consistency reduce aspiration risk.

- Glycemic control in diabetes: Maintaining HbA1c <7% reduces infection risk in diabetic patients. Poor glycemic control (HbA1c >9%) is associated with increased pneumonia risk and severity.

Common Mistakes to Avoid in Pneumonia Management

MBBS students and junior doctors should be aware of these common pitfalls:

- Delaying antibiotic therapy: Waiting for culture results before starting antibiotics increases mortality. Antibiotics should be initiated within 4 hours of pneumonia diagnosis in hospitalized patients. Early appropriate antibiotic therapy is associated with reduced mortality and shorter hospital stays.

- Inappropriate antibiotic selection: Using only beta-lactam antibiotics without macrolide or fluoroquinolone coverage misses atypical pathogens in 15-40% of cases. Failing to consider risk factors for MRSA or Pseudomonas leads to inappropriate coverage. Over-reliance on macrolide monotherapy in areas with high pneumococcal resistance (>25%) results in treatment failure.

- Inadequate severity assessment: Failing to use validated tools (CURB-65 or PSI) leads to inappropriate disposition decisions. Underestimating severity results in inadequate monitoring and delayed ICU transfer. Discharging high-risk patients (CURB-65 ≥2) without adequate follow-up increases mortality.

- Premature discontinuation of antibiotics: Stopping antibiotics before 5 days (minimum duration) or before clinical stability increases relapse risk. Not ensuring 48-72 hours of afebrile period before discontinuation.

- Failure to reassess non-responders: Not investigating patients who fail to improve within 48-72 hours. Missing complications (empyema, abscess, ARDS) or alternative diagnoses. Not considering resistant pathogens or drug-related issues in treatment failures.

- Over-reliance on physical examination: Diagnosing pneumonia based solely on auscultatory findings without chest X-ray confirmation leads to overdiagnosis. Physical examination has only 47-69% sensitivity for pneumonia diagnosis.

- Ignoring patient risk factors: Not obtaining adequate history of recent healthcare exposure, antibiotic use, or immunocompromising conditions. Missing risk factors for MRSA (S. aureus bacteremia, recent hospitalization) or Pseudomonas (structural lung disease, recent broad-spectrum antibiotics) leads to inadequate empiric coverage.

- Unnecessary testing: Ordering routine sputum cultures in outpatients or non-severe inpatients provides low yield and delays appropriate therapy. Using procalcitonin to determine need for initial antibiotic therapy (not recommended by guidelines).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the difference between typical and atypical pneumonia?

Typical pneumonia is usually caused by bacteria like Streptococcus pneumoniae and presents with acute onset of high fever, productive cough with purulent sputum, and lobar consolidation on chest X-ray. Atypical pneumonia is caused by organisms like Mycoplasma, Legionella, and Chlamydia, presenting with gradual onset, dry cough, prominent extrapulmonary symptoms (headache, myalgia, diarrhea), and bilateral interstitial infiltrates. Atypical pathogens lack cell walls or are intracellular, making them resistant to beta-lactam antibiotics and requiring macrolides, fluoroquinolones, or tetracyclines for treatment.

2. How is community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) different from hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP)?

CAP develops in individuals without recent healthcare exposure (>14 days since hospitalization), is commonly caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae and atypical organisms, and has lower mortality (9.1%). HAP develops ≥48 hours after hospital admission, is more likely caused by multidrug-resistant organisms (MRSA, Pseudomonas), receives inappropriate initial therapy more frequently (28.3% vs 13%), and has higher mortality (24.6%). Treatment approaches differ significantly, with HAP requiring broader-spectrum antibiotics covering resistant pathogens.

3. When should I hospitalize a pneumonia patient?

Use the CURB-65 score to guide hospitalization decisions. Patients with CURB-65 score 0-1 can typically be managed as outpatients. Patients with score 2 should be considered for hospitalization or hospital-supervised treatment. with score ≥3 patients may require hospital admission, with ICU assessment for scores 4-5. Additional factors include inability to take oral medications, hypoxemia (oxygen saturation <90%), hemodynamic instability, inadequate home support, and severe comorbidities.

4. What antibiotics should I prescribe for outpatient pneumonia treatment?

For previously healthy outpatients without comorbidities, prescribe amoxicillin 1 gram orally three times daily (first-line), doxycycline 100 mg twice daily (alternative), or a macrolide (azithromycin) only in areas with pneumococcal resistance <25%. For outpatients with comorbidities (diabetes, COPD, heart disease), prescribe amoxicillin-clavulanate plus macrolide or respiratory fluoroquinolone (levofloxacin 750 mg daily or moxifloxacin 400 mg daily) monotherapy. Always start antibiotics as soon as pneumonia is diagnosed.

5. How long should pneumonia antibiotics be continued?

The recommended minimum duration is 5 days, provided the patient has been afebrile for 48-72 hours, is hemodynamically stable, and shows clinical improvement. Most uncomplicated CAP cases require 5-7 days total. Longer durations (7-14 days) may be needed for specific pathogens (Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas, Legionella) or complicated cases with abscess or empyema. Short-course azithromycin (3-5 days) is effective due to prolonged tissue half-life.

6. What is the CURB-65 score and how do I calculate it?

CURB-65 is a simple tool to assess pneumonia severity and predict 30-day mortality. Award one point for each criterion present: C = new-onset confusion, U = blood urea nitrogen >20 mg/dL, R = respiratory rate ≥30/min, B = systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg or diastolic ≤60 mmHg, 65 = age ≥65 years. Scores 0-1 indicate low risk (outpatient treatment), score 2 indicates intermediate risk (consider hospitalization), and scores 3-5 indicate high risk (hospital admission, consider ICU).

7. Can pneumonia be prevented with vaccines?

Yes, pneumococcal vaccines and influenza vaccines significantly reduce pneumonia risk. Adults ≥65 years and those 19-64 with chronic conditions should receive pneumococcal vaccination (PCV13/PCV15 followed by PPSV23, or single PCV20 dose). Annual influenza vaccination is recommended for everyone ≥6 months. Studies show dual vaccination reduces pneumonia incidence by 16.5% and all-cause mortality by 22.9% compared to influenza vaccine alone. Additionally, smoking cessation, alcohol moderation, and good hand hygiene help prevent pneumonia.

8. What are the most common complications of pneumonia?

Major complications include pleural effusion and empyema (occurring in 10-40% of cases), lung abscess (with necrotizing pneumonia), ARDS (in 7.7-19.7% of mechanically ventilated patients), sepsis and septic shock (11% of hospitalized CAP patients), cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, arrhythmias), acute kidney injury, and bacteremia (5-14% of hospitalized patients). Complications are more common in elderly patients, those with comorbidities, and cases caused by virulent organisms like Staphylococcus aureus or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

9. Why are diabetic patients at higher risk for pneumonia?

Diabetes increases pneumonia risk 2-4 fold due to multiple mechanisms. Hyperglycemia impairs neutrophil chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and bacterial killing. Chronic inflammation in diabetes disrupts both innate and adaptive immunity. Vascular complications narrow pulmonary capillaries and impair lung function. Poor glycemic control (HbA1c >9%) significantly increases pneumonia risk. Diabetic patients also have higher rates of hospitalization and mortality from pneumonia compared to non-diabetics. The CDC recommends pneumococcal and influenza vaccination for all diabetic patients.

10. When should I order a chest CT scan instead of chest X-ray for pneumonia?

Chest CT is indicated when: chest X-ray is normal or equivocal but clinical suspicion remains high, evaluating suspected complications (empyema, abscess, ARDS), differentiating pneumonia from other conditions (pulmonary embolism, malignancy, interstitial lung disease), or assessing immunocompromised patients with suspected pneumonia. CT has 97% sensitivity for detecting pneumonia compared to 60-70% for chest X-ray. However, CT-only pneumonia (infiltrate visible on CT but not chest X-ray) may represent milder disease with better prognosis. Standard chest X-ray remains the first-line imaging modality for suspected pneumonia.

Exam Questions and Answers: University Pattern

Question 1: Long Answer Question (10 Marks)

Q: A 68-year-old male with type 2 diabetes presents to the emergency department with 3-day history of fever, productive cough with yellowish sputum, and shortness of breath. On examination: temperature 39.2°C, respiratory rate 32/min, blood pressure 110/70 mmHg, heart rate 110/min, oxygen saturation 88% on room air. Chest examination reveals dullness to percussion and bronchial breathing in the right lower zone.

- a) What is your provisional diagnosis? (1 mark)

- b) Calculate the CURB-65 score for this patient. (2 marks)

- c) Outline your diagnostic workup. (3 marks)

- d) What would be your initial management including antibiotic therapy? (4 marks)

Model Answer:

a) Provisional diagnosis: (1 mark)

Right lower lobe community-acquired pneumonia with respiratory compromise in a diabetic patient.

b) CURB-65 score calculation: (2 marks)

- C (Confusion): No – 0 points

- U (Urea): Need lab value (assume elevated in diabetic with severe infection) – likely 1 point

- R (Respiratory rate ≥30/min): Yes (32/min) – 1 point

- B (Blood pressure <90/60): No – 0 points

- 65 (Age ≥65): Yes (68 years) – 1 point

Total CURB-65 score: 3 (assuming elevated urea) = High risk, requires hospital admission with consideration for ICU

c) Diagnostic workup: (3 marks)

-

Laboratory investigations:

-

Complete blood count with differential

-

Serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine

-

C-reactive protein and procalcitonin

-

Arterial blood gas analysis (given hypoxemia)

-

Blood cultures (two sets) before antibiotic administration

-

-

Microbiological tests:

-

Sputum Gram stain and culture (good quality specimen)

-

Pneumococcal and Legionella urinary antigen tests

-

Respiratory viral panel if indicated

-

-

Imaging:

-

Chest X-ray (PA and lateral views) – essential for diagnosis confirmation

-

Consider chest CT if X-ray equivocal or to assess complications

-

d) Initial management: (4 marks)

Immediate management:

- Oxygen therapy to maintain SpO2 >90% (target 92-96% in diabetic patient)

- Intravenous fluid resuscitation if needed

- Monitor vital signs closely

- Hospital admission to medical ward or ICU based on clinical response

Antibiotic therapy:

Given severe CAP (CURB-65 score 3) with diabetes as comorbidity:

- First-line: Ceftriaxone 2g IV once daily PLUS Azithromycin 500mg IV once daily

- Alternative: Ceftriaxone 2g IV once daily PLUS Levofloxacin 750mg IV once daily

- Duration: Minimum 5 days, continue until afebrile for 48-72 hours with clinical stability

Supportive care:

- Glycemic control (target glucose 140-180 mg/dL in acute illness)

- Thromboprophylaxis (if hospitalized and not contraindicated)

- Nutritional support

- Respiratory physiotherapy when stable

Monitoring:

- Reassess at 48-72 hours for clinical response

- Switch to oral antibiotics when clinically improving and able to take orally

- Check for complications if not improving

Quick Diagram Prompt for Illustration:

Viva Tips:

- Always mention antibiotic administration within 4 hours for hospitalized patients

- Emphasize importance of blood cultures before antibiotics in severe CAP

- Discuss antibiotic de-escalation based on culture results

- Be prepared to discuss alternative antibiotics for penicillin-allergic patients

- Mention criteria for ICU admission (major and minor criteria)

- Discuss when to consider coverage for MRSA or Pseudomonas

Last-Minute Checklist:

- ✓ CURB-65 components: Confusion, Urea >20 mg/dL, Respiratory rate ≥30/min, Blood pressure <90/60, Age ≥65

✓ Severe CAP antibiotics: Beta-lactam + Macrolide (preferred) or Beta-lactam + Fluoroquinolone

✓ Minimum antibiotic duration: 5 days + afebrile 48-72 hours

✓ Chest X-ray essential for diagnosis confirmation

✓ Blood cultures indicated in severe CAP before antibiotics

✓ Diabetes increases pneumonia risk 2-4 fold

✓ ICU criteria: 1 major (shock/intubation) OR 3+ minor criteria

✓ Common organisms in CAP: S. pneumoniae > H. influenzae > Atypicals

Q: Differentiate between typical and atypical pneumonia based on clinical presentation, causative organisms, and treatment approaches.

Model Answer: (5 marks)

| Feature | Typical Pneumonia | Atypical Pneumonia |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Acute (hours to days) | Gradual (days to weeks) |

| Fever | High-grade (>39°C) with rigors | Low-grade, gradual |

| Cough | Productive with purulent/rusty sputum | Dry, non-productive |

| Chest X-ray | Lobar consolidation | Bilateral interstitial infiltrates |

| Extrapulmonary symptoms | Minimal | Prominent (headache, myalgia, diarrhea, rash) |

| Common organisms | S. pneumoniae, H. influenzae, S. aureus | Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Legionella, Chlamydia pneumoniae |

| Treatment | Beta-lactams (penicillin, cephalosporins) | Macrolides, fluoroquinolones, tetracyclines |

| Why treatment differs | Organisms have cell walls susceptible to beta-lactams | Organisms lack cell walls or are intracellular, requiring antibiotics with intracellular penetration |

- Atypical pneumonia often called “walking pneumonia” due to milder symptoms allowing continued activity

- Mixed infections can occur, hence combination therapy (beta-lactam + macrolide) often used in hospitalized patients

- Legionella can cause severe atypical pneumonia with high mortality, associated with confusion, diarrhea, and hyponatremia

Question 3: Very Short Answer (2 Marks Each)

Q1: List four risk factors for developing pneumonia.

Answer:

- Age >65 years or <2 years

- Chronic diseases (COPD, diabetes, heart disease, chronic kidney disease)

- Immunocompromised states (HIV, malignancy, immunosuppressive therapy)

- Smoking and alcohol abuse

(Additional: aspiration risk, recent hospitalization, poor nutritional status)

Q2: What is the significance of procalcitonin in pneumonia diagnosis?

Answer:

- Procalcitonin (PCT) is more specific for bacterial infection than CRP

- PCT >0.25 ng/mL suggests bacterial pneumonia (83.9% sensitivity, 61.1% specificity)

- PCT significantly higher in typical bacterial pneumonia (median 2.5 ng/mL) vs viral (0.09 ng/mL) or atypical pneumonia (0.20 ng/mL)

- However, 2019 ATS/IDSA guidelines recommend against using PCT to determine need for initial antibiotic therapy

- PCT may guide antibiotic duration but not routinely recommended

Q3: Name three complications of severe pneumonia.

Answer:

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS)

- Pleural effusion and empyema

- Sepsis and septic shock

(Additional: lung abscess, acute kidney injury, cardiovascular complications)

Conclusion

Understanding pneumonia: clinical approach, diagnosis & management for MBBS is fundamental to your success as a medical student and future physician. This comprehensive guide has covered everything from the basic pathophysiology and clinical presentation to advanced diagnostic approaches, evidence-based treatment protocols, and exam-oriented content tailored specifically for MBBS students and healthcare professionals.

Key takeaways to remember:

Pneumonia remains a leading cause of infectious disease mortality worldwide, affecting vulnerable populations including the elderly, diabetic patients, and immunocompromised individuals. Early recognition using clinical assessment combined with chest imaging is crucial for prompt diagnosis and treatment initiation. The CURB-65 score provides a simple, validated tool for severity assessment and disposition decisions, with scores ≥3 requiring hospital admission. Appropriate antibiotic selection based on severity and risk factors for resistant pathogens is essential, with antibiotics ideally administered within 4 hours for hospitalized patients. The distinction between typical and atypical pneumonia guides antibiotic choice, with atypical organisms requiring macrolides, fluoroquinolones, or tetracyclines rather than beta-lactams.

Vaccination strategies, particularly pneumococcal and influenza vaccines, significantly reduce pneumonia incidence and mortality, especially in high-risk populations. Regular reassessment of treatment response at 48-72 hours is critical to identify treatment failures, complications, or alternative diagnoses. Understanding these principles will not only help you excel in your MBBS exams but also prepare you to provide evidence-based, high-quality care to pneumonia patients throughout your medical career.

Are you an MBBS student or medical professional looking to stay updated with the latest clinical approaches and evidence-based medicine?

Subscribe to the Simply MBBS newsletter to receive:

- Weekly updates on important medical topics with exam-oriented content

- Clinical case discussions and diagnostic pearls

- Latest guideline updates and research summaries

- Exclusive study materials and quick reference guides

- Tips for NEET-PG and USMLE preparation

- Visit simplymbbs.com to explore more comprehensive articles on medicine, surgery, pediatrics, and other specialties—all written by medical experts for medical students and curious readers.

Join our community of over thousands of medical students and professionals who trust Simply MBBS for clear, evidence-based medical education!

Don’t let complex medical topics overwhelm you—we break down everything into simple, understandable content while maintaining clinical accuracy. Subscribe today and take your medical knowledge to the next level!